In 2010, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued guidance that requires companies to tell shareholders how they may be harmed by proposed energy regulations, unless the company determines that the regulation will be unlikely to affect the company.[1] Since then, shareholder groups, environmental organizations, and proxy advisory firms have complained that companies are ignoring or skirting this requirement.[2] And this criticism has only grown louder as the Obama administration has adopted new greenhouse gas emission standards that apply to a wide range of old and new power plants, refineries, and factories.

But in another forum, companies have been very open about the risks posed by regulation: corporate comments to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on proposed regulations. In a new paper, titled “How Cheap is Corporate Talk?”, I compare corporate comments to regulators with what they tell their investors.

The paper examines corporate predictions about the EPA’s Renewable Fuel Standard. The Renewable Fuel Standard forces oil companies to blend renewable fuels such as ethanol into the motor fuels that they sell, and the EPA sets a required percentage each year. So oil companies have to sell less of their own product and must purchase ethanol and other renewable fuels. This paper matches oil companies’ annual comments to the EPA with contemporaneous Form 10-K securities disclosures from the same companies.

The study finds that oil companies made significantly more predictions about how the Renewable Fuel Standard would harm them in comments than they disclosed in their 10-K statements. For example, one oil company told the EPA that if the Renewable Fuel Standard wasn’t changed, it would “limit the supply of gasoline and diesel fuel” and cause “severe economic harm.” In its securities disclosure, the only thing its parent company told its investors was that rules like the Renewable Fuel Standard were creating a strong market for biofuels. And it even implied that that was a good thing because it had a side business as a biofuel producer.

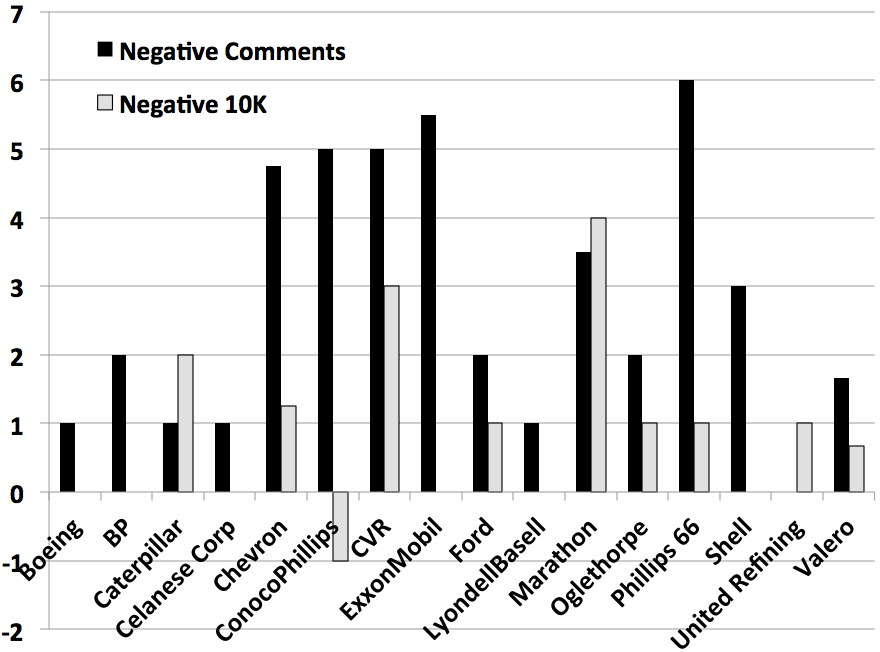

On average, companies that oppose the Renewable Fuel Standard told EPA approximately three ways that the Renewable Fuel Standard would harm them in each year’s comments. Companies most often said it was infeasible to comply with the standard and that it would raise their cost of production. In contemporaneous securities disclosures, companies disclosed less than one way that the Renewable Fuel Standard might harm them. And some of the same companies that told the EPA its rules were infeasible even bragged to investors that they were not only set to comply with current requirements, but also well positioned to meet the Standard’s increasingly ambitious future goals.

Average negative impacts identified by companies in comments and securities disclosures filed from 2010-2013

Despite this inconsistency, it’s possible that companies are giving investors their fair assessment of regulatory risk; perhaps only their comments to EPA are exaggerated. After all, there is no penalty for deceiving regulators, but misleading investors could subject companies to liability under SEC Rule 10b-5. If the only problem is that companies are misleading regulators, the article has a solution: EPA should ask companies to file excerpts from their securities disclosures along with their comments to show they take their own warnings seriously enough to share them with their investors.

But the stark warnings to EPA also support investor groups that say companies are not being forthcoming with their investors about regulatory risk. These investors should use company comments to identify risks that companies may be minimizing in their 10-K disclosures. And the SEC should insist that companies tell investors about any risks that they are stressing to regulators. Perhaps companies would respond to this pressure by toning down their comments rather than identifying more risks in their securities disclosures. But even then the SEC’s efforts would not be wasted: EPA would receive more reliable, less exaggerated, information.

In the meantime, corporate counsel should get ahead of regulators and investors by aligning comments and securities disclosures. When a company’s comments and 10-K disclosures are revealed to be inconsistent, it has put itself in a lose-lose situation. Regulators will discount the company’s pessimistic comments. But if a new rule does harm the company, investors will have evidence to support a Rule 10b-5 lawsuit. Although it is harder to sue a company for “soft” information or predictions about the future, in this case company comments would support an inference that the company did not even believe its own assurances.[3] And few companies would relish the prospect of having to prove in court that their dire warnings to EPA were entirely insincere.

Proactive companies could even bolster their credibility by voluntarily filing excerpts from their securities disclosures along with their comments. If they did so, regulators might be more inclined to take their concerns seriously in crafting final rules. Thus, aligning corporate comments with corporate securities disclosures would protect companies from liability, enhance industry’s credibility in notice-and-comment rulemaking, and improve the information available to regulators.

ENDNOTES

[1] Commission Guidance Regarding Disclosure Related to Climate Change; Final Rule, 75 Fed. Reg. 6,290, 6,296 (Feb. 8, 2010).

[2] See Jim Coburn & Jackie Cook, Ceres, Cool Response: The SEC & Corporate Climate Change Reporting 5 (Feb. 2014); New ISS Corporate Services Report Highlights Need for Improved Company Disclosure Per New SEC Climate Risk Disclosure Guidelines,Press Release, ISS Corporate Services (Oct. 12, 2010) http://www.isscorporatesolutions.com/node/140.

[3] See Omnicare, Inc., et al. v. Laborers Dist. Council Constr. Ind. Pension Fund et al., 575 U.S. _ (2015) (slip op. at 6-9).

The preceding post comes to us from James Coleman (@energylawprof), Assistant Professor at the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Law and Haskayne School of Business. It is based on his article titled “How Cheap is Corporate Talk?”, which is available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog