Four years ago, the SEC set out to improve its cost-benefit approach in rulemaking. After enduring a series of judicial setbacks (e.g., Business Roundtable v. SEC) and criticisms from the Members of the Senate Banking Committee, the SEC conducted an introspective review to identify weaknesses and inconsistencies in its economic analysis process. This assessment resulted in the March 2012 publication of a memorandum (hereafter, the ‘New Guidance’) that formulates how the SEC would conduct cost-benefit analysis moving forward.[1]

The New Guidance mandates that every SEC economic analysis must include: (i) a stated need for rulemaking; (ii) a well-defined economic baseline of the status quo; (iii) identification of alternative regulatory approaches; and (iv) an analysis of the economic consequences (i.e., the costs and benefits) of the proposed action and each alternative as compared to the baseline.

In my article, The Evolving Role of Economic Analysis in SEC Rulemaking, I consider the consequences of these events on both the SEC’s economics division and on its economic analysis. I also contend that the economic baseline can be as important as the estimation of the costs and benefits of a proposed rulemaking activity.

Organizational Changes

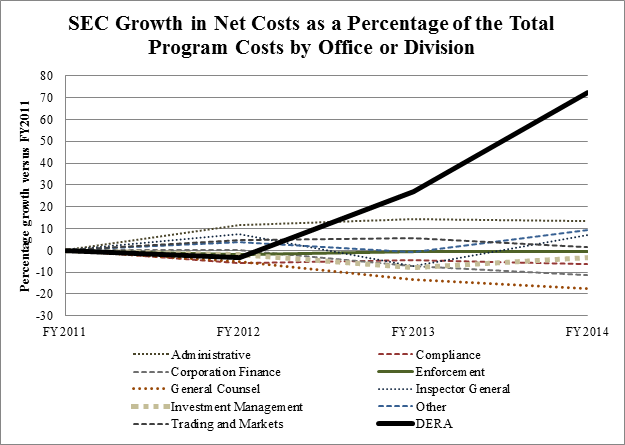

In the period following the New Guidance, a number of discernable changes took place within the SEC’s Division of Economic and Risk Analysis (DERA). DERA’s net program costs as percent of the SEC’s total budget grew by 72% between FY2011 and FY2014, which is five times greater than the proportional growth in any other SEC office or division during this period (see Figure 1). In the Congressional budget justification, the SEC directly attributes this growth in resource allocation to hiring financial economists to conduct economic analysis in support of rulemaking. Since 2011, the number of specialized offices within DERA also expanded and its staff of Ph.D. financial economists more than doubled in size from approximately 30 in 2011 to well over 60 in 2015. Empirically, it is clear that the SEC committed significantly greater resources towards its economic division following the New Guidance.

Economic Analysis

To illustrate the effect of these changes on the SEC’s cost-benefit analyses, I consider a case study of the proposed and final rule on risk retention in residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) under the Dodd-Frank Act, which encompasses the periods before and after the New Guidance.

Academic literature points to the growth of private-label RMBS as one of the principal causes of the financial crisis. The loans underlying these securitizations were characterized by non-traditional mortgage products and underwriting practices that resulted in the transfer of layers of risk to investors. Because the compensation of securitization agents was not necessarily tied to the performance of the loans underlying the RMBS, this gave rise to moral hazard that was ultimately blamed for the mortgage crisis. In Dodd-Frank, Congress attempts to align the incentives of securitization agents by requiring risk retention or “skin in the game.”

Section 941 of Dodd-Frank tasks the SEC and other joint regulators with prescribing rules requiring at least five percent risk retention for asset-backed securitizations. However, a contentious exemption was to be determined by how the joint regulators would define a Qualified Residential Mortgage or QRM. Under Dodd-Frank, securitizations of loans meeting the definition of a QRM are exempt from all risk retention. Congress instructed regulators to define a QRM based on analysis of the relationship between certain loan or borrower characteristics and historical mortgage performance. The notion was that some loans had sufficiently low default probability such that costly risk retention was unnecessary.

Following the proposed risk retention rules in 2011, housing market participants criticized the economic analysis accompanying the proposed definition of a QRM. Comment letters claimed that the SEC and other joint regulators used the wrong dataset for analysis of historical loan performance and did not conduct a robust multivariate analysis. Moreover, there was a push to loosen the QRM definition by aligning it with the definition of a Qualified Mortgage (QM) as defined by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in January 2013. Some argued that loans meeting the looser QM definition performed well enough and that a more restrictive QRM definition would impede the housing market recovery and disproportionately limit access to mortgages for low-income and minority borrowers.

In response to these concerns, and in accordance with the New Guidance, the SEC conducted an expanded analysis of the factors associated with default in private-label RMBS. The SEC published this analysis on its website as a DERA White Paper[2] and referenced it along with other joint regulators in the 2013 risk retention re-proposal and the 2014 final rule. The DERA White Paper responds directly to the concerns of commenters by conducting a multivariate analysis focusing on a strict set of private-label RMBS loans. The analysis shows that the factors included in the definition of a QM only slightly reduce historical default rates in their sample from 44% to 34%. Importantly, the SEC finds credit scores and loan-to-value ratios as among the best predictors of default, yet both are absent from the final definition of a QM.

In the final risk retention rule in 2014, the joint regulators chose to adopt the loosest possible definition of a QRM under Dodd-Frank by aligning it with the definition of a QM. Although this seemingly contradicts the conclusions in the DERA White Paper, I contend that the SEC’s expanded analysis as required by the New Guidance provided important information to SEC commissioners and other regulatory principals about the correct economic baseline and the potential effects of each policy choice. As the guidance requires, the SEC clearly articulates the expected default rates under each scenario and responds directly to commenters’ concerns of inadequate or faulty analysis for the purposes of defining a QRM. This sentiment is echoed by SEC Commissioner Luis Aguilar, who noted in voting to adopt the final risk retention rule that he was concerned with deferring to the QM definition as it would exempt loans with risky characteristics identified in the DERA White Paper. However, his decision was informed by the DERA White Paper and by the periodic review of the QRM definition.[3]

Overall, my article underscores the enhanced role of sound economic analysis and economists in aiding SEC commissioners in making well-informed policy choices. The case study also highlights that focusing solely on the SEC’s identification and estimation of costs and benefits under-emphasizes one of the most essential elements of the New Guidance: the economic baseline.

ENDNOTES

[1] See U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission, Current Guidance on Economic Analysis in SEC Rulemakings, (Mar. 16, 2012), available at https://www.sec.gov/divisions/riskfin/rsfi_guidance_econ_analy_secrulemaking.pdf.

[2] See Joshua White & Scott Bauguess, Qualified Residential Mortgage: Background Data Analysis on Credit Risk Retention, DERA White Paper (Aug. 2013), available at https://www.sec.gov/divisions/riskfin/whitepapers/qrm-analysis-08-2013.pdf.

[3] See Commissioner Luis A. Aguilar, Skin in the Game: Aligning the Interests of Sponsors and Investors, (Oct. 22, 2014), available at http://www.sec.gov/News/PublicStmt/Detail/PublicStmt/1370543250034.

The preceding post comes to us from Joshua T. White, Assistant Professor in the Department of Finance, Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia. The post is based on his recent article, which is entitled “The Evolving Role of Economic Analysis in SEC Rulemaking” and available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog