Over the last few years, hedge fund activism has received a great deal of coverage in financial media (and in the mainstream press), has triggered heated debates and been the focus of much academic research. Saviour of capitalism for some, for others, activist hedge funds are but mongers of short-term tactics which eventually damage business corporations[1].

Academic research on the topic mostly focused on the short-term returns surrounding the intervention date, and the few ones that examined the longer-term relationship with performance were often marred by various methodological issues. Coffee and Palia (2014), among others, beseeched researchers on activism for a change of focus: “Future research needs to focus more specifically on where activism causes real changes in firm value and where it does not.”[2] We took on the challenge and explored, among other things, the consequences of activism over time when compared to a random sample of firms with similar characteristics at the time of intervention.

Focusing on activist events of the years 2010 and 2011, we obtained a sample of 290 campaigns initiated by 165 activist hedge funds which targeted 259 distinct firms. To map out the actions and performance of these 259 targeted companies, we have set up a random sample of 259 companies selected to match the targeted companies at the intervention year in terms of industry classification and market value.

This study brings to light a number of facts and some compelling evidence.

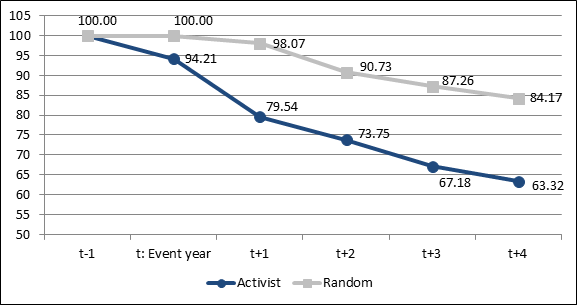

We found that the best way, bar none, for the activists to make money for their funds is to get the company sold off or substantial assets spun-off. No less than 81 targeted companies (or 31%) were sold off, a much larger percentage than occurred in the matched random sample (14%). Figure 1 shows a survival rate for the targeted firms of 63% four years after the intervention, as compared to 84% for the random sample of firms.

FIGURE 1. Survival rate of firms at year end: activist vs. random, base 100 at t-1. The survival rate represents the percentage of firms that were still actively listed at year end (thus excluding firms that were delisted, liquidated of filed for chapter 11, and firms that were either sold or merged).

The evidence is pretty clear that the much vaunted “improvements” in operating performance (ROA, ROE, Tobin’s Q) result mainly from some basic financial manoeuvres (selling assets, cutting capital expenditures, buying back shares, etc.).

However, there is no evidence of deterioration in performance over a three-year period. That is not a result that owes much to the forbearance of activists. Business firms tend to be resilient and their management adaptive to the new reality of activists’ requirements. If the targeted firm can survive the holding period of the activist (more than a third will not), then, and only then, will they be able to start managing again for the longer term.

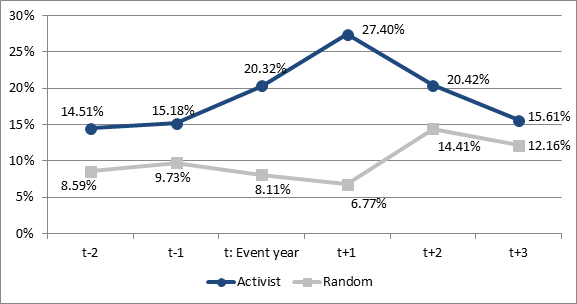

In general, the stock’s performance of targeted companies over a three-year span barely matches the performance of a random sample of companies[3]. But the activist hedge funds, by timing their entry and exit of a stock, by using derivatives and leverage on occasion to enhance their yield, by benefiting from the “control” premium on getting companies sold off, may well achieve highly positive results.

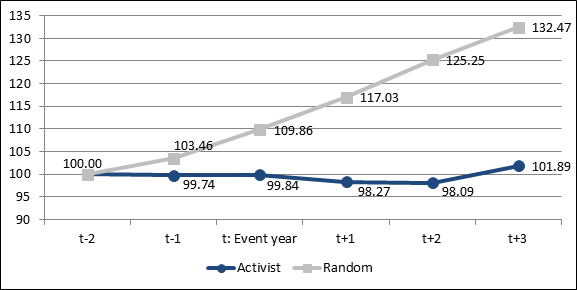

For targeted companies, the most immediate consequence is the likelihood of being sold off. For other targeted companies, this hedge fund episode often results in change of senior management and board members (Figure 2), stagnation of assets (Figure 3) and R&D.

While not lethal over the short period of time that these hedge funds hang around, many companies may come out of the experience as shrunken firms that may have lost a couple of years to their competitors.

The most fundamental issue raised by the phenomenon of hedge fund activism is the crucial assumption that underpins their activities (or at the very least underpins the arguments of their supporters), that is: “Outsiders analyzing financial data from afar can determine that a company is not managed so as to maximize value for its shareholders and that some specific actions they have identified should be taken that would benefit shareholders and would be in the long-term interest of the company.”

Indeed, the argument is made that the cuts in R&D and capital expenditures are applied only to those projects that have no economic justification, that the allocation of cash resources to buy back shares is a better use than some misguided capital investment; of course selling the company (or splitting it up) provides the best outcome for the company and contributes to the overall efficiency of the economic system.

An essential corollary of this “argument” has to be that, in many instances which activists are particularly adept at spotting, management and boards of directors are incompetent, complacent, lack foresight and are unable to act in a manner that serves the best interest of their company. Given the very small size of most companies targeted by hedge funds, that may occur more readily.

But to accept that occurrence as a general rule would be misguided. It would seem a bit unusual that managers, despite their large stock-related compensation, would, with the blessing of their board of directors, waste or misspend R&D funds and capital; until, that is, a wise, better informed activist hedge fund manager comes around to point out the errors of their way.

Either that concept of the business world is accurate, then the whole system of governance of publicly listed businesses must be scrapped and shareholders should call the shot directly and give their marching orders to management; or that view is wrong and management and boards of directors know best what is in the long-term interest of the company. That is a clear choice and one that underpins much of the divergent views on the role and impact of activist hedge funds.

While activist hedge funds (and a number of academics, sheltered by reams of data) have a stake in the first point of view, business people and those whose jobs bring them in close contact with the real world of business tend to partake of the second point of view.

This research does not provide any evidence of the superior strategic sagacity of hedge fund managers but does point to their keen understanding of what moves stock prices in the short term. Indeed, in none of the 259 cases studied here did hedge funds make proposals of a strategic nature to enhance the long-term performance of the firm.

That should concern society, governments, pension funds and other institutional investors with pretension of a long-term investment horizon.

ENDNOTES

[1] See “The case for and against activist hedge funds”, by Yvan Allaire (2015), for a detailed discussion.

[2] See John C. Coffee, Jr., and Darius Palia, “The Impact of Hedge Fund Activism: Evidence and Implications”, ECGI Law Working Paper, No. 266/2014, September 2014, p.82.

[3] We found no statistically significant mean differences between the two groups.

This post comes to us from Yvan Allaire, Ph.D. (MIT) and Executive Chair of the Institute for governance of private and public organizations (IGOPP), and François Dauphin, Chartered Professional Accountant (CPA, CMA), MBA and Director of Research of IGOPP. The post is based on the authors’ forthcoming paper, which is entitled “The game of ‘activist’ hedge funds: Cui bono?” and is available here or here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog