Moody’s, S&P and Fitch represent an oligopoly in the credit rating business, accounting for 94 percent of the global market (Candelon et al., 2014) and for about 96.5 percent of all the outstanding ratings in U.S.[1] The three agencies are key players in financial markets as they assess the credit worthiness of almost any debt issuer including governments, firms, municipalities and financial institutions. Moody’s, S&P and Fitch heavily affect corporate financing through ratings assigned to corporate debt. The economic literature has shown that bond ratings are strongly correlated with private bond yields (Hand et al., 1992; Hite and Warga, 1997) and also to stock returns of debt issuers (Bannier and Hirsh, 2010; Dichev and Piotroski, 2001; Holthausen and Leftwich, 1986). Indeed, besides the issuer’s ability to repay debt, private bond ratings signal future profit opportunities, reliability as a business partner and more in general the value of the firm.

Even after the financial crisis for which credit rating agencies have been blamed, ratings are still largely used as reference for investment decisions. We argue that changes in the financial environment over the last decade may have affected investors’ reliance on ratings by Moody’s, S&P and Fitch.

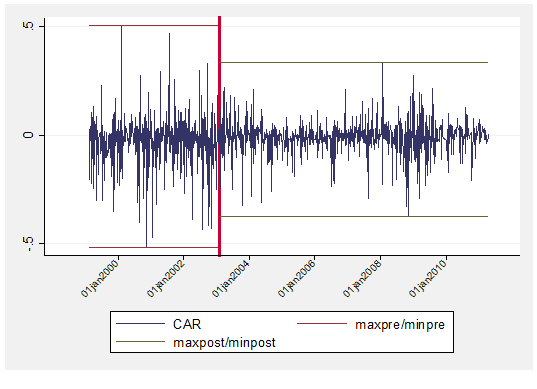

On a sample of 657 firms listed in the U.S. that experienced at least one downgrade from Moody’s, S&P or Fitch between 1999 and 2011, we test how downgrades affect equity abnormal returns using an event study analysis.[2] We find a strong and significant decrease in the stock market response to downgrades at the beginning of 2003 (Figure 1) after the Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) Report on Credit Rating Agencies issued in January 2003. The Report is the outcome of a study mandated to the SEC, in response to the Enron scandal, by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002 in order to assess “the role of credit rating agencies in the evaluation of issuers of securities” and “the importance of that role to investors and the functioning of the securities markets.” [3] The Report represents a turning point for the rating business in U.S. and highlights several potential issues affecting the quality of ratings, such as conflict of interests and low competition. In other words, the Report signals the regulator’s acknowledgment of the need to reform the business. However the Report does not bring any formal change to the market of ratings. Therefore any evidence related to its issue shall not be a consequence of structural changes in the rating regulatory framework. Rather, the Report more likely triggered investors’ skepticism toward Moody’s, S&P and Fitch, increasing awareness of the limits of ratings and leading to the sharp decrease in market response to downgrades.

Figure 1. Cumulative abnormal returns around downgrades from 1999 to 2011. CAR is cumulative abnormal return in the three day-window around the downgrade’s announcement. The vertical line is placed at the end of January 2003 when the SEC’s Report is published. The red line represents maximum (maxpre) and minimum (minpre) CAR before January 2003 and the green line represents maximum (maxpost) and minimum (minpost) CAR after January 2003.

There are three phenomena involving the rating business that are captured by the Report and that may be responsible for the reduction of the stock market reaction to rating changes. First of all, the Report is a clear negative signal sent by the regulator about the reliability of credit rating agencies. Second, it builds on the negative impact that the Enron and WorldCom scandals in 2001 and 2002 had already on credit rating agencies’ reputation as they failed to foresee the companies’ defaults. Third, in response to the Report the credit rating agencies may have updated their methodologies and policies to maintain the status quo and to regain trust (Baghai et al., 2014; Cheng and Neamtiu, 2009). Therefore, the Report may have had an impact on market reaction to downgrades through a change in the behavior of the agencies and/or directly affecting investors’ beliefs. Our hypothesis is that the decrease in correlation between stock returns and downgrades by Moody’s, S&P and Fitch after the Report is due to a reduction in the information content of rating changes relative to the overall informational environment available to investors. Investors, especially institutional ones, have thus greater incentives to anticipate rating changes after the Report and are able to do that through the development of the CDS market and the greater diffusion of other financial information.

The growth of the market for CDSs per se may be an explanation of the decrease in market reaction to downgrades that we find. We do not deny this possibility; rather we identify it as a channel through which investors anticipate/substitute rating changes. However, in our paper we show that the decrease in market reaction to downgrades that we find cannot be entirely explained by the increase in CDSs. Indeed, although the proxy for the diffusion of CDSs that we borrow from Chava et al. (2015) is positively correlated with CARs (that is, the increase in the proportion of CDSs corresponds to a decrease in the absolute value of CARs around downgrades), the stock market response to downgrades displays a shift toward zero in 2003 that is not explained by the growing trend in CDSs.

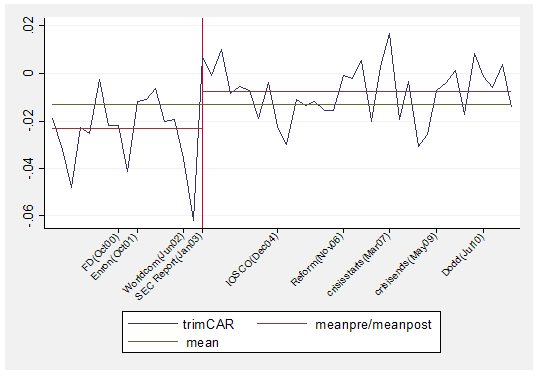

Alternative explanations for the decrease in the stock market reaction to downgrades after the Report such as a reduction in risk aversion over time which leads to lower reaction to negative news, or a change in the magnitude of rating changes or the increased use of watch lists, are not supported by our empirical results. Given the length of the period under analysis, we also account for other events that may have affected market reaction to rating changes before and after the SEC’s Report (Figure 2). The most relevant being the Credit Rating Agencies Reform Act of 2006 approved with the aim to improve the quality of ratings by increasing competition and transparency. We show that the Reform does not drive any of the results we find.

Figure 2 Three months average of cumulative abnormal returns around downgrades from 1999 to 2011. TrimCAR is the average over three months of cumulative abnormal returns in the three day-window around the downgrade’s announcement. Several events regarding the rating business are signaled on the on the x-axis. The green line is the average CAR on the whole sample. The vertical line is placed at the end of January 2003 when the SEC’s Report is published. The red line represents the average CAR observed before January 2003 and the average CAR observed after January 2003.

Summarizing, we find empirical evidence of a reduction in abnormal stock returns associated to downgrades issued by Moody’s, S&P and Fitch, in the short run after the SEC’s Report of January 2003. As long as equity abnormal returns measure the information content of ratings, our hypothesis is that the reduction in excess returns that we find after 2003 can be explained by the fact that investors perceive the information conveyed by downgrades as relatively less relevant to their investment decisions with respect to the overall informational environment. The Report is the result of strong criticisms to Moody’s, S&P and Fitch’s behavior especially with the Enron and the WorldCom scandals, and it spurred enough debate and attention on the three rating agencies to negatively affect investors’ perception of the informative value of ratings. This lead to increasing resort to alternative information that was becoming more available in that period due to the widening of information disclosure imposed on corporate entities and equity analysts by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the development of new financial products (such as stock options and CDS) and the general increase of financial information sources due to the development of web based information providers.

Concluding, we think that ratings are still so widely demanded not because of the unique information they convey, but because they possess the value of an easy at hand certification of credit quality. Although investors have reduced their reliance on ratings and the Dodd Frank Act required every Federal Agency to remove any reference to ratings from regulations, they are still widely used in private contracting and as governance tools to solve principal-agent conflicts. Thus, in our opinion ratings still play a relevant role because issuers in need of certification have incentives to demand them (Sufi 2009; Kisgen and Strahan, 2010) and because their use has become an established practice. Survey data confirm our findings, among others the Duff and Eining (2007) survey reports that 54 percent of interviewed investors indicate that rating “[…] was just one input of many”. Even more significantly, the survey by Cantor et al. (2007) highlights that herding behavior is as relevant a motivation for the use of ratings by fund managers and plan sponsors as is the belief that the informational content of ratings is good for making sound investment decisions.

REFERENCES

Baghai, R. P., Servaes, H., Tamayo, A. (2014). Have rating agencies become more conservative? Implications for capital structure and debt pricing. The Journal of Finance 69(5), 1961-2005.

Bannier, C.E., Hirsch, C.W., 2010. The economic function of credit rating agencies: What does the watch list tell us? Journal of Banking & Finance 34, 3037-3049.

Candelon, B., Gautier, A. Petit, N., 2014. Market Power in the Credit Rating Industry: State of Play and Proposal for Reforms. CPI Antitrust Chronicle, January 2014 (2).

Cantor, R., Gwilym, O.A., Thomas, S.H., 2007. The use of credit ratings in investment management in US and Europe. The Journal of Fixed Income 17(2), 13-26.

Chava, Sudheer and Ganduri, Rohan and Ornthanalai, Chayawat, Are Credit Ratings Still Relevant? (April 5, 2015). EFA 2012, Copenhagen, 15-18 August 2012. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2023998 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2023998

Cheng, M., Neamtiu, M., 2009. An empirical analysis of changes in credit rating properties: Timeliness, accuracy and volatility. Journal of Accounting and Economics 47, 108-130.

Dichev, I.D., Piotroski, J.D., 2001. The long-run stock returns following bond ratings changes. The Journal of Finance 56, 173-204.

Duff, A., Eining, S., 2007. Credit Rating Agencies: Meeting the Needs of the Market? The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Goh, J.C., Ederington, L.H., 1993. Is a bond rating downgrade bad news, good news, or no news for stockholders? The Journal of Finance 48, 2001-2008.

Hand, J.R.M., Holthausen, R.W., Leftwich, R.W., 1992. The effect of bond rating agency announcements on bond and stock prices. The Journal of Finance 47, 773-752.

Hite, G., Warga, A., 1997. The effect of bond-rating changes on bond price performance. Financial Analysts Journal 53, 35-51.

Holthausen, R.W., Leftwich, R.W., 1986. The effect of bond rating changes on common stock prices. Journal of Financial Economics 17, 57-89.

Kisgen, D. J., Strahan, P. E., 2010. Do regulations based on credit ratings affect a firm’s cost of capital?. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 4324-4347.

Sufi, A. (2009). The real effects of debt certification: Evidence from the introduction of bank loan ratings. Review of Financial Studies, 22(4), 1659-1691.

ENDNOTES

[1] Annual Report (December, 2013) on Nationally Recognized Credit Rating Agencies of the Security and Exchange Commission to Congress under Section 6 of the Credit Rating Agency Reform Act of 2006.

[2] Abnormal returns are returns in excess of some measure of the expected return after compensating for risk. We use different models to measure abnormal returns.

[3] Pub.L. 107–204, 116 Stat. 745, enacted July 30, 2002. Title VII. Studies and Reports. Sec. 702. Commission study and report regarding credit rating agencies. pp. 798-799.

The preceding post comes to us from Ginevra Marandola and Rossella Mossucca, post-doctoral fellows in the Department of Economics, University of Bologna and Einaudi Institute of Economics and Finance of Rome, respectively. The post is based on their paper, which is entitled “When Did the Stock Market Start to React Less to Downgrades by Moody’s, S&P and Fitch?” and available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog