The debate over board leadership does not seem to go away especially in the U.S. where market participants have long agreed on the need for greater independence in principle, while largely disagreeing on the measures required to put it into practice. Some feel strongly that an independent Chair is absolutely essential, while others believe that an appropriately empowered independent Lead Director can also provide sufficient independent leadership.

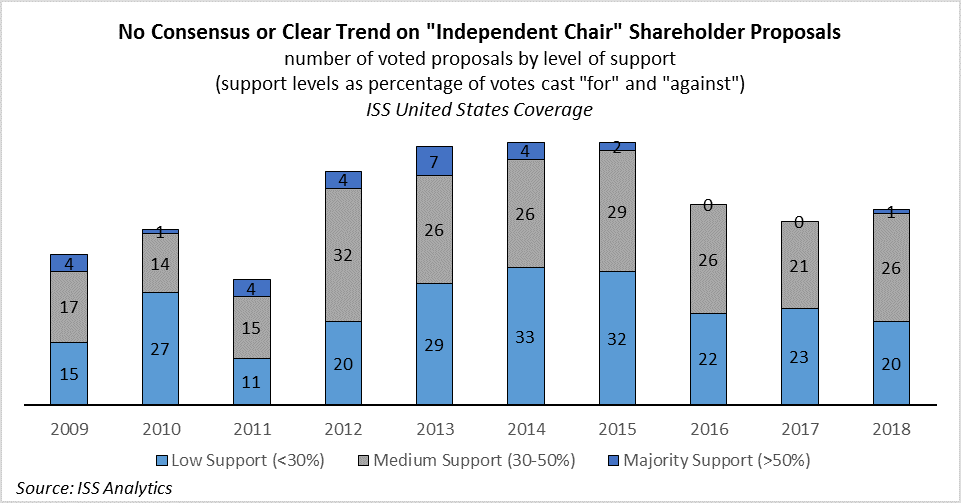

Along the lines of the former, shareholder calls for stripping CEOs of the Chair role tend to arise whenever CEO-led boards fail in their management oversight roles. Tesla Inc. was recently forced to remove the Chair role from CEO Elon Musk as part of a settlement with the SEC over charges that Musk misled investors over a series of tweets about taking the company private. At Facebook Inc., several public pension funds are mounting pressure on the company through a shareholder proposal request seeking to appoint an independent Chair, citing the company’s recent “mishandling” of controversies, including data privacy concerns raised earlier this year. However, shareholder proposals that ask boards to name independent chairs at some time in the future rarely receive majority support. Of the 491 proposals that went to ballot during the past decade, only 27 proposals have received majority support, and only three proposals passed the majority threshold in the past four proxy seasons (2015-2018).

In this article, we find that, despite these conflicting signals, U.S. boards continue their slow but steady march away from combining the CEO and chair positions and towards establishing independent leadership on the board. Our analysis finds that the choice of leadership structure may have a meaningful impact on other governance and compensation practices, as boards with independent leadership (either via an independent Chair or a Lead Director) are more likely to be more diverse, have a more balanced tenure, are more responsive to shareholders, while their CEO pay levels are less likely to be excessive relative to peers.

Investor Views on Independent Leadership Vary

In the U.S., unlike most global markets, views on independent board leadership vary considerably among investors. Reflecting a global perspective, Norges Bank Investment Management recently published a position paper that unambiguously argues that “the board should be chaired by an independent non-executive member” and (that) “the roles of chairperson and CEO should not be held by the same individual.” The U.S.-focused Council of Institutional Investors’ position is slightly more liberal, stating that “boards should be chaired by an independent director” with the roles combined “(o)nly in very limited circumstances.” The Investor Stewardship Group (ISG) endorses independent board leadership with a more flexible principle that “boards should have a strong, independent leadership structure.” ISG explicitly notes its signatories’ lack of unanimity on the topic: “Some investor signatories believe that independent board leadership requires an independent chairperson, while others believe a credible independent lead director also achieves this objective.” Notably, this split decision on CEO/Chair separation also appears in the recently revised Commonsense Principles 2.0, which are backed by the Business Roundtable and nearly two-dozen high-profile CEOs. Like its earlier version, the revised 2.0 Principles charge a board’s independent directors with deciding “whether it is appropriate for the company to have separate or combined chair and CEO roles” but notes that it is “critical that the board has in place a strong designated lead independent director” when the titles are combined.

Investors’ split positions are evident in vote results of U.S. shareholder proposals that seek the adoption of a policy to establish an independent Chair. The bulk of proposals receive moderate levels of support (around 30 percent of votes cast on average), and very few manage to receive majority support. Unlike most other governance reforms proposed by shareholder proposals proponents, support for independent chair resolutions has remained static during the past decade.

Cross-Market Comparison of Board Leadership

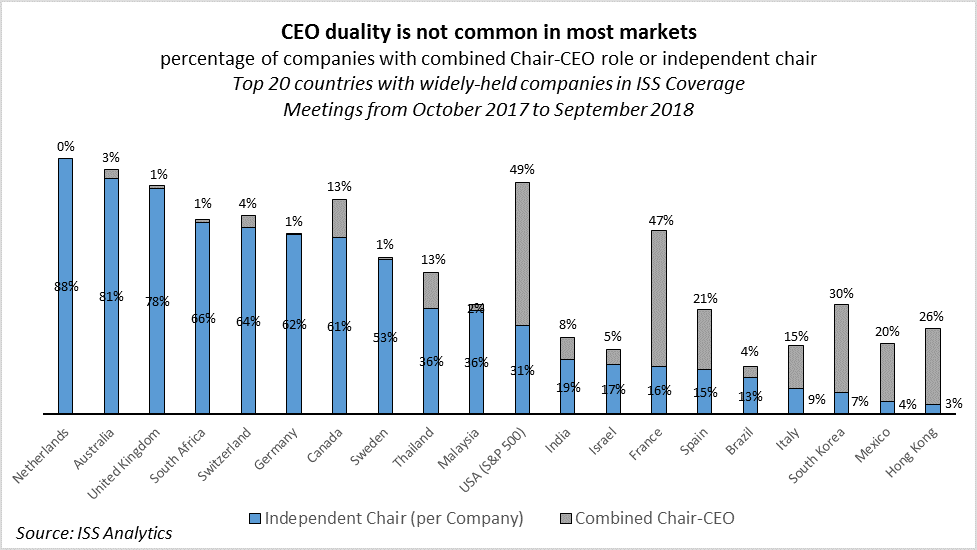

In most global markets, the Chair has an elevated status on the board. The responsibility given to the Chair is not a “duplication” of the CEO’s responsibilities, but rather a plenary, long-term authority beyond the day-to-day operations of the company. In the United Kingdom, the Governance Code mandates the separate roles and that “no one individual should have unfettered powers of decision.” Beyond the Code’s principled position, the 2003 Higgs Review added that no former CEO should go on to become Chair of the company and no person should Chair the board of more than one company due to the responsibilities associated with the position.

The work necessary to fulfill the responsibility is evident in the frequency, or lack therefore, that the position in combined in many of these markets. The only major market with a similar prevalence of CEO-Chairs as the USA is France. In France, however, the expectation is not only that a lead director will be appointed, but there is also a requirement that the company’s bylaws formally detail the specific responsibilities of the role, such as monitoring conflicts of interest, board convening power, setting the agenda, and reporting for the general meeting.

The governance practices in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, generally disfavor the combined CEO-Chair roles and may require companies to take specific measures that counterbalance the combined roles. Furthermore, in markets such as Austria, Germany, Norway, and Sweden, the combination of the CEO and Chair roles is limited by regulations that either restrict the combination of the positions or do not allow the CEO to be a member of the board at all. In most emerging markets, while it is uncommon to establish an independent Chair, the roles of Chair and CEO are typically split, with an insider or an executive serving as the Chair.

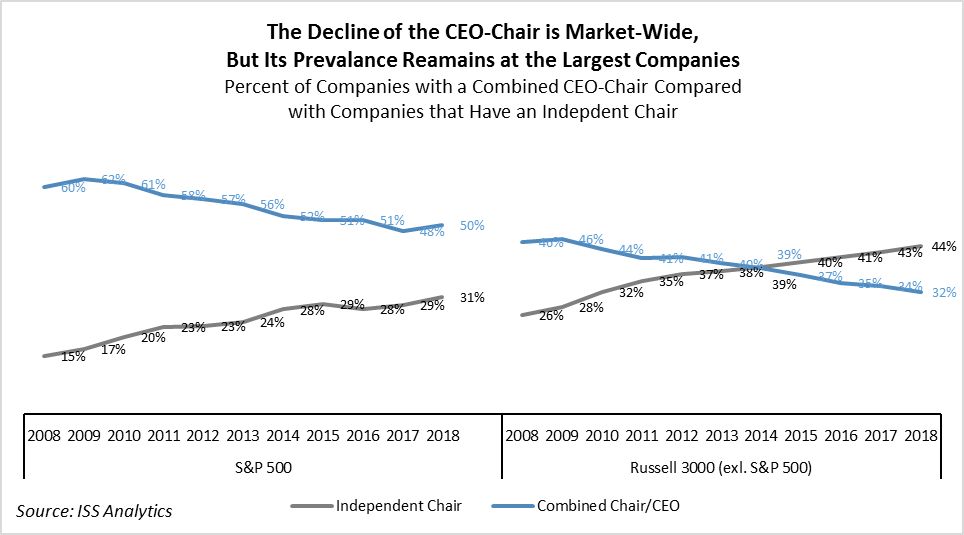

U.S. Companies are Evolving their Board Leadership Structures

While U.S. best practice recommendations differ, and shareholders rarely approve shareholder proposals seeking independent chairs, the past decade has witnessed a significant rise in the number of companies with independent Chairs and a corresponding decline in the prevalence of combined CEO-Chairs. In particular, the percentage of S&P 500 companies with an independent Chair has doubled, from 15 percent of firms in 2008 to 31 percent of companies in 2018. In fact, smaller firms are more likely to appoint an independent chair than combine the two roles, as 44 percent of non-S&P 500 companies in the Russell 3000 had an independent Chain in 2018, compared to 32 percent of companies in the same universe where the Chair and CEO roles were combined.

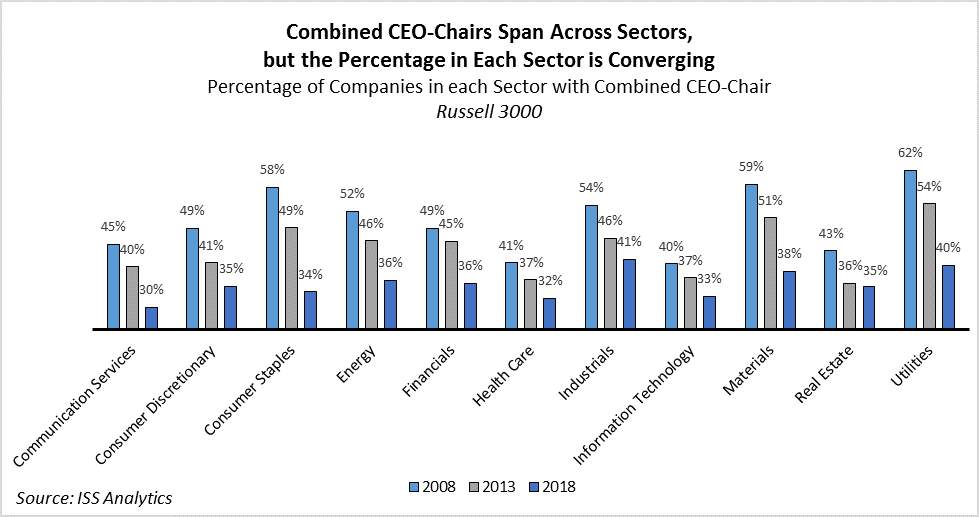

In the same manner that companies of all sizes are moving away from the combined CEO-Chair, all sectors have also seen a decrease in the proportion of companies with a CEO-Chair. The companies with combined CEO-Chairs are dispersed in all sectors; as of 2018, each sector had between 30 to 40 percent of companies with a combined CEO-Chair.

The alternative structure to separating the roles of CEO and Chair has been to appoint a Lead Director to serve as a counterbalance and provide a form of independent leadership. Only 54 percent of companies with a combined CEO-Chair had a Lead Director in 2008, but the practice gained significant traction in the following decade, in line with the overall movement toward independent leadership.

As of 2018, there were only 13 percent of companies in the Russell 3000 that have no form of independent leadership: 5 percent of companies have a combined CEO-Chair and no lead director, and an additional 8 percent of firms had a non-independent Chair and no lead director.

The Interaction of the Board Leadership with other Governance Factors

A closer examination of board leadership structures reveals that the boardroom leadership style selected may have a significant impact other governance practices, including gender diversity, board refreshment, shareholder rights, board responsiveness, and compensation.

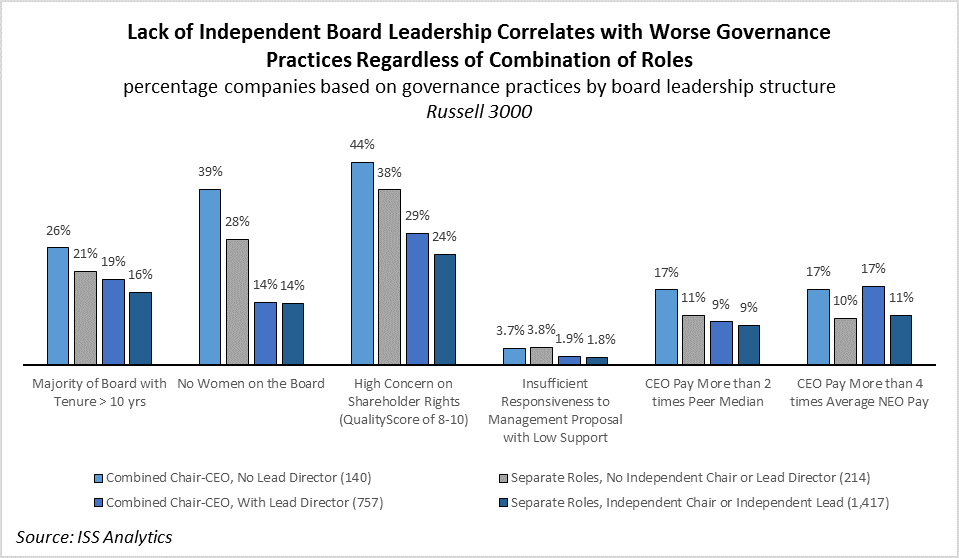

Companies that lack independent board leadership exhibit better governance practices regardless of whether the roles of Chair and CEO are combined. The graph below groups companies in four categories by order of leadership independence: i) combined role with no Lead Director, ii) separate roles with no independent Chair or Lead Director, iii) combined role with Lead Director, and iv) separate roles with independent Chair or independent Lead Director. Companies that lack independent leadership (categories “i” and “ii”) consistently show worse metrics compared to companies that have established independent leadership either via an independent Chair or a Lead Director. In relation to board composition, board refreshment and gender diversity improve as independent leadership on the board increases. In addition, shareholder rights and responsiveness to shareholders also improve with increased board leadership.

On the compensation front, companies that lack board leadership tend to pay their CEO at a higher multiple compared to the CEOs of peer companies. However, pay equity within the C-Suite mainly correlates with whether the roles of Chair and CEO are combined. Combined CEO-Chairs tend to get paid more relative to the rest of their executive team regardless of whether there is a Lead Director on the board.

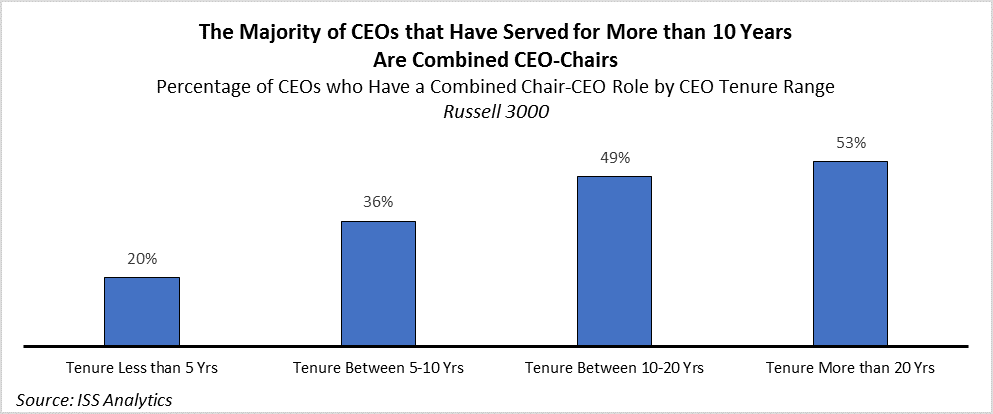

Long-tenured CEOs make up the majority of CEO-Chairs. Anecdotal evidence would suggest that some CEOs have continued with the combined role because of their superior performance for the company, but others have remained in the combined role because of the difficultly in removing a continuing CEO from the Chair position, or the board’s passive position of waiting for the CEO’s retirement as a de-facto succession plan.

The chart below identifies a clear correlation between the CEO tenure and the likelihood that the CEO also serves as the Chair. If a CEO reaches the 10-year mark for service, it is more likely than not that they serve in the combined role. As of 2018, 54 percent of combined CEO-Chairs had a tenure of more than 10 years, while only 29 percent of non-Chair CEOs had a tenure of more than 10 years.

Considerations for Companies and Investors

Succession planning for a CEO-Chair should include an assessment of board leadership. The board should address the cost-benefit tradeoff in allowing for the CEO-Chair to continue in the combined role for a long period of time. While the board requests flexibilty in its leadership structure, the long tenure of CEO-Chairs suggests that, in practice, boards may not have as much flexibility when it comes to changing the leadership structure or creating a succession plan. The succession plan for the CEO-Chair must consider the replacement of both the CEO and the Chair as separate positions. The considerations for board leadership structure in the context of a newly appointed CEO may differ significantly compared to an incumbent long-serving CEO.

Company-specific circumstances should be taken into consideration when evaluating board leadership. When assessing the potential risks of the combined role, investors should review the company’s historical leadership structure and whether the company has recently combined the roles, perhaps for a specific reason, or whether the company is undergoing a transition.

Understanding the overall scope of the company’s governance practices is also important. Compensation concerns, questionable related-party transactions, affiliated or interlocking directors, or lack of responsiveness can all suggest there is not sufficient oversight, while the lack of any such issues may suggest that the board has adopted appropriate structures to avoid conflicts and provide balance.

The lead director should have sufficient duties and responsibilities. Companies should ensure that the Lead Director does not have a leadership role in name only. Comprehensive responsibilities of the Lead Director typically include the approval of meeting agendas, meeting schedules, and information sent to the board, the authority to call meetings of independent directors, and presiding at executive sessions of the independent directors and all board meetings at which the Chair is not present. The independent lead director should serve as a liaison between the Chair and the independent directors, and should be available for director communication and consultation with shareholders.

This post comes to us from Institutional Shareholder Services. It is based on the firm’s recent memorandum, “Independent Board Leadership Matters: Evidence from Governance Practices,” dated November 9, 2018.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog