In 2018, U.S. companies spent $1 trillion to buy back their shares, while they spent $4 trillion to do so between 2008 and 2017. This is raising strong criticism from different quarters in the political sphere. Not only do key Democrats consider it an anathema[1], but Republican Senator Marco Rubio proposed to end the preferential tax treatment of share buybacks.[2] Other Republicans, though, see it as normal.[3]

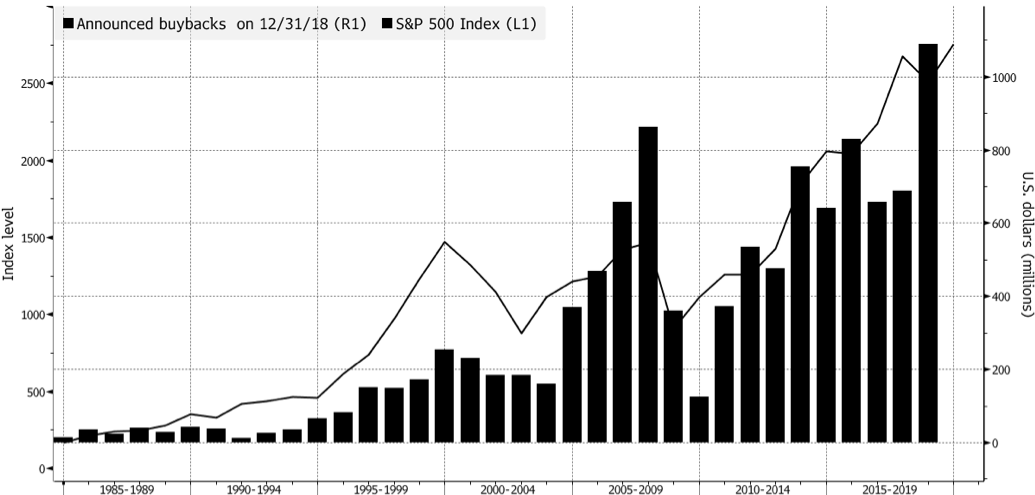

There is no substantial financial and economic difference between the distribution of a special dividend and a share buyback. However, dividends are taxed immediately, while share buybacks induce an unrealized gain until the shares are sold – allowing for tax deferral. From a policy perspective, the sudden surge of buybacks (see chart below[4]) could be explained as an unintended consequence of the recent tax cuts. As we saw recently, companies accelerated amortization for tax reasons in 2017, a year of high tax rates, and bought back shares in 2018 after the tax windfalls of the Trump administration.

Should buybacks be addressed by legislators? One might argue that U.S. stocks will lose the major support they get from buybacks as the quality of corporate debt deteriorates and economic growth slows.[5] But regulators might take a closer look, nevertheless.

Corporations Need Equity Flexibility

The debate on buybacks revolves around the greed of corporate management and the spending of money to benefit shareholders rather than the wider economy. However, to assess the validity of these concerns, it is important to look at the economic fundamentals of why buybacks make sense from a balance sheet standpoint.

In a number of ways, companies manage their equity to maintain the equilibrium between financial stability and their funding cost. The statement of Jamie Dimon, chairman and CEO of JP Morgan Chase, in his letter to shareholders is correct: The need for equity, the biggest expense of a company, depends on the circumstances.[6]

Share buybacks create a double leverage: They reduce the equity, and they increase the debt or reduce the cash. They have, therefore, a serious impact on the robustness of the balance sheet of companies. If a company decides to increase or decrease its capital, it must be for structural and long-term reasons.

A share buyback should therefore occur for structural reasons and with a view to the long-term balance sheet. A few key examples of when a share buyback might be sensible:

- A structural change of a company business model;

- An excess of cash on the balance sheet that is unlikely to be deployed by investments or acquisitions;

- A structural under-leverage that will not be corrected in the foreseeable future; or

- A clear desire to create long-term shareholder value.

A share buyback is the opposite of an increase of capital needed to finance growth. In a sense, a share buyback is a recognition that the company does not have anything better to do with its money than return it to shareholders.

The Process of Deciding on Share Buybacks

Buybacks should resonate with a company’s views of its financial stability, investments, acquisitions, strategy, and business model. Good governance practices should, therefore, be used in reaching buyback decisions, especially since a buyback can affect the very voting metrics with which it is decided.

A blanket authorization at a company’s annual shareholder meeting to the management proposing a buyback is weak governance. Management should explain the impact of a buyback and why the company does not need equity for the foreseeable future, despite its growth strategy. Boards of directors are rarely presented with such an explanation and tend to assume buybacks create shareholder value, which is just one of their mandates.

The impact of the share buyback on the stock price-based incentive compensation of management is too important for the execution to be left to the management or executive committee. It should be executed in stages under a specific approval of the board.

When Does a Buyback Make Sense?

Buybacks make sense only when capital allocation justifies them, as, for example, when holding companies or private equity funds buyback shares to improve their consolidated value. Mid-2018, a large Indian company proceeded to a share buyback. One of the beneficiaries was the holding company of the group. The excess of equity justified the deployment of excess equity in one company into the wider group.

It is in the interest of companies belonging to groups for their parent company to be financially healthy. The parent is, after all, responsible for the group’s financial stability. Such operations are happening in groups and are part of a group strategy.

When Do Buybacks Deserve Additional Scrutiny?

Since share buybacks push up a company’s stock price, it is tempting to use them to counter a falling stock price due to disappointing results. Take the example of General Electric between 2014 and 2017: It repurchased $40 billion worth of shares at prices between $20 and $32 while the company was not undervalued (it is currently trading around $9.30).

Share buybacks are supposed to lead to the extinguishing of the shares acquired, prompting a decrease in shareholder equity. It remains a mystery why General Electric kept the repurchased shares in its portfolio, which artificially kept the equity at its purchase price at a substantial risk: the price at which the shares were bought back was a multiple of the current price. The net result was a loss of tens of billions of dollars when the shares were revalued annually.[7] The only way buybacks can be justified is when the shares are extinguished, and shareholder equity is reduced.

Buybacks often affect stock performance and metrics like earnings per share (EPS). Stock performance most often affects executive compensation. The top management is a prime beneficiary of a share buyback in many cases.[8] Based on an SEC analysis, led by Commissioner Robert Jackson, for half of the 385 buybacks that occurred from 2017 to 2018, at least one executive sold shares in the month after the buyback announcement. Jackson found that, in the eight days after a buyback announcement, twice as many companies had insiders selling shares than they did on an ordinary day.[9] Further research confirms this tendency.[10] This is where the ethical debate arises. There are ways, however, to isolate a share buyback from an increase in management compensation.

Some sectors are more sensitive to the effects of buybacks. Buybacks by banks, for example, can affect the additional cushions required for systemic banks and increase of the capital adequacy and leverage ratios. Since the financial crisis, the efforts of regulators have been focused on the financial stability of financial institutions. In this light, it is disturbing that banks have championed buybacks.

While the debate on sustainability is generally focused on the environment, we should not forget that financial stability is one of its key components. Financial sustainability would be threatened by share buybacks that jeopardize stability, the ability to implement environmental commitments, and the social fabric of a company.

SEC Regulation Rather Than a Partisan Fight

Despite the good intentions of politicians who aim to limit or even ban buybacks, the issue is much more nuanced. As we can see from the above, this is a matter of shareholders, governance, and strategy. The current status of General Electric reminds us of the absurdity of borrowing to buy back shares when the company carries $200 billion of debt.

The SEC polices the fairness and the transparency of corporate actions. The capital increase of a listed company is accompanied by an underwriting process, due diligence, and justification of the board in a prospectus. Share buybacks deserve similar transparency and authorization requirements – perhaps more than under the current Rule 10B-18 regime that covers buybacks. The SEC is right to assess the wider implications of buybacks.

Industry regulators will need to be involved. Regulatory approval of the banking or insurance buybacks is indispensable to the mandate of financial stability. While Jamie Dimon might have excess equity in JPMorgan Chase, other financial firms may not. If stress tests show that dividends may not be distributed, the Federal Reserve may pay closer attention to buybacks by banks.

It is all about the long-term health of a company: buybacks as a financial maneuver to secure short-term share effects (and hence executive benefits) should be discouraged. As M&A lawyer Martin Lipton explains, capitalism based on short-termism is no more.[11] A company must make strategic decisions to improve its market capitalization over a long period of time. Buybacks should not be outlawed, because companies need them as one of a variety of ways to improve their equity allocation. Better regulatory oversight would, however, help reduce buybacks done for the wrong reasons.

ENDNOTES

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/03/opinion/chuck-schumer-bernie-sanders.html; http://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/RI_EndingShareholderPrimacy_workingpaper_201902.pdf

[2] https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/2/20/18225086/marco-rubio-stock-buybacks-tax-plan

[3] https://www.cnbc.com/2019/02/14/republicans-rick-scott-pat-toomey-rip-marco-rubio-over-buyback-tax-plan.html

[4] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-02-14/yell-all-you-want-about-stock-buybacks-they-re-not-slowing-down

[5] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-04-24/end-to-1-trillion-buyback-binge-may-help-uniquely-hated-asset

[6] https://reports.jpmorganchase.com/investor-relations/2018/ar-ceo-letters.htm

[7] Shares of a company’s treasury stock are a different type of transaction all together. They are part of the treasury function of the company and do not include any decrease of equity. However, they need to be capped a 1-2 percent of the equity and 1-2 percent of the trading volume, whichever is the lowest, to ensure that the disposal of the shares will not affect the market and can be rapidly executed.

[8] https://clsblueskybstg.wpenginepowered.com/2018/08/03/how-stock-buybacks-can-affect-executive-compensation/

[9] https://clsblueskybstg.wpenginepowered.com/2018/06/12/secs-jackson-calls-for-curbing-executives-ability-to-cash-out-on-buybacks/

[10] Dittmann, Ingolf and Keusch, Thomas and Obernberger, Stefan, Share Repurchases and Stock Option Grants (January 16, 2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3316793 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3316793

[11] Martin Lipton (2019) https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2017/01/11/corporate-governance-the-new-paradigm/

This post comes to us from Georges Ugeux, chairman and CEO of Galileo Global Advisors and former group executive vice president of the New York Stock Exchange. He teaches International Banking and Finance and a reading class on Brexit at Columbia Law School.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog