Can silence solve problems that words cannot? The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) hopes so, because this premise underlies the confidential filing provision of the Jumpstart Our Businesses (JOBS) Act. But how firms benefit from confidential filings remains unclear, complicating efforts to assess the efficacy of this provision. In our study, we highlight a potentially unintended benefit of the confidential filing provision by showing that filing confidentially helps shield firms from non-shareholder litigation risk in advance of IPOs.

Countless anecdotes describe the IPO period as a uniquely challenging time in the life of a private company. Much of these challenges relates to expectations of heightened disclosure and scrutiny for firms that were previously accustomed to a sheltered existence. Lengthy IPO registration statements reveal significant amounts of information about many aspects of the firm’s business, including products, strategies, financial condition, and risk factors. Then there are the SEC comment letters, which scrutinize the registration statements and frequently require firms to reveal even more about their business. The typical firm responds to four SEC letters during the IPO process. Historically, both the registration statement and the SEC comment letters were publicly available upon filing, leaving the firms with little control over whether and when to reveal information to outsiders.

Encouraging IPOs by keeping them secret

With the growth of private equity and alternative funding sources, IPOs became less and less popular over the early 2000s – a trend that alarmed the SEC enough to prompt a significant deregulation of the IPO process through the JOBS Act. Title I of the act aims to encourage IPO activity by granting managers of emerging growth companies (those with less than $1billion in revenue; hereafter EGCs), an unprecedented degree of discretion over IPO disclosures. Arguably, the most significant provision of Title I is the confidential filing option, which offers EGCs the opportunity to confidentially submit a draft registration statement to the SEC for nonpublic review. Under this provision, firms can keep their information private until 21 days before the roadshow, and should they lose their IPO ambitions, they can walk away without signaling IPO intentions and sharing any information with the public.[1] To compare, in traditional IPOs the registration statement becomes public on average about five months before the IPO.

Confidential filings are incredibly popular amongs IPO firms – close to 90 percent of EGCs opt in for confidential filing. Yet, critics say that confidential filings deny investors time to digest a firm’s financial information. Eight years after the passage of the JOBS Act, we know that IPO firms pay a steep price for this erosion in market transparency in the form of severe IPO underpricing. Given this large cost, why are the vast majority of new issuers opting to file confidentially?

Confidential filings as a means of flying under potential plaintiffs’ radar

An oft-presumed benefit of confidential filing is that IPO firms can withhold information from competitors if the IPO process goes south. But for firms that don’t withdraw, IPO filings eventually become public, and thus most confidential filings merely delay disclosure rather than eliminate it. Since the majority of firms complete their IPO, it seems likely that companies seek other benefits from delayed disclosure. We examine one such benefit: protection from lawsuits, especially from plaintiffs seeking to extract undue profit or harm the IPO process.

Lawsuits are frequently in the works before an IPO. Facebook, Zynga, and Groupon were each sued in the year they filed for an IPO, despite facing few or no lawsuits in the year prior. A former manager at iVillage sued the company over compensation issues shortly before its IPO. Two weeks before Fitbit was to set its IPO price, its direct competitor Jawbone filed two separate lawsuits against the company. Lawsuits are costly – in both time and money – and firms often pay to mitigate litigation risk before IPOs. Alibaba, for example, has purchased over 100 patents in order to reduce the risk of IP litigation during the IPO process. However, many IPO firms do not have such resources, and not all litigation can be avoided. Confidential filing offers IPO firms another, often more accessible, tool to mitigate litigation risk.

Through IPO disclosures, outsiders gain better knowledge of the firm’s products, processes, and financial condition, making the pre-suit investigation and discovery easier for potential plaintiffs, such as competitors, employees, patent monetizers, customers, and other indirect stakeholders. An IPO registration also signals that the firm seeks more financial strength and competitive power and marks the beginning of a period of increased media attention and demand on managerial time. These factors may trigger some stakeholders to undermine or take advantage of the IPO process. We posit that the confidential filing provision of the JOBS Act affects litigation risk during the pre-IPO period by making the IPO process less salient and reducing the time and information available for a detailed analysis of the IPO firm.

To understand how IPO disclosure affects the likelihood of non-shareholder litigation, we develop a comprehensive, hand-collected dataset of non-shareholder lawsuits filed against firms that went public between 2008 and 2014. We investigate how delayed disclosure affects the incidence and the characteristics of lawsuits filed against firms during their IPO period by comparing these outcomes for firms that completed their IPOs before and after passage of the JOBS Act.

Lower litigation risk as an “unintended” consequence of confidential filings

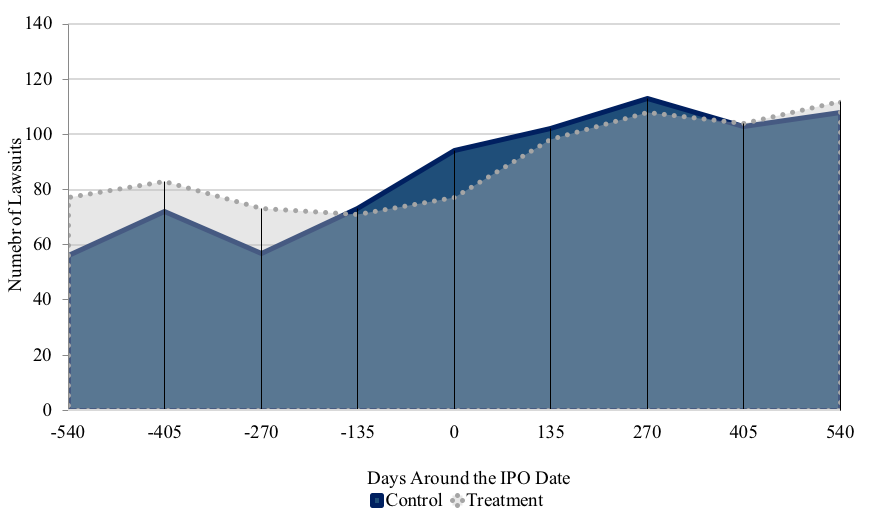

We start our analysis by examining the incidence of lawsuits for firms that conducted their IPOs before the enactment of the JOBS Act, and therefore could not file confidentially. These firms are our control group. We find that these firms are hit with 25 percent more lawsuits during the period between registration filing and IPO date than during a pre-IPO registration benchmark period. We compare this result with the matched sample of firms that opt to file confidentially. These firms, while having a similar incidence of lawsuits as control firms during their benchmark period, are not sued significantly more during the IPO period. Moreover, both samples experience increases in lawsuits following the IPO date, suggesting that the difference in the number of lawsuits between the two groups is confined to the IPO period. In other words, our results indicate that confidentially filing firms likely avoid some of the lawsuits that control firms face around their IPOs altogether, rather than simply having them delayed.

Figure: Number of new lawsuit filings around the IPO date

We find that confidential filings are effective for deterring business-initiated lawsuits but not lawsuits initiated by individuals or not-for-profit parties. This is most likely because businesses rely more on the information in registration filings than do other parties. Another interesting result is that the higher incidence of lawsuits in the control sample during the IPO period is primarily driven by meritless lawsuits, which may be filed to hurt the IPO process or extract undue benefits by exploiting an IPO firm’s heightened incentives to quickly resolve legal issues. Our results suggest that the confidential filing provisions under the JOBS Act help IPO firms avoid the lawsuits that aim to take advantage of firms’ vulnerability during the IPO period.

To determine the benefit of avoiding lawsuits, we examine the relationship between lawsuits and IPO underpricing. We show that, on average, each lawsuit filed by a business during the 90-days before an IPO is associated with a 5.9 percent increase in underpricing on the day of the IPO. Put differently, avoiding one business-initiated lawsuit could have increased IPO proceeds by about $7.1 million for the median firm that went public in 2013. For lawsuits filed by non-businesses, the effect is statistically insignificant.

We note that the stated regulatory motivations for the JOBS Act do not include any discussion of litigation risk, suggesting that our evidence points to an unintended consequence of this act. Our findings inform the SEC about the broader implications of confidential filings, which have been allowed for all firms since 2017, and expand our understanding of how the disclosure of proprietary information affects firms. While confidential filing merely delays, rather than eliminates, disclosure for those firms that go ahead with their IPO, we show that it can still reduce proprietary disclosure costs, which help explain why a vast majority of firms choose to file confidentially despite the large costs associated with it.

Our study is the first to show that reducing disclosure can reduce non-shareholder litigation risk for private firms. In documenting the time-varying and context-dependent nature of litigation risk, our study offers important insights to investors looking to assess the value of an IPO firm. Our results reveal a heightened incidence of meritless lawsuits around IPOs. Failure to recognize this trend likely causes investors to overestimate the uncertainty surrounding the IPOs and thus undervalue IPO firms. By raising awareness of this phenomenon, our findings can help investors appropriately assess the impact of IPO lawsuits on their firm valuation decisions.

ENDNOTE

[1] The FAST Act, which was signed into law on December 4, 2015, reduces this period to 15 days.

This post comes to us from professors Burcu Esmer at the University of Pennsylvania – The Wharton School, N. Bugra Ozel at the University of Pennsylvania and University of Texas at Dallas, and Suhas A. Sridharan at Emory University’s Goizueta Business School. It is based on their recent article, “Disclosure and lawsuits ahead of IPOs,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog