In my new article, Modernizing the Bank Charter, I take a look at the actual practice of regulators when deciding whether to license a bank – or a fintech – and thereby afford them both the burdens and the benefits of supervision by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. I argue that the practice of those who grant charters has been to make sure a bank makes business sense and that the chartering process has been ultra-cautious – even if it does not allow for adequate review and is sometimes too opaque. This caution, however, suggests that the OCC is the right place for a fintech chartering program.

Unlike other corporations, which are entitled to a corporate charter essentially on demand, bank charters have always been difficult to obtain. While corporate charters today permit corporations to operate for “any lawful purpose,” bank charters are only available for companies engaged in the “business of banking”—and that is only the first requirement. To even apply for a charter, bank organizers must submit detailed financial information, business plans, and performance projections to pass muster. They also must make a showing of “public convenience and necessity” for the bank – that the place where the bank wants to do business needs a bank.

These requirements – especially the public convenience requirement – have led some academics to argue that chartering ought to come with more requirements, such as commitments to socially responsible investing, promises of local community investment, or even support for national industrial policy.

These suggestions may be good ideas, but they would be novel. The best way to understand the OCC’s chartering practice, at least as expressed through its cursory written orders, is that it is engaged in “fit and proper” regulation, determining whether the promoters of a new bank are sufficiently experienced, adequately capitalized, and disinclined to break the law. OCC does not charter a bank based on the good works it could do.

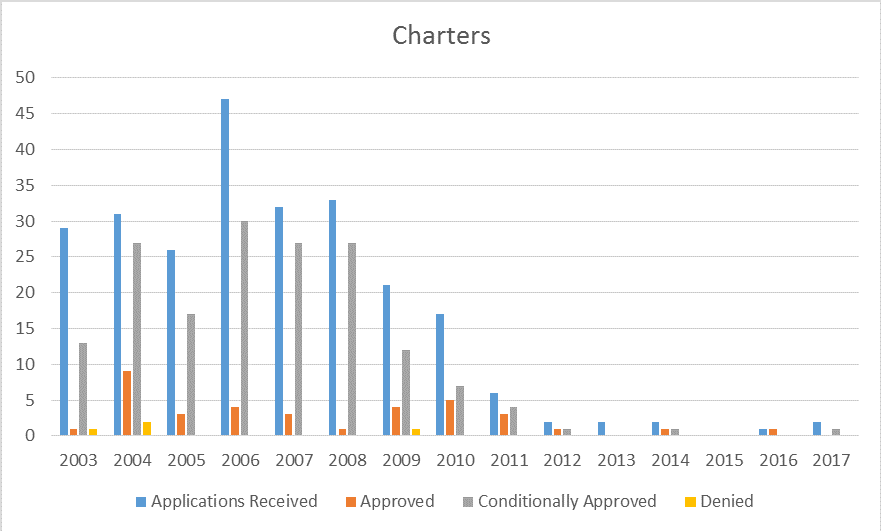

Sometimes, however, it stops chartering banks altogether, as it did, without acknowledging this fact, after the financial crisis, as the chart below demonstrates.

On July 31, 2018, the OCC began accepting applications for its newest proposal for a special bank – the fintech charter. The fintech charter has support from Democratic and Republican Comptrollers of the Currency. The Treasury Department has also expressed support, predicting that peer-to-peer lenders and payments processors might be particularly well served by the charter. The fintech charter has opponents as well, especially those who are concerned that fintech charters could obliterate the traditional distinction between banking and commerce. Lawsuits seeking to undo the OCC’s fintech chartering program have commenced, and state regulators opposed to the federal fintech charter have won a round in district court.

I think these lawsuits are premature. Rather than fully committing to the revolutionary promise of the fintech charter, the OCC has moved deliberately in developing it. There are reasons why fintech firms would benefit from national regulation, as the internet does not stop at state borders, but state fintech chartering is the alternative to national fintech chartering. I have my doubts about the capacity of states to regulate fintechs effectively. The OCC is thought to provide high quality supervision of banks, and so may have more capacity with these limited sorts of nonbanks. The OCC’s approach to the fintech charter should be welcomed and questioned only if it starts extending the charter to the giant internet platforms, such as Apple Pay, Google Wallet, or Amazon’s payment system (as Amazon’s Chinese equivalent Alibaba has done in China with its payment system).

My article provides the first comprehensive account of how the OCC’s chartering practices actually work since Kenneth Scott’s government-funded analysis of the charter in 1975. I offer four actionable prescriptions to policymakers:

- The first is directed to the OCC and FDIC, which should issue guidance reflecting their willingness to entertain charter applications by new banks, guidance that they can update when they feel that conditions warrant.

- The second is directed at courts, which should, the next time they hear a dispute over a charter grant, definitively apply Chevron deference and “hard look” review to the decision by the regulators, instead of taking their current position that OCC chartering decisions are all but unreviewable.

- The third is also directed at courts, which should conclude that the fintech charter, as OCC has articulated it, should be deemed to be within the power of the agency and a reasonable interpretation of its statutory authority, with some promise to offer consumers inexpensive access to financial services.

- The fourth is directed at Congress, which should, if it wishes to have firms like Amazon enter the business of banking, pass a fintech chartering act expressing its permission.

Chartering has picked up again, and the fintech charter, and its limits, are live issues. It is worth thinking through the way the charter exists today now that both scholars and regulators want to change the charter in the future.

This post comes to us from Professor David Zaring at the University of Pennsylvania. It is based on his recent article, “Modernizing the Bank Charter,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog

A bank charter is an official document permitting a banking company to commence business as a bank. It authorizes banking operations. A bank charter includes the articles of incorporation and the certificate of incorporation. The charter specifies the rights of a banking institution.