There is a quote that is commonly misattributed to Mahatma Gandhi: “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.”

At the regular get-togethers in the responsible investment industry, war stories are frequently exchanged about the amused responses to environmental, social and governance (ESG)-related pitches; the confusion; the doors shut in faces. There are plenty of examples of the first two stages of the process.

It should be heartening therefore for the responsible investment industry to discover that it has matured to the extent that some of its more common shared understandings are now under attack – there is sufficient acceptance of responsible investment that there is mileage to be made in being a contrarian! A recent ISS Market Intelligence report identified $60 billion net flows into US ESG funds alone.

While it is often productive to question shared assumptions (and the shibboleths that accrete around them), at the same time one should be prepared to confront skeptics and examine their positions from all sides.

Recent examples include:

- generalizations about the fairytale motivations of the broader responsible investment movement, from the perspective of an insider of a firm that has come quite late to the ESG investing table. While impact can be hard to quantify, ISS ESG has observed an increasing desire on the behalf of clients to achieve real-world outcomes through the use of voting practices.

- criticisms of the value of sustainability reporting, apparently promoted by a 20-year cohort of professionals called ‘Sustainability Inc’ – a criticism which is difficult to reconcile with the constant clamor from responsible investors for more and better data.

- suggestions from less sophisticated market participants that ESG ratings are confusing and complex, and the somewhat short-sighted reaction that ‘beautiful’ risk measures are the solution that will leave ratings behind – it is not accurate to present a dichotomy between stakeholder-sourced risk-based data on the one side and corporate disclosures on the other: both should inform a mature ESG Rating, and indeed both are included in the ISS ESG Corporate Rating. Users should also be wary of a bias toward emphasizing ‘negative’ events, whereas one company may be materially outperforming another across any combination of E, S, or G issues – this is where the ratings space thrives.

There are certainly valid criticisms that must be heeded in each of these papers, but we should also apply a sprinkling of caveat emptor. Absolutely, there are challenges for ESG ratings given variation in outputs across different providers, but users will benefit from a richer understanding of the ESG factors at play if they take the time to delve into the respective methodologies of each firm. Certainly, the government needs to play a bigger role in developing society-level changes in corporate and individual behavior, but there is no reason that this should come at the expense of decades of good work developing corporate reporting frameworks. We should definitely guard against greenwashing as larger, less values-driven asset managers adopt responsible investment practices, but to tar all, or even a material portion, of market participants with this brush risks punishing long-term players in the space for their success.

One of the more courageous recent salvos fired at the responsible investment establishment is based on work suggesting that there is no such thing as ‘ESG alpha’, and the established body of research with findings to the contrary has confused ESG with more standard ‘quality’ measures. Given the considerable amount of work that ISS ESG has done over the years linking ESG factors with performance, this claim merits particular attention.

Firstly, there is agreement that changes in ESG performance and levels of ESG across a portfolio are correlated with various style biases – this finding gels with ISS ESG research on the subject. It is the subsequent conclusion that ESG is not a worthwhile factor that is problematic: just because quality as a factor was published on earlier than ESG factors does not mean it is the factor one should focus on, and that ESG needs to add alpha above it. Why not the other way around – does quality add alpha beyond what ESG already provides? The study also notes that levels of ESG across a portfolio are correlated with quality, and because quality has outperformed this has driven ESG outperformance, leading to the conclusion that ESG is not adding alpha. What if ESG caused the good quality in the first place, however? One can make a case that strong ESG performance will lead a firm to improve treatment of customers, suppliers, employees, the environment, and shareholders, thereby boosting sales and reducing costs. Or perhaps the good quality led to investments in ESG that had these impacts.

ISS ESG has recently published a significant study, ESG Matters II, that considers many of the topics raised above. A key finding from this research is that improving profitability and growth are related to positive change in ESG Performance.

Source: ISS ESG; ISS EVA data

The paper highlights that higher EVA Margin, EVA Spread, and return on invested capital are all associated with improvements in ESG Performance going forward.

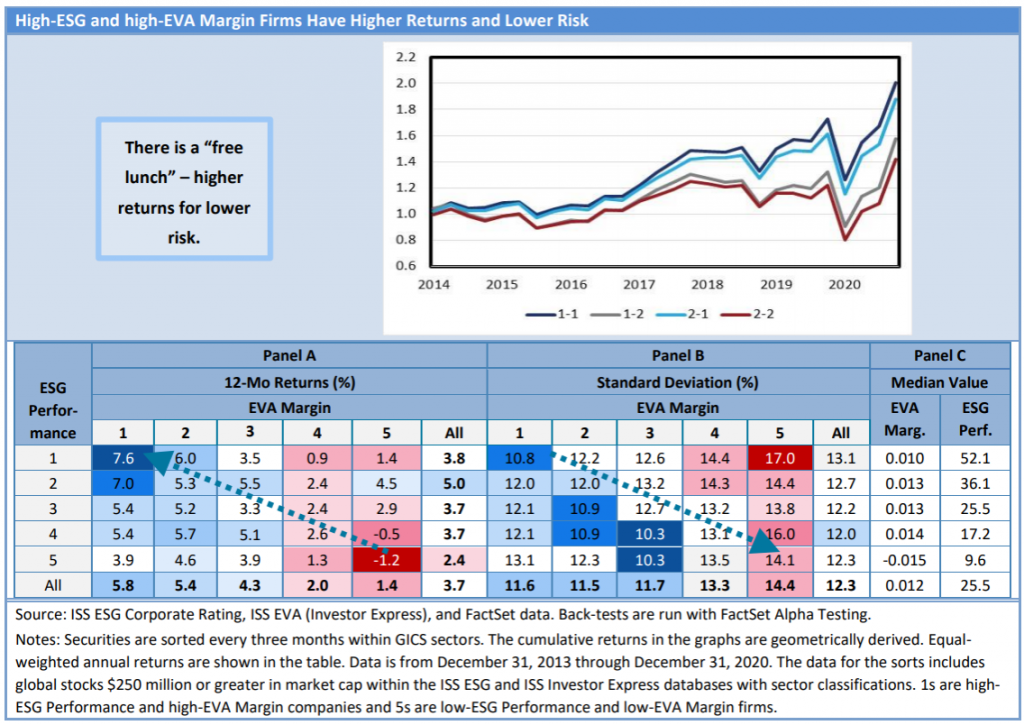

We would also note that the research that fails to establish a link between ESG and alpha raises concerns with sector bias in the source of ESG data referenced. The recent study referenced above is sector-neutral, so the complaints about sector bias do not apply (for instance, ISS EVA data does not necessarily show the technology sector as the best performer and the energy sector as the worst performer, as was the case in the paper under discussion). ISS EVA research also contradicts the finding that use of ESG factors does not offer downside protection. Figures 16-17 of the paper demonstrate that when ESG is combined with EVA Margin it provides good downside protection.

The paper does raise interesting questions around the issue of attention shift, suggesting that increasing attention to ESG may be driving returns, and higher valuations now could result in lower future returns. These are reasonable arguments and ISS EVA’s paper (figure 51) also shows that correlation between ‘E’ factors and returns is rising. But how is this – high and low attention markets to ESG – different from the style rotations observed with traditional factors such as value, quality, size, etc.? Experience and research suggest that all factors tend to go through high- and low-attention states (i.e., there are risk-on versus risk-off markets); thus, one would expect the same to occur for ESG. For some reason, the critics don’t dismiss those other factors because of these rotations, but they do for ESG. The recent spate of criticisms of responsible investment are no doubt well intentioned, and in most cases contain important points that industry players should pay heed to. But responsible investors should also take heart from the fact that sustainable investment is now so strongly positioned at the heart of mainstream financial practice that it should become the subject of sniping, however accurate. After all, not that long ago that used to be us! And every criticism faced and taken on board brings the finance sector closer to the ultimate goal of a win for global sustainability!

This post comes to us from Institutional Shareholder Services. It is based on the firm’s article, “Commentary: Coming of Age – ESG Investing Stands Up to The Critics,” dated June 17, 2021, and available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog