Water means life. More than half of our bodies consist of water, and it is an indispensable resource for production of food and other goods. It is fundamental for societies and ecosystems alike. While water covers approximately 70% of our planet’s surface, only 0.5% is freshwater that is readily available in lakes and river systems. Over the last few decades these freshwater resources have come under increasing pressure due to population growth, climate change, and unsustainable production and consumption patterns.

According to the UN World Water Development Report 2020, global demand for water has been increasing by 1% annually since the 1980s, and over 25% of the world’s population already live in water-stressed areas. Considering projections of a 40% gap between water demand and supply worldwide by 2030, and the potential for more than 700 million people to be displaced due to lack of access to water, it becomes clear that the water crisis is a global crisis – even though water risks are inherently local in nature. Water is also a key part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with Goal 6 focused on access to Clean Water and Sanitation for all by 2030.

Beyond the humanitarian and environmental impacts, the water crisis constitutes an economic risk with implications for the business community and its investors. In the words of Kirsten James, director of Ceres’ water program: “The global water crisis is a global risk. Investors really need to be key players.”

Understanding Water Risk from an Investor Perspective

Institutional investors can mitigate water risks across their investment portfolio by identifying industries and business activities that depend on or greatly impact water resources, and actively engage in management decisions to reduce negative impacts on water and related risks.

The source of water risk can be broadly divided into two categories:

- Risk due to basin conditions: Physical risks that are derived from the broader basin context in which a business and/or its suppliers operate.

- Risk due to the company: Risks that stem from a business’ operations, including its products and services, which could harm the environment and impact communities’ access to water.

All these risks can have financial implications such as reduced company revenue, an increase in operating costs, or an impairment to long-term business viability due to water-related challenges. For instance, some business models depend on large quantities of water of a specific quality, while others can face reputational risk arising from poor management of water-related impacts. Understanding and identifying companies based on these risks can therefore be a powerful resource for portfolio allocation.

Determining Exposure to Water Risks at a Company Level

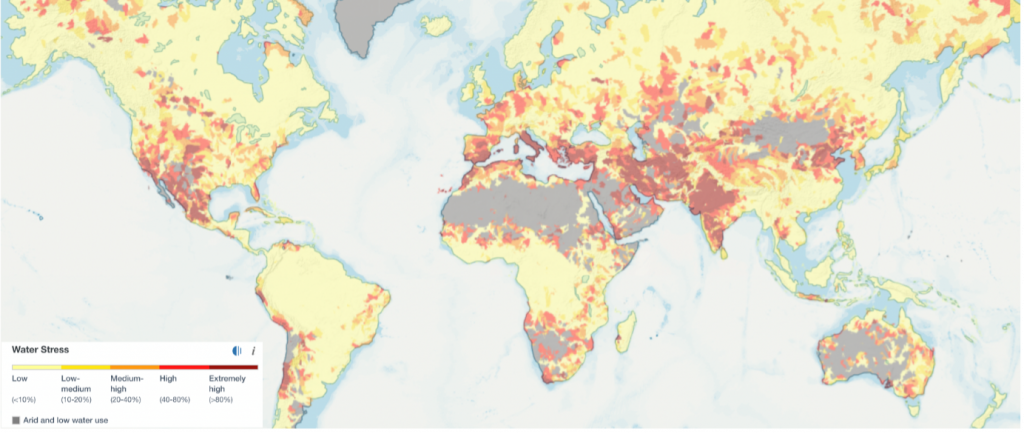

Baseline water stress measures the ratio of total water withdrawal to available renewable surface and groundwater supplies. Based on World Resources Institute (WRI)’s Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas, countries such as Qatar, Israel, and India rank among the countries with ’extremely high’ levels of baseline water stress, where irrigated agriculture, industries, and municipalities withdraw more than 80% of their available supply on average every year. Forty-four countries are assessed as having ’high’ levels of water stress, with more than 40% of their water supply being withdrawn annually. This narrow gap between supply and demand could make businesses vulnerable to fluctuations such as droughts or increased water withdrawals.

Figure 1. Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas

Source: WRI

In addition to the geographical footprint, the industry-specific nature of a company’s own operations and its dependencies on supply chains can point to water risks in portfolios. Analysis should go beyond water consumption intensity and reflect risks regarding water pollution and wastewater disposal. Research studies by the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the CDP Water Impact Index rank industrial sectors such as Mining, Chemicals, Fossil Fuels, Food and Beverages, Apparel, and Manufacturing among those at the highest risk of water insecurity.

An analysis of the Water Risk Exposure Classification, an element in the ISS ESG Water Risk Rating of 7,800 issuers (as of January 2023) placed a quarter of the companies in a high freshwater-risk exposure category after combining industry and supply chain risk exposures with company-specific geographical activity profiles. The industries with the highest share of companies in this category are Chemicals, Food Products, and Mining & Integrated Production. Some companies from industries with comparatively low water-risk profiles, such as the Telecommunications or Electric Utilities industries, also land in this category because of their exclusive presence in countries with very high levels of water stress. This highlights the importance of a broadly encompassing analysis.

Identifying Companies with Poor Water-Risk Management Practices

Companies’ potential negative impact on water resources may not resonate well with investors, customers, and other stakeholders in the midst of a global water crisis. These risks are realized through corporate controversies stemming from stakeholder scrutiny of company operations that undermine water rights and access to water for local communities: for instance, when a company fails to prevent water pollution, mitigate water risks, or implement sufficient remediation measures.

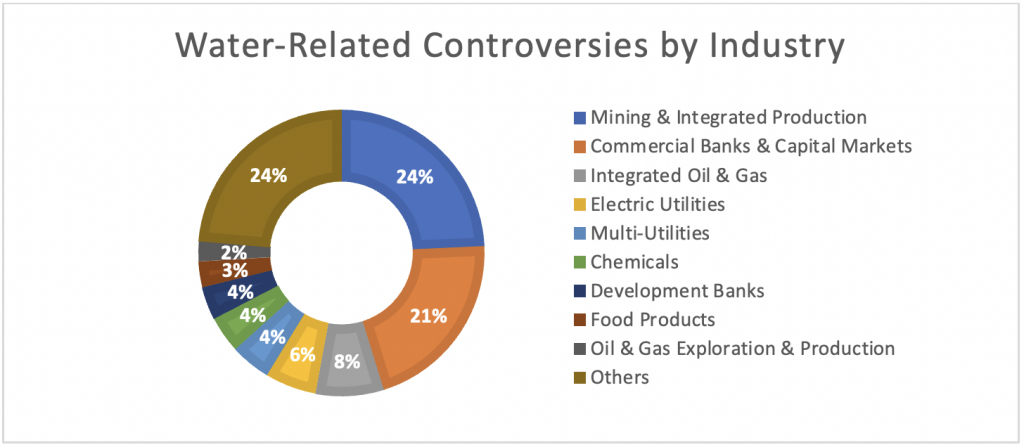

ISS ESG’s Norm-Based Research (NBR) has identified 339 publicly held issuers currently involved in water-related controversies. At industry level, these controversies primarily occur in the Mining, Oil and Gas, and Electric Utilities industries, as well as in Financials, with 22% of all water-related controversies having a severe or very severe impact. Examples of water-related controversies include

- repetitive oil spills in Nigeria allegedly impacting groundwater sources and contributing to human health hazards;

- a tailings dam breach in Brazil allegedly contaminating rivers and impacting the local water supply of more than 1,000 residents of nearby indigenous communities; and

- the diversion of several rivers due to a hydroelectric project in Chile that threatens access to water for up to 8 million people.

Figure 2. Industries Involved in Water-Related Controversies

Source: ISS ESG Norm-Based Research

After determining the risk exposure of a particular company, practices and efforts taken to mitigate the risk need to be assessed for a more comprehensive analysis. As an example, companies active in regions with no water stress can still negatively impact communities through controversial business practices, while companies exposed to high industry risks can take effective measures to reduce externalities. Effective mitigation measures include using less water-intensive irrigation techniques; implementing water-efficient technologies and processes; and treating, reusing, and recycling wastewater.

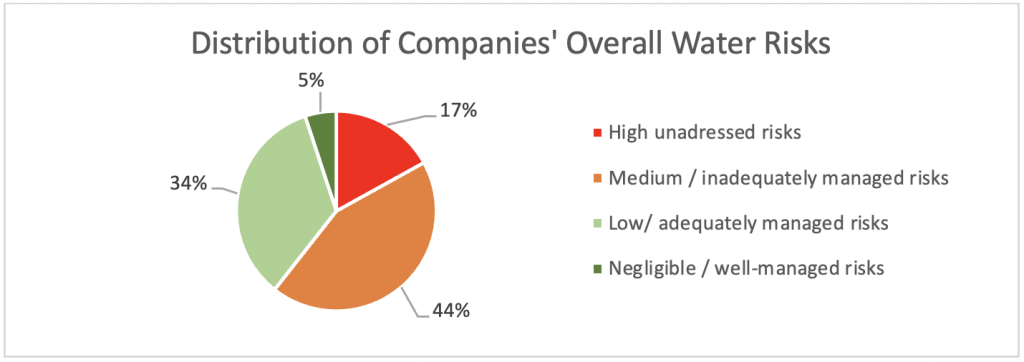

The existence and comprehensiveness of such measures and strategies are assessed by the ISS ESG Corporate Rating and constitute a relevant element in ISS ESG’s new Water Risk Rating, which takes into account the extent to which a company mitigates freshwater-related risks based on its specific baseline risk exposure. By incorporating risks posed by freshwater-related issues to the company’s business model (such as water stress or water dependency), as well as ESG risks linked to potential adverse impacts of corporate behavior on water (for example, relating to high freshwater consumption or freshwater pollution) the Water Risk Rating provides a holistic assessment of a company’s overall freshwater-related risks. Results illustrate that more than half of the 7,800 issuers covered (as of January 2023) do not address or do not adequately manage their high or medium water-related risk exposure.

Figure 3. Companies’ Water Risks (as of March 2023)

Source: ISS ESG Research

Corporate Engagement on Water Stewardship

To further support investors seeking to improve their portfolio’s impact on water, ISS ESG’s Thematic Engagement Solution enables investors to participate in a joint outreach and dialogue with a select list of target companies. The Water Thematic Engagement, which aims to encourage companies to improve their transparency around water-related strategy and risk management through the disclosure of key metrics and targets, focuses on laggards in two industries with high water-risk exposure in both their supply chains and direct operations according to ISS ESG’s Water Risk Rating: Chemicals and Textiles & Apparel. The engagement objectives center around water management strategies, reducing pollution, management of wastewater, and water use reduction targets. In Q3 2022, ISS ESG initiated engagement, on behalf of signatory investors, with 30 companies for an engagement cycle of two years. To date, 70 percent of the companies have responded to ISS ESG’s outreach.

Marking World Water Day

World Water Day falls on the 22nd of March every year. Supported by the United Nations, the day is intended to celebrate the importance of water to global society, and to highlight the plight of the 2 billion members of the global population who currently live without access to safe water.

Through the Water Risk Rating, ISS ESG clients are able to ensure that their portfolios are thoroughly covered on this critical topic, from asset selection and retention to engagement and active ownership practices.

Explore ISS ESG solutions mentioned in this report:

- Access a holistic assessment of companies’ exposure to freshwater-related risks using the ISS ESG Water Risk Rating.

- Identify ESG risks and seize investment opportunities with the ISS ESG Corporate Rating.

- Assess companies’ adherence to international norms on human rights, labor standards, environmental protection and anti-corruption using ISS ESG Norm-Based Research.

- Develop engagement strategies, define achievable engagement objectives and manage your engagement process with ISS ESG’s Norm-Based Engagement Solution and Thematic Engagement Solution.

- Understand the impacts of your investments and how they support the UN Sustainable Development Goals with the ISS ESG SDG Solutions Assessmentand SDG Impact Rating.

This post comes to us from ISS ESG, the sustainable investment arm of Institutional Shareholder Services. It is based on the firm’s article, “Navigating the Water Crisis: Insights into Water Risks from an Investor Perspective,” dated March 24, 2023, and available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog