Regulators globally are requiring companies to disclose their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. For companies in some industries, Scope 1 and 2 emissions – covering, respectively, emissions from direct fuel use and from acquired energy – will cover most relevant emissions caused by their activities, and these are relatively simple to calculate and disclose.

For most companies in the financial sector, though, the bulk of relevant emissions are categorised as Scope 3 indirect emissions, specifically, financed emissions. These are much more problematic to calculate or estimate. Regulators, however, are likely to demand that companies disclose these emissions; otherwise, reporting will be limited to emissions that are marginal to the real impact these companies have.

Attention to Scope 3 emissions is likely to grow, as the financial sector has a key role to play in financing a transition to a low-carbon economy. The financial companies can play this role both by reducing their financing of carbon-intensive industries and providing the capital required by sustainable alternatives.

ISS ESG assesses the readiness of financial companies to disclose and mitigate their carbon impact. This post uses data from the ISS ESG Corporate Rating and from ISS Economic Value Added (EVA) to assess the readiness of financial companies, across different markets and regulatory jurisdictions, to meet this challenge.

Various areas show marked differences in how prepared their financial companies are to meet increased disclosure requirements. Some jurisdictions—e.g., the Netherlands, France, Taiwan—exhibit high preparedness, while others—e.g., the United States and India—exhibit low readiness in anticipation of new regulatory requirements and expectations.

Companies that better disclose financed emissions tend to perform better in demonstrating strategies to mitigate their GHG impact and increasing financing of low-carbon alternatives. These companies also demonstrate stronger financial performance, which suggests a positive correlation between climate responsibility and strong profitability.

The Regulatory Wave

Mandatory climate disclosures are coming into force across the world. The European Union, the United Kingdom, Singapore, Japan, and New Zealand are among those that are incorporating Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and/or International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) frameworks into the required financial disclosures regulations for listed companies. In 2024, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) finalised rules mandating that companies record and disclose a range of climate risks and environmental data. Despite a staggered introduction across different geographies and company sizes, the trajectory for the next few years is clear: climate disclosures are no longer voluntary.

The TCFD framework, introduced in 2017, is the most widely implemented standard. TCFD requires companies to disclose Scopes 1 and 2 emissions, though Scope 3—the most relevant category for financial institutions—is not obligatory. In 2023, the G20 endorsed the ISSB’s standards, then under development, for climate-related disclosures, as well as for other aspects of ESG. These standards have since been finalised and companies are expected to start disclosing against them as early as 2024. Governments will now have the ability to choose how such standards will inform or be incorporated into national regulations.

In 2023 the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) came into force, requiring subject companies to report against the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), which incorporate TCFD reporting together with existing European Union frameworks. Companies are expected to begin disclosing by 2025.

Disclosures on climate strategies and performance can prove a useful decision-making tool when assessing companies’ exposures to transition risks. However, with the first year of reporting already around the corner, how have companies positioned themselves in preparation for the new regulatory requirements across the globe?

Company Preparedness for Regulation: ESG Performance and Transparency

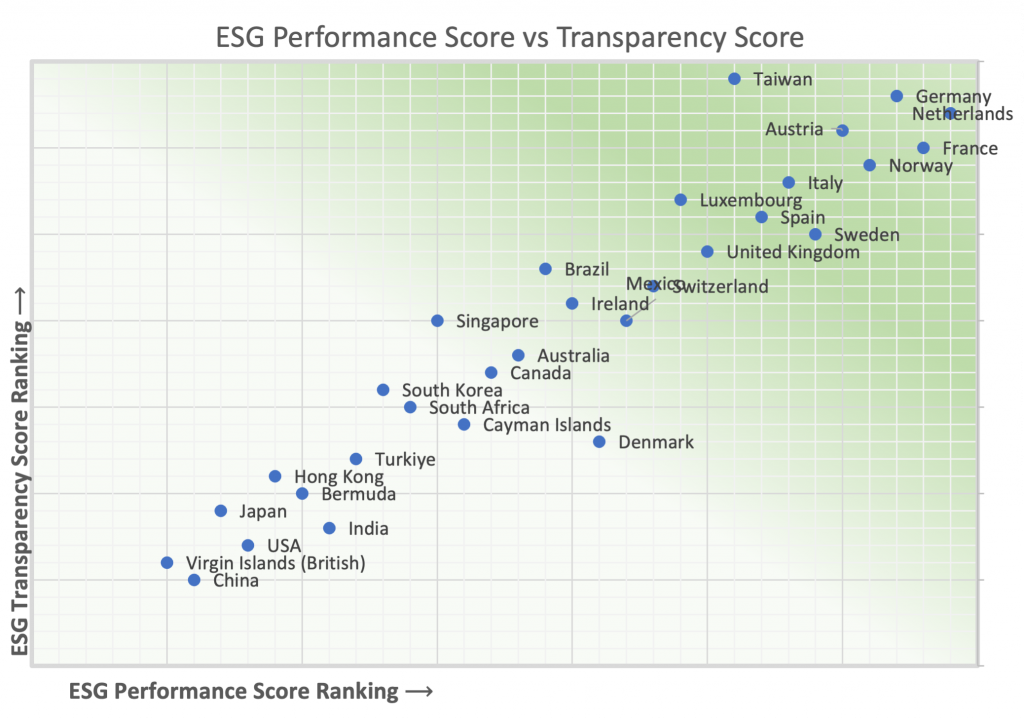

Figure 1 below breaks down the ISS ESG performance of companies within the financial sector across jurisdictions. To estimate the level of preparedness in anticipation of increased future legislation, the figure uses ISS ESG performance data to map the average ESG Performance Score against the average ESG Transparency Scorefor each jurisdiction in which a company is incorporated.

In Figure 1, the 30 most-represented jurisdictions across the financial sector have been ranked, with the ascending Transparency Score rankings on the y-axis and the ESG Performance Score rankings on the x-axis.

Figure 1: Mapping Jurisdictions by Average ESG Score and Transparency Level

Note: Data for 2,742 companies in the financial sector across the 30 most-represented jurisdictions

Source: ISS ESG

Many (though not all) of the jurisdictions in the top right are in the European Union or mirror the EU in sustainability disclosure requirements (Norway). This may be due to the EU’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), which has been in place over the past decade and incorporates sustainability disclosures. In contrast, large Asian markets such as India and China, as well as the United States, perform relatively poorly on the ESG Performance Score and ESG Transparency Score.

Interestingly, Taiwan performs well in both categories: of the 34 Taiwanese financial companies in the dataset, 35% of these financial companies are rated Prime, a status awarded to the top ESG performers in the industry, and 85% achieve a ‘Very High’ level of transparency. (ISS ESG research has previously highlighted Taiwan’s ESG transparency.)

These high scores may reflect a regulatory drive: in 2021, the Taiwanese Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC) set out guidelines for banks that encouraged domestic banks to disclose climate risks in line with TCFD. Furthermore, the FSC requires that the largest listed companies disclose carbon emissions and energy consumption data, with smaller issuers expected to disclose by 2026.

Regulation of Financed Emissions

By far the largest impact financial companies may have on combating climate change and the transition to a sustainable economy may likely be through financed emissions. Therefore, the measurement and disclosure of these emissions is key to assessing the sustainability of financial companies.

Hence, the new ISSB standards require companies engaged in asset management, commercial banking, and insurance to disclose their financed emissions. The United Kingdom and Japan, both of which have large financial services industries, have indicated they are likely to adopt the ISSB standards as mandatory requirements.

In parallel, in the EU, the sustainability reporting standards required by the CSRD will require financial companies to report estimated Scope 3 financed emissions, according to the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) methodology. PCAF seeks to develop GHG accounting for loans and investments, and member companies commit to implementing these standards and disclosing their portfolio emissions.

By contrast, in the United States, the SEC’s climate disclosure rules, finalised and adopted in March 2024, do not mandate disclosure of Scope 3 emissions, making the rules less extensive than previously expected.

Nevertheless, despite this feature of the new rules, many American companies will likely be subject to CSRD or ISSB in some form, because these companies do business in Europe or in jurisdictions that have committed to or adopted ISSB. Therefore, many U.S. financial companies operating internationally will likely report beyond the requirements imposed by the U.S. regulator, potentially including financed emissions.

Company Preparedness: Portfolio Emissions

ISS data can shed light on which countries’ financial institutions are well prepared for this anticipated increase in disclosure.

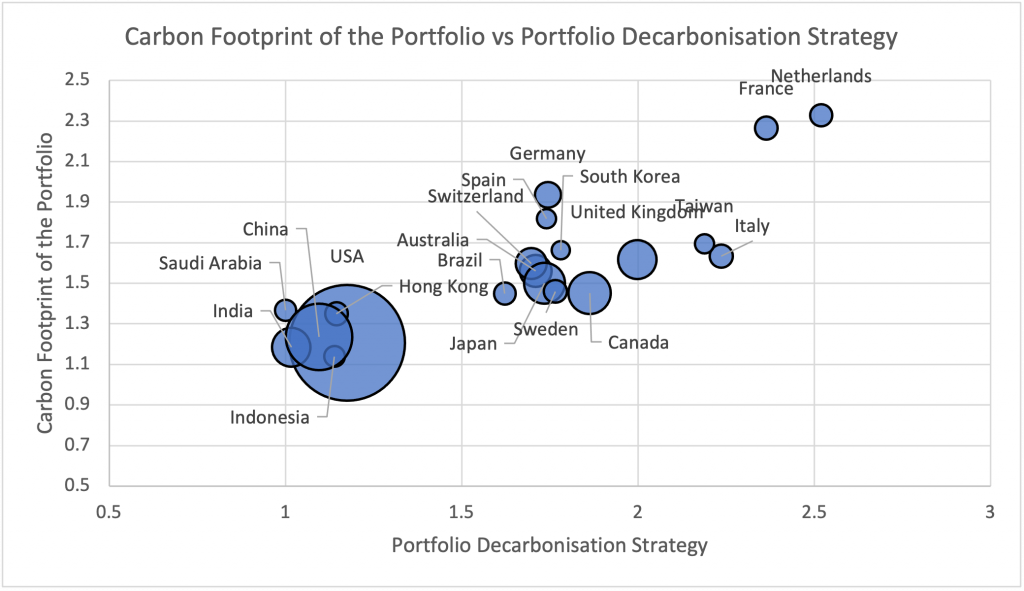

The Carbon Footprint of the Portfolio indicator assesses the level of detail with which a company measures and discloses the carbon footprint of its investments, including which sorts of investee company emissions (Scopes 1, 2, and 3) are measured and the proportion of investments covered. In addition, the Portfolio Decarbonisation Strategy indicator assesses how financial institutions are committed and acting to reduce the climate impact of their portfolios and finance low-carbon alternatives.

Figure 2 shows the average scores for financial institutions on these two indicators, by jurisdiction, covering the 20 largest markets by collective market capitalisation of companies assessed. The population here includes all financial companies in the ISS ESG Corporate Rating universe which generate income from investing activities and for which portfolio emissions are therefore a material sustainability issue.

Figure 2: Mapping Jurisdictions by Average Portfolio Decarbonisation StrategyScore vs Average Carbon Footprint of the Portfolio Score

Note: Bubble size represents the collective market capitalization of the companies assessed within that market. The 20 largest markets are shown. The dataset comprises 1,187 companies.

Source: ISS ESG

There is a relationship between performance on the Carbon Footprint of the Portfolio and Portfolio Decarbonisation Strategy indicators, suggesting that more detailed disclosure is associated with better defined decarbonisation measures. This relationship may indicate that as regulators increase required disclosures of financed emissions, investors may also obtain more information on the efforts companies are taking to decarbonise their portfolios.

It is perhaps unsurprising that companies based in the Netherlands have the highest average scores for both indicators, given that the PCAF originated with a group of Dutch financial institutions. Many high-scoring countries are members of the European Union (or the European Economic Area, as in the case of Norway), where, as mentioned above, Scope 3 reporting requirements based on PCAF are likely to be implemented.

Companies in the United Kingdom, an important market for financial services, have moderately high average scores for disclosure, though relatively low ones for Portfolio Decarbonisation Strategy. A possible explanation is that although disclosure expectations in the United Kingdom are high, London’s systemic importance as a global financial centre has made strong decarbonisation commitments relatively more difficult for its financial institutions.

In contrast, despite the prospect of imminent regulation, financial institutions in the United States show low average scores on both metrics, suggesting that most of these American companies disclose little or nothing about financed emissions and do not display decarbonisation strategies. Companies in India and China also perform very poorly on these metrics. Investors in these three key markets may want more information about how financial institutions are or are not contributing to a transition to a sustainable economy.

Corporate Leaders: ESG and Financial Performance

Some companies are ahead of the curve in providing a strategy to reduce their financed emissions. However, investors may want to know whether these companies perform well on broader ESG metrics, as well as whether such performance complements financial strength.

ISS data allows for reviewing the performance of the leading companies as regards ESG, profitability, and valuation. In particular, ISS Economic Value Added (EVA) provides a measure of a company’s true economic profitability by subtracting the cost of capital from a company’s adjusted operating profit.

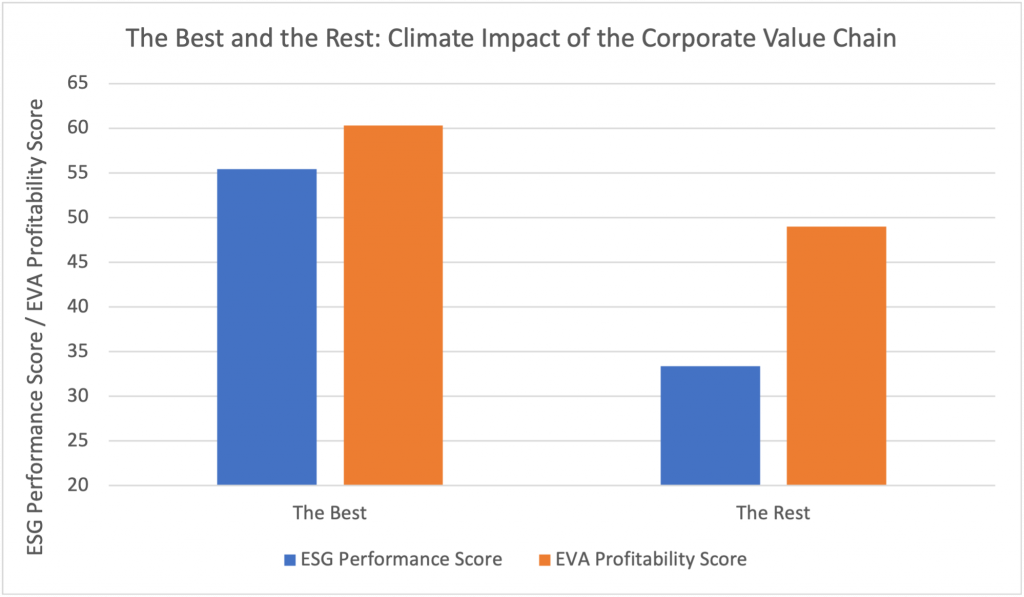

Within the ISS ESG Corporate Rating, the topic Climate Impact of the Corporate Value Chain comprises three indicators: Carbon Footprint of the Portfolio, Portfolio Decarbonisation Strategy, and Monitoring and Reporting. The topic is an overall measure of a company’s effectiveness in disclosing and managing the climate impact of its portfolio.

Figure 3 shows the performance of the top 100 highest-scoring companies in this topic (‘The Best’), as well as of the remainder of companies (‘The Rest’), on two metrics:

- ESG Performance Score: An index of a company’s performance across relevant Environmental, Social, and Governance topics (50 is the threshold for a ‘Prime’ rating, i.e., best-in-class performance)

- EVA Profitability Score: A percentile ranking of a company’s profitability and trend profitability, as measured by EVA (a score of 50 means a company ranks better than 50% of its peers).

Figure 3: Average Performance on Climate Impact of the Corporate Value Chain of the Top 100 Performers (‘The Best’) versus All Other Financial Companies (‘The Rest,’ 1408 Companies), by Different Metrics

Source: ISS ESG, ISS EVA

‘The Best’ companies outperform ‘The Rest’ on these metrics. This is unsurprising as regards the ESG Performance Score, as companies that show greater social and environmental responsibility would likely tackle the key topic of financed emissions.

Furthermore, the higher EVA Profitability Score for ‘The Best’—signifying overall higher EVA and higher recent EVA growth—shows that strong financial performance and a responsible decarbonisation approach are not exclusive. The costs of demonstrating a decarbonisation approach are evidently not an impediment to strong profitability. It is possible, of course, that profitable companies have greater resources available to measure and report financed emissions and corresponding mitigation strategies.

As regulation comes into force and greater disclosures become available, whether this relationship continues to hold will become apparent. However, at present, a commitment to financial decarbonization is certainly compatible with strong financial performance, as well as being predictive of an overall strong ESG approach.

Conclusion

Financial companies across the world will soon be required to provide information on their financed emissions at a level of detail that is difficult to provide and thus far has been rarely attempted. Regulators are focusing on the sector because of its crucial role in delivering a sustainable transition by financing alternatives to the fossil-fueled economy.

Data from the ISS ESG Corporate Rating and ISS EVA products show that for companies in many jurisdictions, there will be a lot of catching up to do to meet these impending requirements. Nevertheless, the cases of jurisdictions with high disclosure, such as the Netherlands and Taiwan, indicate that this is a challenge that companies can meet and that doing so is not in conflict with meeting investors’ financial expectations.

This post comes to us from Institutional Shareholder Services. It is based on the firm’s article, “Ready, Set, Regulation,” dated March 26, 2024, and available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog

As long as China remains the greatest violator and remains unregulated (who is going to tell them what to do?) this entire exercise is nonsense..