Chapter 11 was widely seen as a failure in the first decade of the Bankruptcy Code’s operation, the 1980s. Large firms were mired in bankruptcy for years; the process was seen as expensive, inaccurate, and subject to abuse. While basic bankruptcy still has its critics and few would say it works perfectly, the contrast with bankruptcy today is stark: Bankruptcies that took years in the 1980s take months in the 2020s.

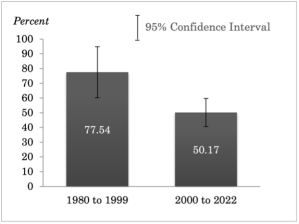

Figure 1. The Decrease in Average Time in Bankruptcy

See underlying paper, linked at the end of this post, for further explanation.

See underlying paper, linked at the end of this post, for further explanation.

Multiple changes explain bankruptcy’s success – creditor learning, statutory reform, better judging and lawyering, new techniques, fuller integration of the improved mechanisms that the 1978 Code added – and we do not challenge their relevance. But in our analysis, one major change is missing from the current understanding of bankruptcy’s success: Bankruptcy courts and practice in the 1980s rejected market value; today bankruptcy courts and practice accept and use market value. This shift is a major explanation for bankruptcy’s success in shortening the process. The shift to market value reduces opportunities for conflict in bankruptcy (although hardly eliminating them). It speeds up proceedings. It allows firms to be repositioned in market transactions. Deals among claimants and interests are more readily reached, and the firm can ride through bankruptcy without the bankruptcy process materially scarring the enterprise.

Foundational to these developments were market-focused changes that came through several bankruptcy channels: (1) courts – which once blocked the sale of whole firms – switched to allow them; (2) judicial doctrine flipped from deeming market value irrelevant to viewing it as presumptively correct; (3) auctions of firms, divisions, and securities directly in market transactions became common, with the bankruptcy judge monitoring the propriety of the sale process without opining directly on the firm’s value; and (4) the surrounding market-based bankruptcy institutions deepened and widened, as more financial firms traded bankrupt firms’ securities or bought and sold the bankrupt firms themselves. The average length of time to resolve large business bankruptcies dropped by 90 percent from the early 1980s to the early 2020s – from three years to three months. We argue that valuation improvements explain much of the increased speed and efficiency of Chapter 11 practice over the decades. We provide evidence that valuation conflicts narrowed and that the corporate reorganization process accelerated.

Figure 2. Narrowing Bankruptcy Valuation Dispute Size Over Time

See underlying paper, linked at the end of this post, for further explanation.

See underlying paper, linked at the end of this post, for further explanation.

True, litigation remains a source of delay and uncertainty, particularly for newly developed controversies like new mass tort bankruptcies, aggressive liability management transactions, and new pre-bankruptcy transactions that generate fraudulent transfer issues. Fairness for nonfinancial creditors remains a source of controversy. But for many, perhaps most, large corporate bankruptcies, especially those with only financial players, the proceedings can be and often are swift. Even counting the new controversies (which induce long bankruptcies when the new controversies are in play), bankruptcy on average now takes about one-tenth the time it took when the statute became law.

What happened?

Bankruptcy courts’ reorientation toward market-based valuation was plausibly central to bankruptcy’s success. True, many new practices emerged through creative adaptation by bankruptcy practitioners and courts, without much in the way of formal amendments to the written statute. Speed-up provisions embedded in the original 1978 Code (like pre-bankruptcy consent to an already-packaged plan and structural aspects like the potential for a debtor-in-possession lender to play a central role and encourage a speedier process) were dormant in the early 1980s, but practitioners and courts eventually learned how to use them. The 2005 amendments limited the debtor’s period of exclusivity to propose a plan and delay resolution. These changes surely helped to speed up business bankruptcy.

In this panoply of change, one change is, in our view, missing from the discussion. Yet it is important and plausibly preeminent: Courts slowly but inexorably turned to market value and to market transactions as increasingly able to deliver more reliable market valuations. The predictability of bankruptcy increased. That increase in predictability plausibly made compromises and deals among creditors easier.

A very brief primer on corporate restructuring and bankruptcy: Distressed firms that cannot keep up with their debt payments typically seek to reduce their debt obligations, often in bankruptcy and sometimes in out-of-court negotiations. Some debts are extinguished, while others are often converted into equity interests in the reorganized business. If the debtor and its creditors cannot come to terms, a bankruptcy court can force a restructuring plan on dissenting creditors.

But to force a nonconsensual restructuring on dissenting creditors, the court must determine that it comports with statutory safeguards meant to protect creditors. The court values the firm to see how much the business can pay back to creditors. It approves distributions to the pre-bankruptcy claimants, but only to the extent that it expects the firm’s value will support those distributions without the firm returning to bankruptcy for another restructuring. The court then confirms a plan distributing that value in accordance with the statute’s priority rules. The highest-ranking creditor is compensated in full before the next-ranking creditor is paid at all, and all creditors are fully paid before stockholders receive any value.

To determine which creditors can participate – by receiving cash, debt claims, equity, or warrants on the reorganized firm – and whether stockholders must be zeroed out, the court must find the firm’s value. Finding that value is challenging; a business’s value – even a non-distressed, nonbankrupt business’ value – is often uncertain and disputed. When the creditors and debtor determine their negotiating positions prior to settling disputes and assenting to a plan of reorganization, they contemplate what the judge will and will not approve. Creditors’ approval and a completed deal depend on what creditors expect the judge will view as the bankrupt debtor’s value.

A shorter bankruptcy is not a goal, in and of itself. It’s a goal because shorter bankruptcies usually arrest the value destruction common in the restructuring process, get firms back on their feet more quickly, and reduce the collateral damage of lost jobs and a degraded workplace. Drawn-out bankruptcies destroy value for investors and stakeholders. Conflicting investor groups expend more resources battling each other in long bankruptcies than in short ones.

This market-based-valuation result has implications for bankruptcy law reform around the world. Several European and Asian nations have looked to Chapter 11 to model their own restructuring laws. We urge caution. Chapter 11 works best in conjunction with institutions that facilitate market valuation and market transactions. The United States developed such institutions only in recent decades; many nations have not developed them yet.

Chapter 11 went from being viewed by many as a deficient legal structure in the 1980s to a substantial success story by the 21stcentury. The switch to market thinking across the bankruptcy spectrum – in bankruptcy transactions, in judging, and in lawyering – goes far in explaining why.

This post comes to us from professors Mark J. Roe at Harvard Law School and Michael Simkovic at the University of Southern California’s Gould School of Law and Marshall School of Business. It is based on their recent article, “Bankruptcy’s Turn to Market Value,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog