The rise of Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) as an alternative pathway to public markets represents one of the most significant features of entrepreneurial ventures in the last few years. Between 2020 and 2021, SPACs accounted for over 40% of companies going public, raising $334 billion in 2021 alone. Yet despite this dramatic growth, empirical evidence on how SPACs affect post-listing governance and performance of firms remains sparse.

In a new working paper, I provide the first large-sample comparative analysis of governance and performance for entrepreneurial ventures that went public via SPACs versus traditional IPOs. In this article, I examine how different routes to public markets create distinct forms of governance that shape the growth of companies.

The procedural differences between SPACs and IPOs create fundamentally different governance. Traditional IPOs involve extensive due diligence by underwriters, auditors, and regulators that typically takes 12-18 months. This process helps create a sound governance structure: boards are expanded with independent directors, specialized committees are established, and founder leadership is often recalibrated to satisfy institutional investors. Venture capitalists, institutional investors, and underwriters act as gatekeepers, vetting firms and ensuring governance meets public market standards.

SPACs follow a different process. They complete their listings in roughly half the time through reverse mergers, bypassing much of the underwriter vetting that characterizes IPOs. The SPACs centers on the incentives of sponsors, who typically receive 20% of shares (the “promote”) upon successful merger completion, regardless of long-term performance. This arrangement creates potential agency conflicts, as sponsors benefit from deal completion rather than post-merger value creation. The accelerated timeline and sponsor-centric structure suggest SPAC firms may enter public markets with less developed governance than their IPO counterparts do.

I focus on 569 SPAC mergers and 1,242 IPOs between 2016 and 2023, using a matched-sample design that pairs each SPAC with IPO firms in the same industry and listing year. This approach controls for industry characteristics and macroeconomic conditions at the time of going public, allowing for cleaner identification of governance differences attributable to the listing mechanism itself.

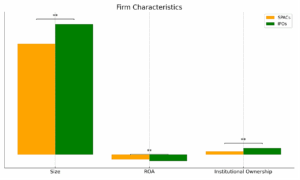

Figure 1: Differences in Firm Characteristics

Figure 1: Differences in Firm Characteristics

The first key result is that there are systematic differences in board composition. SPAC boards are significantly smaller, averaging approximately one fewer director. They exhibit substantially less gender diversity, with 7% fewer female directors, an economically meaningful difference given that the sample mean for female board representation is 23%. SPAC boards also show significantly lower proportions of directors with industry expertise, venture capital or private equity experience, or prior public company board service.

However, SPAC and IPO firms show no statistically significant difference in formal board independence, as determined by the proportion of directors who are not executives of the firm. However, this could simply be a feature of public listing, and the conventional governance measures may obscure more fundamental differences in board expertise, networks, or coordinating capacity. Therefore, I focus on the Blau index as a measure of director-skill overlap, finding that directors on SPAC boards share fewer skills (Blau index of 1.234 versus 0.556 for IPOs), indicating less common ground in directors’ professional backgrounds.

The governance divergence extends to executives. SPAC firms retain founder-CEOs at dramatically higher rates: 79% of SPAC firms versus 48% of IPO firms. CEO turnover rates share this pattern, with SPAC firms experiencing 14% turnover compared with 27% for IPOs, a substantial difference that persists after controlling for firm characteristics, board composition, and institutional ownership.

However, these leadership differences do not translate into different compensation amounts. Total CEO pay levels, and the proportion of equity-based compensation, show no statistically significant differences between SPAC and IPO firms after controlling for size, profitability, and governance characteristics. This suggests the differences in governance derive primarily from the choice and retention of company leaders rather than compensation – a finding consistent with agency-theory predictions that board composition influences monitoring intensity and CEO replacement more than pay levels.

The research shows that the governance differences affect the differences in growth strategies between firms that went public through SPACs and those that went public through IPOs. I provide evidence of how board composition influences firms’ capacity to draw on external resources through alliances and joint ventures.

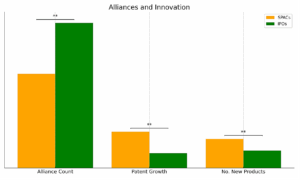

IPO firms form significantly more alliances (8.2 versus 5.3 on average), establish their first alliance sooner (1.2 years versus 1.9 years), and pursue substantially more technology-intensive partnerships (29% versus 17% of alliances). These differences align with theoretical predictions: Boards with directors who possess extensive industry networks and experience forming alliances facilitate the formation of new alliances. Board members’ external connections help reduce the costs of searches for potential partners, provide evidence of their companies’ quality, and enable more rapid alliance formation.

SPAC firms, lacking these network advantages, pursue a fundamentally different scaling strategy centered on internal innovation. They exhibit significantly higher patent-filing rates after going public (2.1 additional patents filed relative to their initial patent stock, compared with 0.8 for IPOs) and announce more new products (1.6 versus 1.0).

Figure 2: Differences in Scaling Pathways

Figure 2: Differences in Scaling Pathways

The innovation effect is strongly moderated by founder presence. SPAC firms retaining founder-CEOs file 1.3 more patents and announce 1.8 more new products compared with SPAC firms that replace their founders – differences that are statistically and economically significant. In contrast, founder presence shows no significant moderating effect on alliance formation for SPAC firms.

These findings contribute to entrepreneurship theory by demonstrating that governance structures established at listing shape the trade-off between the acquisition of resources through alliances and the development of resources through innovation. They also challenge prior research finding that innovation declines after IPOs. SPAC firms, particularly those retaining founders, sustain and even accelerate innovation post-listing, suggesting the differences in governance between IPO and SPAC companies help determine how public markets affect innovation.

The accelerated SPAC timeline and weaker governance structures result in modestly higher compliance costs. SPAC firms exhibit earnings-restatement rates of 15.2% compared with 7.3% for IPOs and report internal control weaknesses at rates of 17.6% versus 7.5%. These differences, while statistically significant, are limited, suggesting governance weaknesses that undermine financial reporting are not so severe as to create wholesale control failures.

Importantly, founder presence does not significantly moderate these compliance outcomes – the effect remains consistent across SPAC firms regardless of CEO identity. This suggests the compliance challenges stem from weaker boards and accelerated listings rather than the management of founders.

Despite concerns about weaker governance, SPAC and IPO firms face statistically indistinguishable litigation risks, with no significant difference in the likelihood of being named defendants. This finding suggests that while SPAC governance can be weaker, that does not translate into more legal exposure in the aggregate.

These findings advance entrepreneurship theory in several ways. First, they demonstrate that how companies go public affects their governance, which shapes their later performance. The choice between SPACs and IPOs is not merely a financing decision but an organizational design choice with lasting consequences for board composition, leadership continuity, and strategic orientation.

Second, the research reveals heterogeneity in how entrepreneurial firms scale after going public. Prior literature has emphasized alliance formation and external resource acquisition as dominant scaling mechanisms, with competent and experienced boards facilitating these tasks. This research identifies an alternative, innovation-led method of growing bigger, one that relies on founders for governance, which may be particularly relevant for technology ventures that depend on sustained R&D investment to create value.

Third, the findings contribute to debates about founder-CEO succession in entrepreneurial firms. While prior research has documented costs of founder retention (including lower financial-reporting quality and sometimes inferior long-term performance), this study identifies the countervailing benefits of sustained innovation. The optimal governance structure depends on whether ventures scale primarily through external partnerships or internal development.

From a practical standpoint, these results suggest entrepreneurs and investors face genuine trade-offs rather than a simple hierarchy of listing quality. The SPACs offers founder retention, faster capital access, and sustained innovation, but at the cost of board expertise, alliance-building, and some compliance quality. IPOs provide professional governance, network access, and stronger compliance, but often require replacing founders and may dampen innovation.

The research opens several avenues for future investigation. First, the matched-sample design, while controlling for industry and timing effects, cannot fully address concerns about which firms choose SPACs versus IPOs. Understanding the determinants of choosing a way to go public –and whether selection effects account for some governance differences – remains important. Recent SEC regulatory changes increasing SPAC disclosure requirements may provide opportunities to study why firms choose the SPAC option. Longer-run studies examining whether governance structures converge over time, and whether initial differences s persist, would help determine how long institutional effects on organizational structure last. Finally, it will be important to examine whether these results can be replicated with firms in different countries.

Swarnodeep Homroy is a professor of finance at University of Southampton and University of Groningen. This article is based on his recent paper, “Exit Routes: Entrepreneurial Governance Imprints and Scaling Paths in SPACs and IPOs,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog