Beginning at least as far back as Professor William Carey’s famously withering 1974 Yale Law Journal article about Delaware’s “enabling” of bad corporate actors, critics of the state’s corporate jurisprudence have alluded to a “race to the bottom” in which the state legislature and judiciary turn a blind eye to managerial agency costs in order to attract new business and maintain Delaware’s dominant franchise in corporate law.

But over the past two decades, a better metaphor for the state’s corporate oversight may be a pinball ricocheting from crisis to crisis, with jurisprudential vigilance varying according to the degree of exigency and fear of federal encroachment.

In the years preceding Enron, WorldCom, and other turn-of-the century shenanigans, Delaware was largely loath to question managerial discretion. After the (first) economic meltdown in 2001, and amid public outcry and federal encroachment via the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, Delaware sought transitory penance, demonstrated most vividly by the Delaware Supreme Court decision that allowed the Disney executive compensation case to be refiled in 2003. Plaintiffs questioned whether Disney’s board acted properly in paying Michael Ovitz $130 million in severance for his brief tenure as the company’s president in 1995, the case having previously been dismissed by Vice Chancellor Donald Parsons. Once the dot-com smoke cleared though, Delaware again became quiescent, with the judiciary making it more difficult for shareholders to prove “bad faith” among fiduciaries in Stone v. Ritter and eventually siding with the board in Disney in 2006.

But soon enough the Financial Crisis arrived, prompting a litany of corporate meltdowns that exposed fiduciary malfeasance and lack of oversight. Again courts cracked down. In In re Citigroup (2009), a case strikingly similar to Disney, Chancellor Parsons refused to dismiss a waste claim involving $68 million in severance paid to Citigroup Chief Executive Charles Prince.

Fast forward to today, nearly a decade since the jurisprudential pinball ricocheted from its last crisis, and Delaware courts have once again reduced their oversight of bad corporate actors. Corwin (2015), for example, substantially undercut the credibility of fiduciary duty litigation and Dell (2017) established a “deal price” presumption in shareholder appraisal actions.

This does not necessarily mean that we’re headed toward another crisis— at least not for a while. Markets have been resilient this year in a volatile political environment and no Enron-level calamity seems imminent. But there are signs of trouble. After Corwin and Dell, company boards and management may feel freer to engage in conflicted and self-interested transactions. One clear indication is the substantial increases in golden parachute compensation and executive compensation generally since Corwin. A subtler sign is the growing trend of CEOs who are “underwater” on their “performance-based” stock awards initiating self-interested change-in-control transactions.

Performance-based share awards only vest if certain performance metrics are met over a defined period. The most common metric is “Relative Total Shareholder Return,” which is a measure of a company’s stock appreciation relative to peers. Performance-based awards can create perverse incentives among underperforming CEOs in the M&A context because changes in control of the company typically trigger vesting of the awards, regardless of the CEO’s performance. As a result, CEOs who are deepest underwater have the biggest incentive to engage in a merger.

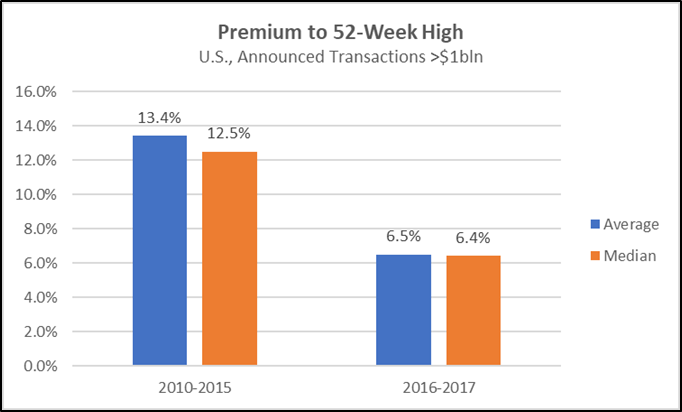

One way to measure this increase in self-interested M&A among underperforming CEOs is with the premium to trailing 52-week high, which is the amount by which a deal price exceeds the highest price of the selling company’s stock during the prior 52 weeks. For example, a company with a trailing 52-week high of $10 per share that is acquired for $12 per share would register a 20 percent premium by this measure. Lower premia to 52-week high would be consistent with more CEOs having underwater stock awards initiating mergers to cash in on those awards, which might otherwise be worthless. The reason that these awards are underwater is that the stocks of the CEOs’ companies have performed poorly. If a company’s shares are already down 20 percent year-over-year, and it is then acquired at a 20 percent premium to market price, shareholders are still net losers, which would be reflected in the 52-week premium measure. As the chart below shows, since Corwin, premia to 52-week highs have nosedived.

Optimists might argue that the courts will become less permissive about managerial self-enrichment. We may know soon enough: Chancellor Bouchard’s upcoming ruling in the Solera appraisal, expected this summer, will be an apt litmus test, as it challenges a 2015 transaction in which Solera Holdings Inc. was acquired at a 6.5 percent discount to its trailing 52-week high. Why sell at a discount? Solera’s then-CEO, Tony Aquila, had a compensation package based on “Total Shareholder Return” and was underwater on most of his options when the deal was struck.

This post comes to us from Matthew Schoenfeld, a portfolio manager at Burford Capital.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog