Of all the conjured hazards faced by the teenage gladiators in the dystopian novel The Hunger Games, the Tracker Jacker (a genetically engineered wasp) was the most deadly and unpredictable when provoked. Dell Technologies Inc. may soon have to contend with its own species of Tracker Jacker, as speculation mounts around the company’s pending offer to its public Class V tracking stock shareholders (NYSE: DVMT)—a cash-and-stock transaction with a claimed valuation of $109 per share. Several activist hedge funds with substantial DVMT positions have vigorously opposed the proposed deal, and their burgeoning resistance has evidently induced Dell to hint at an IPO transaction in the alternative. All the while, the trading price of the Class V shares (hovering currently in the mid-$90s) remains stuck at more than 10 percent below the asserted per-share transaction value. So what gives? In fact, why is Dell dealing with public shareholders at all, after it supposedly went private back in 2013, in a deal sponsored by Silver Lake Partners? And, how does any of this relate to Delaware’s well-known Corwin doctrine hinted at in the title of this post?

These are all good questions, so let’s take them one at a time. First, contrary to popular belief, today’s Dell is a publicly traded company. Or at least a chunk of it is, as a result of its 2016 blockbuster acquisition of EMC Corporation (the former majority shareholder of the high-growth software company VMWare; NYSE: VMW). Pursuant to the terms of that deal, Dell inherited EMC’s public shareholders, converting them into owners of non-voting Dell Class V tracking stock, pegged against the trading value of VMWare (now a majority-owned subsidiary of Dell). Although the DVMT stockholders have no pass-through rights to dividends (which are rarely paid by tech firms anyway), they capture other economic benefits (including capital gains) associated with Dell’s 82 percent ownership of VMWare.

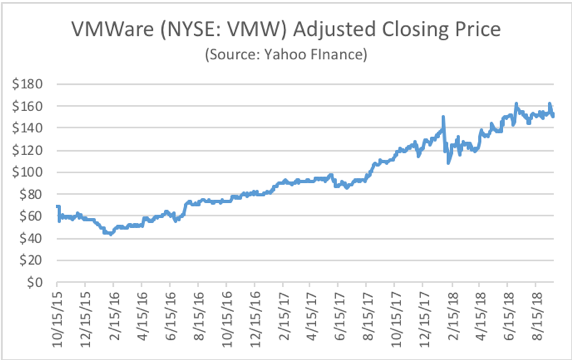

The financial arrangement between Dell and its Class V shareholders has increasingly become a major source of cash-flow consternation for Dell, as VMWare has been on an impressive capital gains winning streak since virtually the day the Dell-EMC deal was announced–tripling in value over the last three years (see figure below). Simply put, VMWare is now Dell’s largest corporate crown jewel. But its dazzling sparkle has largely illuminated the fortunes of DVMT tracker stock alone, leaving the other voting shareholders of Dell with little more than a penumbral afterglow to behold from a distance.

It is therefore hardly surprising that those same shareholders now wish to recapitalize Dell, rearranging its rights and obligations towards DVMT shareholders with the obvious objective of claiming a slice of the VMWare cash flow pie. Executing such a strategy, however, will require Dell to overcome some significant corporate law obstacles pertaining to Michael Dell’s and Silver Lake’s fiduciary obligations. As a dominant shareholder group of the company, they owe fiduciary duties to the totality of Dell shareholders (including holders of DVMT), and thus they would be subject to legal scrutiny under the exacting “entire fairness” doctrine should they foist upon Class V shareholders a self-interested recapitalization. It therefore makes sense that Dell has conditioned its current offer on the recommendation of an independent committee and a majority vote of disinterested DVMT shareholders. Under the now well-known MFW and Corwin line of cases, an informed and uncoerced ratification vote of both an independent committee and disinterested shareholders acts as a strong defense to entire fairness scrutiny, imposing the protective business judgment rule on the action and effectively stopping all shareholder litigation in its tracks.

Although Dell’s special committee was willing to play along with the plan, the Class V shareholders are proving to be a far more cantankerous lot, for at least three reasons. First, even at Dell’s estimated $109 per share, the DVMT shareholders would receive a nearly 30 percent haircut off the current market price of VMWare, the company their stock supposedly tracks. (Although a discount for tracking stock is not unusual, this one appears large by nearly any measure or prior projections.) Aggravating this valuation gap is the fact that Dell induced VMWare to declare a significant and unprecedented $11 billion dividend as part of the DVMT recap, the proceeds of which will flow solely to Dell (which intends to deploy them to finance the cash portion of the transaction). Second, the stock component of the proposed deal—where Class V shareholders would receive 1.3665 Class C shares—reflects a nearly $80-per-share value on Class C stock, which has inferior voting rights. Few believe Dell’s C shares are worth anything near that figure, and even Dell itself valued them at less than half that amount in a tax filing made less than a year ago. While Dell’s recently released revenue projections were notably positive, most observers are skeptical that such forecasts (which curiously include projections for VMWare itself, the benchmark for the tracker) can fully rationalize the stated valuation. Finally, the special committee at Dell charged with negotiating the terms of the proposed recap on behalf of the DVMT shareholders appears to have put up a far weaker fight than its counterpart at VMWare, which had earlier rebuffed a similarly aggressive overture by Dell to acquire the remainder of VMWare itself. Growing shareholder grumpiness has injected considerable uncertainty into the prospects of success for the pending offer to Class V shareholders, inducing Dell to delay its planned public roadshow to shill the deal.

In an interesting strategic move this past weekend, Dell quietly floated the possibility of a conventional IPO of its Class C shares as an alternative to the DVMT recap proposal. One might wonder how an IPO helps Dell, assuming its intent is to onboard the cash flows of VMWare. A public offering of unrelated shares doesn’t change the rights enjoyed by the Class V tracking stock shareholders one iota, right? Not so fast: Under Section 5.2(r) of Dell’s Amended Charter, the company has the right to force a conversion of Class V stock into public Class C stock at an exchange rate pegged against the ratio of the market price of the two classes of shares (adjusted by a premium that depends on how soon after the IPO a conversion occurs). An IPO of Class C stock, therefore, is a necessary prelude to a forced conversion of Class V shareholders sometime down the road.

The IPO-then-convert alternative is a far more perilous path for DVMT holders, due in part to the mammoth unpredictability of the pricing ratio’s realized value once triggered. The market value of DVMT shares (comprising the numerator) has long displayed pricing pathologies of its own, consistently—and controversially—trading at a deep discount to VMWare shares—possibly reflecting Class V shareholders’ squeamishness about their place in the Dell pecking order. And, the market price of Class C shares (the denominator) does not even exist today, with Dell’s projections of its market value careening wildly over the last 10 months (as noted above). Indeed, having spent several months myself grappling with the pricing formula that governs the Class V / Class C share conversion, I am resigned to the conclusion that it is riddled with enough self-referential circularities and indeterminacies to fry the circuits of even the most capable asset pricing algorithm.

And that ultimately brings us back to the impending vote by DVMT shareholders on Dell’s recapitalization proposal. Having contemplated the unsavory prospect of an IPO-conversion just floated by Dell, Class V shareholders may reconsider their opposition and decide that approving the proposed recap is the lesser of two evils. Should that occur and the recap garner a majority vote, Dell will no doubt attempt to leverage its electoral victory into a Kevlar vest protecting it from legal exposure under the MFW and Corwin doctrines.

Such a strategy may work out for Dell, but it carries some appreciable risks. As has been repeatedly recognized both in Corwin and its progeny, for shareholder approval to have its desired cleansing effect, the board must be able to demonstrate that the vote was “fair, uncoerced, and fully informed.” (Corwin, 125 A.3d at 312 n.27; accord Morrison v. Berry, Case No. 445, Del. Supreme Ct. 2017, at 18 n.58.) If the shareholders vote to approve simply “in avoidance of a detriment created by the structure of the transaction the fiduciaries have created, rather than a free choice to accept or reject the proposition voted on” then recent Delaware law dictates that the vote was coerced and thus invalid. (See VC Glasscock’s recent decision in Sciabacucchi v. Liberty Broadband Corporation.) DVMT shareholders could plausibly argue that their affirmative vote was coerced by the unsavory threat of a post-IPO forced conversion. And, while it is true that the underlying “threat” here pertains to the triggering of a provision that was fully disclosed in the Restated Charter, the board is nonetheless required to deploy that weapon in a manner consistent with the fiduciary duties of loyalty, good faith, and candor it owes to the Class V shareholders. In addition, shareholders might also complain that material facts pertaining to either Dell’s or VMWare’s true valuation were not disclosed prior to the vote, which also can render a shareholder vote ineffective as a cleansing device. Finally, this same set of inquiries may also be trained on the actions of the DVMT special committee that approved the deal—whose members were also sitting Dell directors required simultaneously to be faithful to their fiduciary duties specifically to DVMT shareholders.

It is, of course, possible that Dell could still forge ahead, willing to roll the dice under the entire fairness doctrine if necessary. The longstanding discount of DVMT shares relative to VMW, Dell may argue, is a sign that DVMT investors understood the risks of a future conversion. Dell may also marshal some capital-structure arguments, since the DVMT rights appear to be somewhat akin to contingent contractual claims, while the voting Dell shareholders appear to be holding something that represents a more standard residual claim. Emerging Delaware jurisprudence related to venture capital and private equity backed companies suggests that when classes of shares come into conflict, the board is allowed to break ties by pursuing the interests of the residual claimants as owners of “permanent capital.” How far these substantive arguments can be stretched (particularly if confronted by allegations of procedural unfairness) remains hard to predict given the current transitional state of Delaware law on the topic.

Viewed through a dystopian Hunger Games lens, the coming months are likely to reveal some compelling plot lines, not only about the potency of Dell’s Tracker Jacker shareholders, but also about the content and limits of Delaware law itself. It is a showdown that is no doubt worthy of our collective attention. Let the Games Begin (and may the odds be ever in your favor).

This post comes to us from Eric Talley, the Isidor and Seville Sulzbacher Professor of Law and co-director of the Millstein Center for Global Markets and Corporate Ownership at Columbia Law School.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog