The Covid-19 outbreak demonstrates how vulnerable our elaborate cross-border supply chains are to disruption. It isn’t the first time in recent memory that contemporary supply chains have been upended – the 2011 earthquake off the coast of eastern Japan is one of many examples. But Covid-19 has taken supply chain disruption to a new level of severity as well as scale. Failure is no longer measured solely in economic terms; rather, the unavailability of key inputs, from reagents to ventilator parts to personal protective equipment, means the difference between life and death.

How do we begin rebuilding our supply chains in the wake of Covid-19? The starting point, easily overlooked, is a commonplace transactional tool: the preliminary agreement.

The term sheets, memoranda of understanding, and letters of intent that are the bread and butter of corporate transactional practice may seem inconsequential compared with the multi-trillion dollar policies addressing the pandemic. But they’re crucial to reorganizing our supply chains through the negotiation or renegotiation of the deals that knit together those supply chains.

The strategic choices private actors face in managing disrupted supply chains are a subject of well-established research. To crudely summarize, addressing disruptions in a supply chain often involves pursuing a combination of (1) obtaining materials from additional suppliers (more breadth across one’s supply base) and (2) working with existing suppliers to improve reliability (more depth with individual suppliers). Either strategy often involves the negotiation of a contract.

In good times, those negotiations can be fraught with uncertainty. Identifying the best partner in the market is not always straightforward. Supply relationships are often complex, and there are many moving parts in a negotiation to coordinate. Pinning down performance obligations is difficult, especially if the relationship involves innovation. If the relationship involves a unique product or capability, a party may be taken advantage of, because there are few other options in the market.

This is where preliminary agreements play such an important role. By protecting parties’ investment in the bargaining process and addressing additional risks in the negotiation of a complex agreement, preliminary agreements structure risky and unwieldy negotiations, lubricating economic machinery as it adjusts.

But a crisis as profound as the Covid-19 pandemic may require more than standard transactional tools.

The need for innovative new tools grows as Covid-19 knocks out more and more capacity throughout a supply chain. As that happens, the strategy of increasing the breadth of the supply base as a response to disruption becomes that much more difficult. Qualified alternative suppliers are often not waiting in the wings.

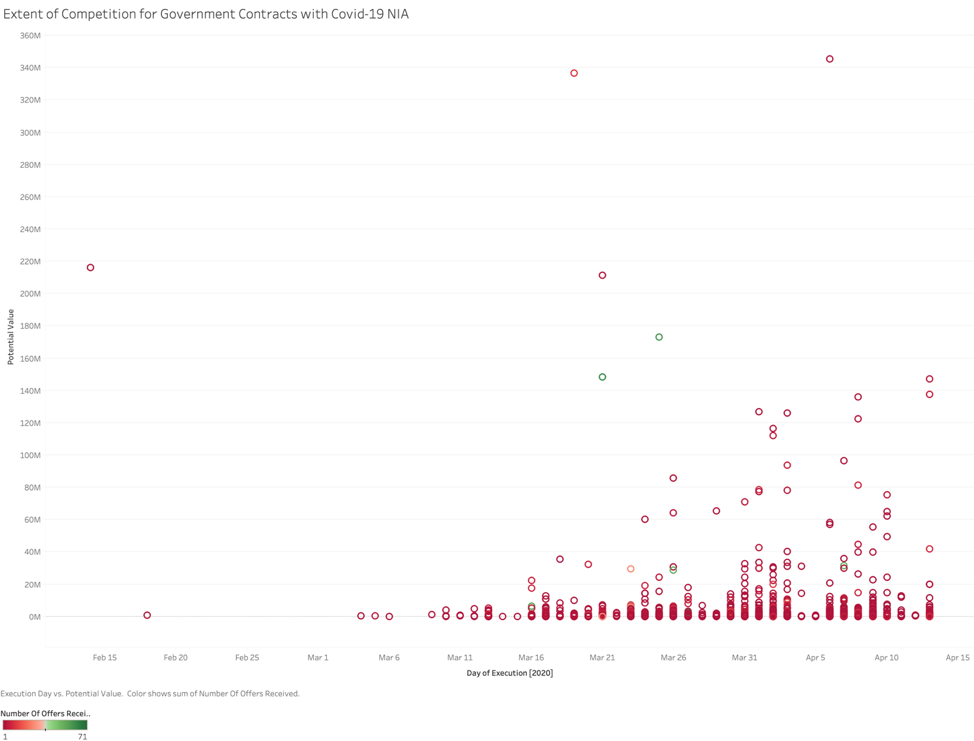

To get a sense of the problem, consider the amount of single/sole sourced contracts the federal government has entered into in the effort to contain Covid-19. Government procurement is often characterized by thin markets, and Covid-19 appears to exacerbate the use of single/sole sourcing. The figure below depicts the 2,643 government contracts that are designated with the “Covid-19” National Interest Action Code in the Federal Procurement Data System. These deals, executed between February 1, 2020 and April 14, 2020, are valued at nearly $60 billion. Each dot in the figure represents a transaction, plotted along the y-axis by its total potential value and along the x-axis by the date of execution. The deals are colored according to the number of competing offers the relevant government agency received in the bidding process, ranging in this dataset from 1 bid (dark red) to 71 (dark green). A handful of outliers were removed to aid visualization.

The prevalence of red in that figure, at both the high and low value ends of the distribution, highlights how common single/sole sourcing has been in the federal response to Covid-19. Of the 2,643 Covid-19 contracts, 1,636 – nearly 62 percent – are single/sole sourced.[1] And of those 1,636 agreements, nearly 39 percent were put out for competitive bidding but only received a single offer. We can only guess at the dynamics in any given deal, but those figures suggest how difficult multi-sourcing can be in the current environment.

Reduced breadth in the supply base puts a premium on efforts to deepen relationships with the suppliers that are available. At the same time, suppliers and customers do not have the luxury of time to build those more interconnected relationships. This is where an innovative approach to the design of preliminary agreements might make a difference.

In an insightful paper, professors Gilson, Sabel, and Scott describe situations where preliminary agreements may be used as tools for structuring an innovation process between parties. The agreements require parties to a contract to share information. That allows them to learn, resolve uncertainty, and deepen their ties to one another at an early stage. In short, preliminary negotiations jump-start early engagement between customer and supplier.

Incidentally, aspects of defense contracting provide an example of parties using preliminary agreements to foster the type of joint-learning process Gilson, Sabel, and Scott describe. In a recent paper, I outline a negotiation process called “alpha contracting,” which has been used by the Department of Defense (“DoD”) from time to time in sole-sourcing situations where significant technological innovation is being pursued.

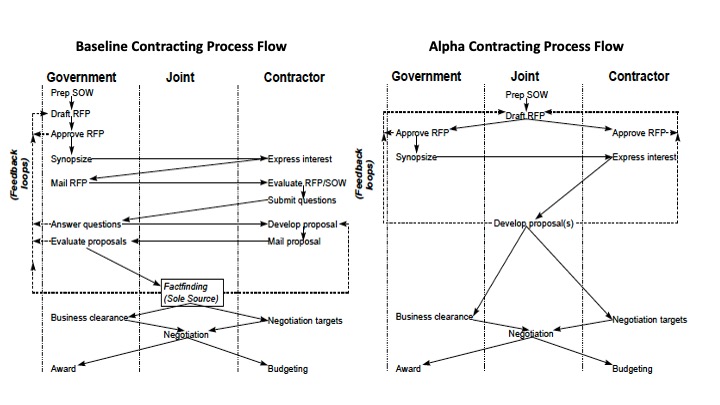

Alpha contracting differs from the traditional arm’s-length sourcing process. In that process the DoD develops a statement of work and requests proposals, suppliers develop offers based on the request for proposals in isolation, the DoD evaluates those offers, and the DoD and a finalist negotiate the details of an agreement. In alpha contracting, the DoD and the prime contractor collaborate on the design of the statement of work and request for proposals, and then jointly develop the prime’s offer. The idea is for the contract negotiations to mirror the engineering process: In many relationships where new technology is being developed, engineering teams from each side often engage early in order to get a jump on joint development. Alpha contracting essentially formalizes those informal interactions.

The result of that early collaboration, which requires the parties to share significant information with one another early, is to blur the boundaries of the negotiation process. The difference between the traditional arm’s length model and the collaborative alpha contracting model is captured in the figures below, taken from a working paper by Mark Nissen at the Naval Postgraduate School.

Additional details on alpha contracting, including the formal governance structures the DoD uses to oversee the process, are described here.

An approach like alpha contracting may not be a silver bullet in every situation — each market is unique, and generalizing from the defense procurement context should be undertaken with care. But the example here is indicative of the type of creative transaction design that is needed to spur innovation processes in supply chains that are in the process of reorganizing themselves. Understanding how these new tools operate should be part of a broader effort to achieve greater resiliency in our global supply chains and are a key piece of the public policy puzzle we face in solving the Covid-19 crisis.

ENDNOTE

[1] For comparison, an analysis of government contract awards related to Hurricane Maria in the FPDS database reveals that only 41 percent of the transactions entered into in response to that crisis were single/sole sourced. Analysis of FPDS data reveals that the percentage of single/sole sourced agreements across all government acquisition programs in a randomly selected month of 2019 (January) for which competitive bidding information is available was 47 percent. Prior research has found a somewhat lower number in U.S. defense procurement, where 33 percent of agreements by value and 22 percent by number are single/sole sourced on average. Mark Pyman, The Extent of Single Sourcing in Defence Procurement and Its Relevance as a Corruption Risk: A First Look, 20 Defence and Peace Economics 215, 223-24 (2009).

This post comes to us from Professor Matthew Jennejohn at Brigham Young University Law School. It is based on his recent paper, “Braided Agreements and New Frontiers for Relational Contract Theory,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog