Is there a simpler – and better – way to predict a recession? The answer is yes, and no, we are not astrologists – though one would not necessarily be wrong to use the position of stars and planets for this purpose. It’s just that we economists prefer economics, and we think you should, too, based on our findings in a recent study, “Predicting U.S. Business Cycle Turning Points Using Real-Time Diffusion Indexes Based on a Large Data Set,” available here. In fact, as we discuss below, using the diffusion indexes we developed in this study, along with some good judgment, one would have successfully predicted the onset of the most recent Great Recession in October 2006. To give a rough idea of how long a lead time this is: The recession started in December 2007 and lasted until June 2009, according to the official declaration on September 20, 2010 from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

So, what is this magical “diffusion index” that enables us to tell the future? Even if you are not an economist, you can understand this without any difficulty. Think of an economic indicator (such as the unemployment rate) as an expert on our economy. Suppose you haul a bunch of them into a conference room and ask them whether the economy is getting better. The percentage of the people in the room saying yes is basically the diffusion index. See, the idea here is very simple, and it makes a lot of sense – provided that people in the room are indeed economists, rather than astrologists who may be very good at their own trade but not necessarily economics. Seriously though, a diffusion index is simply a count – a count of the percentage of relevant economic indicators from a given sample that are increasing over a specified time period. When the count is high, so is the economy.

Unsurprisingly, the idea of diffusion index is hardly new. At least since the 1950s and 1960s, economists have studied the use of a diffusion index. One prominent research paper by Geoffrey Moore from 1950 showed that the historical diffusion indexes led the turns in the business cycle peaks by about eight months. In simple terms, this result means that if you use what you know today to construct a diffusion index, you will be able to tell in advance when a recession happened in the past. If you scream “That’s not a forecast!” you are correct – this result does not directly translate into our ability to foresee a recession. The reason is that economic indicators are usually published well after the fact. For example, based on the data release schedule from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), one would not get the “first final” release of GDP number for this quarter (2016Q3) until December 22, 2016. If you rely exclusively on GDP growth rate to predict recession, you will miss every single time.

Does this mean that a diffusion index is not useful in predicting recessions? This is one of the important questions we attempt to answer in our study. Our approach is essentially to recreate a series of forecasts based on diffusion indexes that we construct in real time. More specifically, we first figure out what information was actually available at the end of each month in the last 30 years. Then, we use this information to make a forecast each month. Knowing what we know today about what actually happened in the last 30 years, we can look at how good the forecasts turned out to be. This way, we can find out if real time diffusion indexes could have delivered good forecasts.

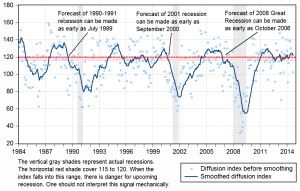

This procedure may sound fairly straightforward, perhaps except the part where we have to figure out what information was available to economists 30 years ago. But in practice, there are several technical issues we have to address. To begin with, we have to make sure we have the proper experts in the conference room and they all understand our question and they all speak English. In technical terms, we want to properly select and transform our economic time series to induce stationarity and homogenize them in terms of their individual cyclicality. This allows us to take the percentage of series that increase each month and construct the diffusion index. But this raw index is very volatile. It moves up and down too much for you or us to see any pattern. So we have to smooth it. Smoothing the index is a delicate matter – too much, you wipe out the lead time and render it useless for forecasting; too little, it remains volatile and difficult to use for forecasting. We consider a few alternative smoothing methods in our study and identify the better ones. One final issue that remains is how you would translate the index, i.e., percentages, into a prediction of whether or not a recession is coming. The graph below shows the raw or unsmoothed index in light blue dots and the smoothed index in a dark blue curve. You can see how difficult forecasting recession would be if the index were not properly smoothed. The light gray vertical shades mark the duration of actual recessions according to the NBER chronology. (We will talk about the red line below.)

To be able to foresee a recession, we must be able to identify a big enough decline in the index. There are three approaches: You could use some simple rule-of-thumb. For example, whenever the index falls below 120 (the red horizontal line in the graph), you say it signals that a recession is just around the corner. Alternatively, you could use a so-called probit regression model, where you feed the index to the model, and the model tells you what the probability of having a recession is in each month. Or, you could do it using a purely judgmental way and simply try to figure out where the turning points are by looking at the graph.

Our finding is that simple rule-of-thumb works fairly well. The three instances where we are able to successfully forecast the onset of a recession are marked in the graph. On average, had we started using this to forecast recession, we would have been able to give warnings of upcoming recessions roughly one year ahead of time. But we may also sound false alarms around 1985 and 1996. In the case of 1985-1986, there was an epic collapse of oil prices. In the case of 1996-1997, we had the Asian financial crisis. While neither resulted in an official recession in the U.S., it is certainly arguable that the risk of recession was high. So, to get high quality forecasts out of the diffusion index, one should also bring some knowledge of the world economy and a bit of good judgment to the process. After all, if predicting recession is something mechanical so that a computer program can do it as well as an economist can, we would most likely be filing for unemployment benefits now.

This post comes to us from Professor Herman Stekler of George Washington University and Professor Yongchen Zhao of Towson University. It is based on their paper, “Predicting U.S. Business Cycle Turning Points Using Real-Time Diffusion Indexes Based on a Large Data Set,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog