Incomplete contracting theories build on the idea that it is either not feasible or too costly for contracting parties such as borrowers and lenders to write contracts that perfectly anticipate all future scenarios. As a result, transacting parties are left exposed to the risk that they might face a costly future renegotiation. This expectation can in turn lead to inefficiencies in terms of investment or other value-enhancing corporate decisions. Despite the widespread use of incomplete contracting theories, few if any empirical studies have directly examined the extent to which future renegotiation considerations affect debt contract structures. My paper contributes to the literature by providing initial evidence about how future renegotiation considerations affect the choice of covenants in syndicated loan agreements.

Investigating the effect of renegotiation costs on contract design in the syndicated loan market is interesting for two reasons. First, this setting offers large variation in terms of expected future renegotiation costs. Private debt contracts can have only one lender or more than 50 of them. Theory and anecdotal evidence suggest that the borrower’s cost to renegotiate a contract increases with the number of creditors. If the loan syndicate comprises only one lender or a small number of lenders, the costs of renegotiating the contract are usually low. For instance, anecdotal evidence suggests that smaller syndicates often waive amendment fees. However, if the syndicate is dispersed, the borrower might find it harder to get approval from a significant majority of lenders without making costly concessions (e.g., higher loan amendment fees) or without experiencing significant delays in getting the contract modified. A second reason why this is a relevant setting is that around 80 percent of all firms use syndicated loan agreements to finance their operations.

My main prediction is that the specific covenant package that contracting parties are willing to agree on varies with the potential costs associated with renegotiating covenants after loan inception. In particular, I predict that when future renegotiation costs are expected to be high, contracting parties will be less likely to include covenants such as capital expenditure covenants, which reduce the borrower’s financial flexibility when the borrower is performing well.

The following example illustrates the basic intuition behind my prediction. Loan contracts often include capital expenditure covenants that specify the type and size of investments that firms can make. Now suppose that the firm is performing well and that an unexpected profitable project arises that can only be achieved if the current loan contract is modified (e.g., because the new investment exceeds the maximum amount allowed under the original agreement). To do so, the borrower will need to convince a significant majority of all lenders (a majority between 67 percent and 100 percent is usually required). If the syndicate is dispersed, the borrower will anticipate a higher probability of a costly renegotiation in the form of higher loan amendment fees, delays in the approval of contract modifications, or, in an extreme case, the risk of not getting the modification approved. This situation, in turn, will lead to inefficiencies because the borrower will not have the proper ex ante incentives to pursue this type of profitable investment opportunity. Therefore, using the number of lenders as my proxy for renegotiation costs, I hypothesize that when renegotiation is more costly (i.e., when the number of lenders is large), the contracting parties will exclude covenants that restrict investments or other important corporate policies in good states.

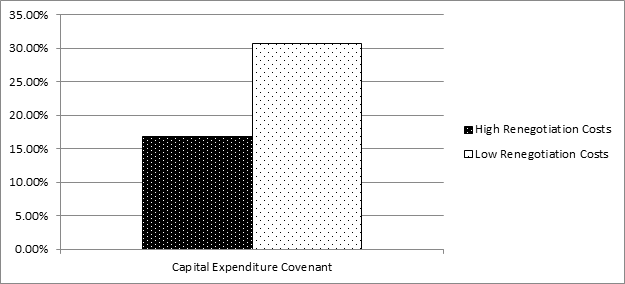

Using a sample of 11,956 loan deals originated between 1995 and 2012, I find that when future renegotiation costs are expected to be high, debt contracts are less likely to include capital expenditure covenants. For instance, Figure 1 provides simple univariate evidence about how the likelihood of including a capital expenditure covenant varies with renegotiation costs. The graph shows that when renegotiation costs are high (i.e., when the number of lenders is above the sample median), only 17% of the debt contracts include a capital expenditure covenant. In contrast, when renegotiation costs are low (i.e., when the number of lenders is below the sample median), 31% of the debt contracts include a capital expenditure covenant. Overall, these results are consistent with my hypothesis that future renegotiation costs are an important determinant of how contracts are written and covenants are selected.

Figure 1: Renegotiation Costs and Capital Expenditure Covenants. This figure presents evidence regarding the percentage of syndicated loan contracts that include a capital expenditure covenant as a function of renegotiation costs.

I also conduct cross-sectional tests based on variables that proxy for firms’ ability to access alternative sources of financing. Renegotiation concerns should be particularly severe if the borrower has few outside options and cannot easily switch to other lenders at the renegotiation stage. Thus, I predict that the effect of renegotiation on covenant choices is going to be stronger for the sample of borrowers that are more likely to face a costly future renegotiation. Consistent with this prediction, the negative relation between renegotiation costs and capital expenditure covenants is stronger when the borrower (1) has assets that cannot be used as collateral, (2) has a credit rating below investment grade, and (3) is small.

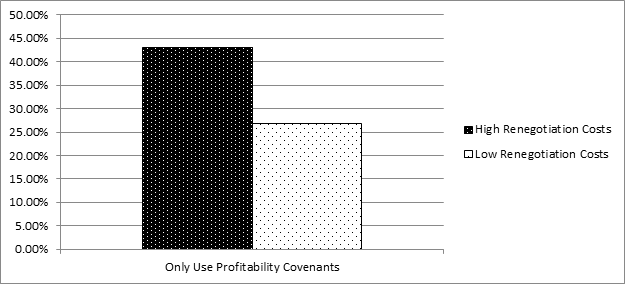

Finally, I investigate whether lenders, in exchange for giving the borrower more flexibility in good states, demand more covenants that are timelier in transferring decision rights to the lenders in bad states (i.e., when the borrower is close to default). Consistent with this intuition, I find that when renegotiation costs are high, contracts are more likely to only rely on covenants that are directly linked to the current performance or changes in the credit risk of the borrower. For instance, Figure 2 provides univariate evidence about how the likelihood of only contracting on profitability covenants varies with renegotiation costs. The graph shows that when renegotiation costs are high (i.e., when the number of lenders is above the sample median), 43% of the debt contracts only use covenants that are directly linked to the profitability of the borrower. In contrast, when renegotiation costs are low (i.e., when the number of lenders is below the sample median), this number drops to 27%. Overall, these results suggest that when future renegotiation costs are expected to be high, debt contracts use covenants that are directly linked to the current performance of the borrower, which allows for a more efficient allocation of decision rights between the borrower and lenders.

Figure 2. Renegotiation Costs and Profitability Covenants. This figure presents evidence regarding the percentage of syndicated loan contracts that only use profitability covenants as a function of renegotiation costs.

This study makes two primary contributions. First, I provide initial evidence that future renegotiation and incomplete contract considerations are an important determinant of how covenant packages in debt contracts are written. I find that when future renegotiation costs are expected to be high, contracting parties will anticipate this and not contract on covenants that limit firms’ financial flexibility in good states. In addition, the findings in my study suggest that contracting parties adjust the contract ex-ante to minimize ex-post renegotiation costs. More specifically, the choice of covenants in the original contract does not stave off costly renegotiation but rather allocates bargaining power to either the borrower or lender in different states of the world. As a result, my paper provides a rationale for the findings in the literature that syndicated loan contracts are often renegotiated before their maturity. Second, my study contributes to a better understanding for why specific covenants are used in debt contracts. To date, the fundamental forces that explain the cross-sectional variation in the use of different covenants in debt agreements remain largely unexplored. My study contributes to this literature by showing that the selection of covenants is significantly determined by future renegotiation considerations.

The preceding post comes to us from Daniel Saavedra, Assistant Professor at the UCLA Anderson School of Management. It is based on his recent article, which is entitled “Renegotiation and the Choice of Covenants in Debt Contracts” and available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog