“Culture, more than rule books, determines how an organization behaves.” – Warren Buffet[1]

In recent years, there have been ongoing occurrences of serious professional misbehavior, ethical lapses and compliance failures at financial institutions. It was the crisis that exposed systematic mentality errors in finance.[2]

The hope was that post-crisis regulatory reforms would tackle the typical mindset of short-term oriented self-enrichment in finance, considered as one of the origins of the financial crisis. Now, almost ten years after the crash in 2007, the lack of fundamental change raises the question whether there is an endemic issue within the financial sector.

Central Banks and other regulators take the initiative

There is a consensus that the financial sector’s culture needs to change and reorient from individualistic self-servicing, to a more client and shareholder focused business approach. The initiative for this shift has not come from the financial services industry, but rather from the regulatory authorities. That, by itself, is a governance failure. While compliance has become overburdening, no financial institution has looked at the critical element of their behavior: culture.

The initiative to address culture started in the UK where Clive Anderson, Director of Supervision at the Financial Conduct Authority recognizes the public’s post-crisis skepticism towards the financial sector. “It is fair to say that to many in the outside world, the cultural approach of doing the right thing has been lost for financial services. It is clear to us, therefore, particularly as a conduct regulator, that the cultural characteristics of a firm are a key driver of potentially poor behaviour and I would like to explore this further with you today.”[3]

The US Federal Reserve through the voice of the New York Fed’s president talked about the need to reconsider “firm values, business strategy, and actual behaviors.” In the words of Bill Dudley: “A bank’s culture must promote decisions and behavior that take into account the firm’s many stakeholders, including the public, because of the special role that banks play in the economy. [4]

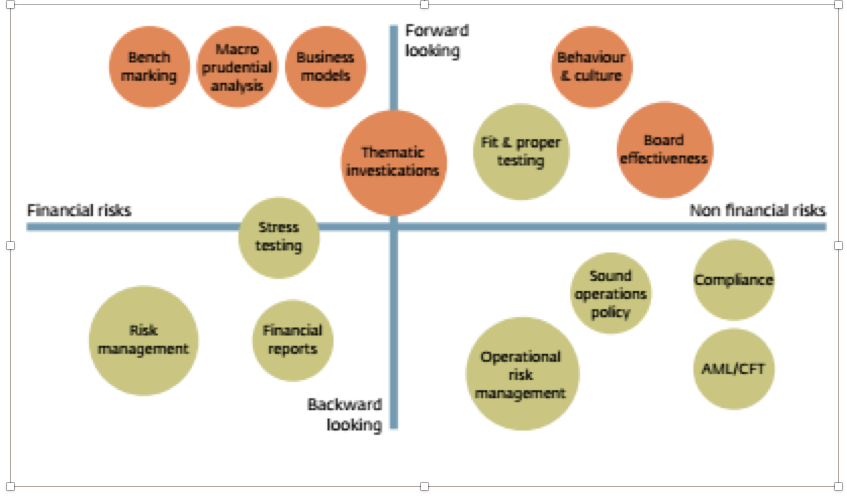

Because regulators are leading the call for awareness and change of culture, they might not spearhead the cultural reform beyond intensifying the focus on regulatory compliance. This allows financial institutions to limit their cultural change to strict rule following – which is in itself demanding. De Nederlandsche Bank, the Dutch Central Bank, extensively examined the supervision of behaviour and culture of the financial sector, considering these among the forward looking non-financial risks.[5]

It is, however, from within the firms that cultural changes have to happen. The irony about corporate culture is that whereas culture only emerges and grows from within the firm, outsiders will identify and challenge it. That makes culture a leadership challenge.

There is no hard-boiled evidence that culture is important. Yet financial services executives frequently informally acknowledge a “very strong culture” that they recognize and respect. Indeed, the UK’s FCA finds: “Culture drives individual behaviours, which in turn affect day-to-day practices in firms and their interaction with customers and other market participants. Culture is therefore both a key driver, and potential mitigant, of conduct risk. The experience of the past demonstrates that a poor culture can lead to poor outcomes for consumers and markets.”[6]

What makes a culture?

Culture is an elusive concept as every firm has its unique culture (or lack thereof) and a myriad of factors constitute a culture. To make culture more tangible, there are a few elements for firms to bear in mind when building an idiosyncratic culture from within the firm.[7] Four simple ingredients of a corporate culture that are not only specific to the financial services industry are:

- Vision: Without an explicit vision of the purpose of a financial institution that will drive strategic decisions, there is no foundation to culture. Vision, in the financial services, is focused on the added value the institution brings to its clients, employees, shareholders and community. Firms should ask themselves: “What does my institution bring to our clients?”

- Values: There is no culture without an explicit reference to the values of the institution.[8] All companies have their values spelled out in their mission statement, but values have to be actionable. There is a deep need for candor and authenticity in this definition.

- Role models: How are the vision and the values implemented in the day-to-day life of a financial institution? One of the greatest gaps of credibility of the culture is the distance between acts and talks. Board members and management have often “delegated” these issues to their lower levels. Refusal to assume responsibility for mistakes is probably the most important deterrent to the confidence in bankers. The G30 recommends boards ensure oversight of the adoption and application of values, to be translated in subsequent behavior. It is primariy the responsibility of the CEO and executive team to guarantee that the “tone from the top” consistently resonates as an “echo from the bottom”.[9]

- People: It is one thing to state vision and values, it is another to convince people that it will be coherently exercised inside the company. Empowering every management level to implement human resources policies, from recruiting to promotion and sanctions, is critical. No company can build a coherent culture without people who either share its core values or possess the willingness and ability to embrace those values.

Should conduct derive from explicit cultural values?

By putting conduct and culture together, authorities might have thought that they go hand in hand. The relationship between conduct, compliance and culture is however complex. Culture should be a set of values that is considered to be the backbone of an institution and co-defines its job environment. Culture should drive conduct; where compliance is only a part of what constitutes conduct. FINRA recognizes the importance of culture where it seeks to understand how culture can affect compliance and risk management at firms.[10]

Most responses to this initiative have translated themselves into “codes of conduct”, a legal jargon that might be useful for compliance purposes but uninspiring and restrictive as regards to culture. A few examples:

- Société Générale’s code of conduct is compliance-driven but stresses the value of client relationships. SocGen “intends to establish itself as the benchmark in relationship banking, chosen for the quality and commitment of its staff in supporting the financing of the economy and its clients’ plans.”[11]

- Citi talks about “value proposition” where its mission is to serve as a trusted partner to its clients by responsibly providing financial services that enable growth and economic progress. We strive to earn and maintain the public’s trust by constantly adhering to the highest ethical standards. Our managers have a responsibility to lead by example.[12]

- Barclays says it strives “to create and maintain mutually beneficial long-standing relationships with personal, business, institutional and international customers and clients that meet their needs and exceed their expectations.”[13]

- JP Morgan’s code of conduct talks about its “people, our services and our enduring commitment to integrity have made us one of the largest and most respected financial institutions in the world. We all share responsibility for preserving and building on this proud heritage.”[14]

The question is what happens when these laudable ambitions are well articulated in a text file – and stay there. Financial firms, despite regulatory pressure, have been able to escape serious scrutiny of their lack of cultural change. Why? Because many perceived the financial sector as a whole tainted by a corrosive culture: a lack of culture, or commitments beyond pecuniary maximization, has become synonymous with being in finance. The lack of culture is so pervasive, or at least so entrenched, that even those with values beyond the bottom line may be embarrassed to show their leanings let alone proselytize. That and culture is difficult to measure. Industry-wide, firm-specific, divisional and individual shortcomings are imperceptible due to the lack of contrast and unit.

Financial services and fiduciary responsibility

Recently John C. Coffee Jr. published an interesting blog on how to address a culture of silence within a firm regarding the corporation’s illegal practices, based off the Volkswagen case regarding the installment of its “defeat device”.[15] Professor Coffee convincingly explains how Volkswagen executives could rely on employees to collaborate – the firm’s culture of silence effectively enabled fraud. Where culture and conduct is an issue in big corporates in general, finance has its unique relation to culture. This is reflected in the fiduciary duty: based on “fides”, Latin for “good faith”. It is a core asset of financial institutions comprised of confidence and trust. The focus on culture in financial institutions – besides the problems of other corporates – is due to the fact that, additionally to accountability to shareholders, banks can only operate by using resources that are granted to them on a fiduciary basis. Even though the financial crisis lies almost a decade behind us, the question is still whether most executives in finance think and act as good faith-inspired custodians of other peoples’ money.

How can a fiduciary culture inspire confidence and trust in finance? If, and only if, those who entrust their assets to banks are convinced that the use of those funds will be dedicated to prudent and productive purposes. The President of the Fed New York is explicit on the specifics of the industry.

Although cultural and ethical problems are not unique to the finance industry, financial firms are different from other firms in important ways. First, the financial sector plays a key public role in allocating scarce capital and exerting market discipline throughout a complex, global economy. For the economy to achieve its long-term growth potential, we need a sound and vibrant financial sector. Financial firms exist, in part, to benefit the public, not simply their shareholders, employees and corporate clients. Unless the financial industry can rebuild the public trust, it cannot effectively perform its essential functions. For this reason alone, the industry must do much better.[16]

The crucial role of governance in culture. Does the top really buy in?

The Group of Thirty (“G30”) that comprises former central bankers has been acting for decades as a think tank on delicate issues affecting the world of finance.

Executive Committees and Boards have generally been vocal about culture and values. However, the behavior of executives and employees is neither challenged nor even monitored. Even after the financial crisis, there have been numerous cases of fraud that left an impression that behaviors might not have evolved positively.

The culture of firms and the people that make them up – and of course therefore the culture of industries insofar as it can be generalised – is of the utmost importance to financial regulators. Culture matters a great deal. And this is true for both conduct and prudential regulators. My assessment of recent history is that there has not been a case of a major prudential or conduct failing in a firm which did not have among its root causes a failure of culture as manifested in governance, remuneration, risk management or tone from the top. [17]

How do you change a culture?

Compliance will never change a culture. At best it will create boundaries for behavior that will limit the scope and rights pertaining to the financial institution and its executives. Steve Denning, a financier who is now one of the authorities in leadership and organisational change summarizes his methodology the following way:

- Do come with a clear vision of where you want the organization to go and promulgate that vision rapidly and forcefully with leadership storytelling.

- Do identify the core stakeholders of the new vision and drive the organization to be continuously and systematically responsive to those stakeholders.

- Do define the role of managers as enablers of self-organizing teams and draw on the full capabilities of the talented staff.

- Do quickly develop and put in place new systems and processes that support and reinforce this vision of the future, drawing on the practices of dynamic linking.

- Do introduce and consistently reinforce the values of radical transparency and continuous improvement.

- Do communicate horizontally in conversations and stories, not through top-down commands.

- Don’t start by reorganizing. First clarify the vision and put in place the management roles and systems that will reinforce the vision.[18]

The complexity of cultural change cannot be underestimated. It requires senior management initiatives, executive and staff buy-in, explicit vision and values, governance adjustment, and, more importantly, a culture that deeply respects clients and other stakeholders.

It is however an indispensable undertaking and I would go as far as stating that successful financial institutions will need to reach a level of excellence in developing and implementing this vision.

ENDNOTES

[1] See Warren Buffet, “Memorandum to the Berkshire Hathaway Managers”, The Financial Times, September 27, 2006, online at http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/48312832-57d4-11db-be9f-0000779e2340.html#axzz4CnAXOkMH.

[2] See Gary Silverman, “Bring on the Revolution in Banking Culture”, The Financial Times, July 24, 2015, online at http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/a4b5883e-316c-11e5-91ac-a5e17d9b4cff.html?siteedition=uk&iab=barrier-app#axzz4CnAXOkMH.

[3] See Clive Adamson, “The importance of culture in driving behaviours of firms and how the FCA will assess this”, Financial Conduct Authority, April 19, 2013, online at http://www.fca.org.uk/news/regulation-professionalism.

[4] See Bill Dudley, “Reforming Culture and Behavior in the Financial Service Industry: Workshop on Progress and Challenges”, New York Fed, November 15, 2015, online at https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/newsevents/events/banking/2015/culture_workshop_summary_2015.pdf.

[5] See De Nederlandsche Bank, “Supervision of Behaviour and Culture, Foundations, practice & future developments”, 2015, online at http://www.dnb.nl/binaries/Supervision%20of%20Behaviour%20and%20Culture_tcm46-334417.pdf.

[6] See Financial Conduct Authority, “Culture in Banking”, 2015, online at https://www.fca.org.uk/static/documents/foi/foi4350-information-provided.pdf.

[7] See John Coleman. “Six components of a great corporate culture”, Harvard Business Review, May 2013, online at https://hbr.org/2013/05/six-components-of-culture.

[8] See G30, “Banking Conduct and Culture, A Call for Sustained and Comprehensive Reform”, July 2015, p. 12, online at http://group30.org/images/uploads/publications/G30_BankingConductandCulture.pdf

[9] See G30, “Banking Conduct and Culture, A Call for Sustained and Comprehensive Reform”, July 2015, p. 13, online at http://group30.org/images/uploads/publications/G30_BankingConductandCulture.pdf.

[10] See FINRA, “Regulatory and Examination priorities letter”, January 5, 2016, p.1, online at http://www.finra.org/sites/default/files/2016-regulatory-and-examination-priorities-letter.pdf.

[11] See Société Générale, “Group Code of Conduct”, 2013, online at https://www.societegenerale.com/sites/default/files/documents/Group%20Code%20of%20conduct_UK_2013.pdf.

[12] See Citigroup, “Mission and Value Proposition”, online at http://www.citigroup.com/citi/about/mission-and-value-proposition.html.

[13] See Barclays, “The Barclays Way – How we do business”, July 23, 2015, online at https://www.home.barclays/content/dam/barclayspublic/docs/AboutUs/Purpose-Values/BAR_TheBarclaysWay%20cropped%2023_07_2015.pdf.

[14] See JP Morgan Chase, “Code of Conduct – Integrity: it starts with you”, 2012, online at https://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/About-JPMC/document/2012_CodeofConduct.pdf.

[15] See John C. Coffee, Jr., “Volkswagen and the Culture of Silence”, CLS Blue Sky Blog, May 23, 2016, online at http://clsbluesky.law.columbia.edu/2016/05/23/volkswagen-and-the-culture-of-silence/.

[16] See William C. Dudley, “Enhancing Financial Stability by Improving Culture in the Financial Services Industry”, New York Fed, October 20, 2014, online at https://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2014/dud141020a.html.

[17] See Andrew Bailey, “Culture in Financial Services – A Regulator’s Perspective”, Bank of England, May 9, 2016, online at http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/speeches/2016/901.aspx.

[18] See Steve Denning, “How Do You Change An Organizational Culture”, Forbes, July 23, 2011, online at http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2011/07/23/how-do-you-change-an-organizational-culture/#75f1bc703baa.

The preceding post comes to us from Georges Ugeux, a Lecturer in Law at Columbia Law School and Chairman and CEO of Galileo Global Advisors.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog

Should this/can this? be applied to education/children services. where the policy/culture produce very limited value to both the client and the community at large. Thank you for your time.

Indeed, Joe.

While this article is focused on financial services, where it becomes part of regulation, There is a societal trend to focus on one self (institutionally or personally) rather than having a focus on those we are supposed to serve.