Throughout the 1990s, the Big 5 accounting firms made a concerted effort to enter the legal services market. By the close of the twentieth century, legal networks directly owned or closely affiliated with the Big 5 were major players in many markets around the world, and were threatening to enter those like the United States from which they were still barred. However, after the wave of accounting scandals arising out of the 2001 financial crises—scandals that brought down Arthur Andersen and ushered in regulatory reforms in the United States and other major economies that appeared to place severe restrictions on the ability of the now Big 4’s ability to offer non-auditing services to their audit clients—most observers concluded that the accounting firms’ legal networks were effectively dead. As a result, both practitioners and academics stopped paying attention to what these firms were doing in law.

Our research, however, points to a quite different conclusion. In a recently published article in Law & Social Inquiry, available here, we employ a unique data set comprised of information collected from the corporate websites of the Big 4 and their affiliated or strategic partner law firms, as well as archival material accessible from the legal and accountancy press, to demonstrate, as Mark Twain might say, that the reports of the death of the Big 4’s legal ambitions have been greatly exaggerated. (For more information about this research, see “The Reemergence of the Big Four in Law,” The Practice Volume 3, Issue 2, available here). In this Post we summarize our findings.

Hiding in Plain Sight

In the immediate aftermath of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the Big 4 appeared to confirm that they had abandoned their efforts to become important players in the market for legal services, publicly declaring that they were unwinding their legal networks. Notwithstanding these public pronouncements and some initial actions to disband their legal arms, however, over the last decade the Big 4 have quietly rebuilt their legal networks to the point where they are now larger than they were in 2002. As Figure 1 documents, by May 2016, PwC had established legal practices in 85 countries worldwide and KPMG in 53 countries, while Deloitte and EY each had legal practices in 73 countries. Taken together, a total of 106 countries are currently hosting at least one of the Big 4’s legal practices, giving them a significant presence in every important legal market in the world with the notable exception of the United States.

Figure 1.

The Big 4’s Legal Practice Worldwide

Countries where any of the Big 4 had established a legal practice by May 2016

The Big 4’s Legal Practice Network

% of countries where the Big 4 have a legal practice

Nor are the legal services delivered by these networks confined to tax. Although tax-related advisory services remain an important cornerstone, the Big 4 legal networks are now delivering services in a broad range of legal fields, including premium practices such as finance and M&A, and fast growing ones such as compliance and employment law. The success of this strategy is evident from the growth in size, profitability, and prestige of the Big 4’s legal networks in recent years. In France, Spain, Italy, and Russia, for example, law firm rankings now put the Big 4’s legal practices in the top 10 in terms of revenue. In Germany and the UK, the Big 4 are showing double-digit annual revenue growth. The Big 4’s progress in emerging markets is even more impressive. In 2015, for example, EY Law’s network firm in China – EY Chen & Co. – was ranked in the top third for “Eminent Performance” in capital-market related legal services. That same year, PDS Legal – EY’s law network firm in India – was ranked among the top-10 advisors in completed M&A deals.

To support this expansion, the Big 4 have returned to the kind of lateral recruiting of star lawyers not seen since the 1990s, luring top lawyers away from leading law firms such as Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, Linklaters, and King & Wood Mallesons. As impressive as this lateral hiring spree is, however, the fact that the global leaders of the Big 4’s legal networks have all grown up inside these organizations underscores their strong commitment to integrating these practices into the broader culture and practices of their global multidisciplinary network. To accomplish this goal, KPMG, EY, and Deloitte have followed PwC’s lead of integrating their “independent” law firm partners into their umbrella networks. For example, since 2012, Deloitte initiated the process of fully integrating its German strategic partner, Raupach & Wollert-Elmendorff Rechtsanwaltsgesellschaft mbH, into the Deloitte network – now rebranded Deloitte Legal Rechtsanwaltsgesellschaft mbH – as well as rebranding its Canadian affiliated law firm, Heddema & Partners LLP, to Deloitte Tax Law LLP.

Finally, and most important, beginning in January 2014 PwC, KPMG, and EY have all filed applications to launch an “Alternative Business Structure” (ABS) that will allow them to provide legal services in the UK under the new law that allows for organizations not exclusively owned and controlled by lawyers to deliver legal services. Significantly, two of the three – EY and KPMG – have now been granted a license to become a “multidisciplinary professional service firm,” under which they are now entitled to provide a mix of legal and non-legal” services to clients.

More than a decade after they were proclaimed dead by most pundits – the Big 4’s increasingly integrated and expansive legal networks are alive and well in the global market for legal services.

How Did this Happen?

Looking back, we believe that four interrelated factors have allowed the Big 4 accounting firms to expand their legal offerings notwithstanding efforts to prevent them from doing so. First, while Sarbanes–Oxley and other related statutes severely restrict the Big 4’s ability to sell non-audit services, these laws do not prohibit them from the legal market altogether. While accounting firms are barred from selling legal and other non-audit services to their audit clients, nothing prevents them from marketing such services to non-audit clients, which they all now aggressively do. Second, combined with this important gap in the regulation of auditor independence, as the UK reforms cited above underscore, the regulation of the legal profession has become increasingly open to entities not owned or controlled solely by lawyers providing legal services. The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) with its emphasis on encouraging the free flow of professional services has only reinforced this trend. As a result, the kind of multidisciplinary practice championed by the Big 4 is now expressly legal in many major legal markets, most importantly in the UK. At the same time, the Big 4 have been able to exploit loopholes in the regulation of the legal profession in emerging economies where this regulatory framework is far less developed than it is in the West to establish their legal practices.

This last development underscores the third factor that has allowed the Big 4 to reemerge as important players in law: globalization. As multinational companies have rapidly expanded their operations around the globe, they have increasingly looked for professional service firms that can provide these sophisticated entities with consistent services—including legal services—across their entire platform. Given their extensive experience in marshaling global resources, the Big 4 are in an ideal position to meet this need. This is particularly true in the rapidly growing emerging markets in Asia, Latin America, and Africa, where few law firms can credibly claim to provide comprehensive service – and those that claim to have this capacity often do so through a set of loosely affiliated offices. Although the Big 4 were the first to pioneer this Verein structure, the accountancy networks have taken concerted steps over the last two decades to move away from this structure in favor of one that emphasizes greater integration of their multidisciplinary practices. This evolution of the Big 4’s business model constitutes the fourth – and potentially the most important – reason for their reemergence as significant players in the market for legal services, one that could hold the key to their long-term success this time around.

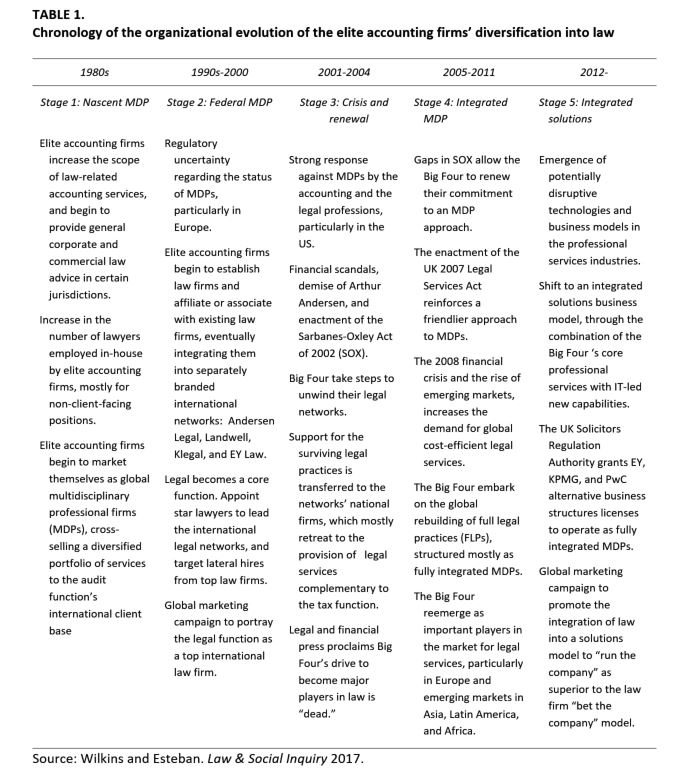

It has taken decades for the Big 4 to elaborate their MDP structure into a robust organizational model. Table 1 elaborates this evolution from a “nascent MDP model” in the 1980s, where the Big 4 first began to build up their legal capacity to sell to their existing audit clients, to the fully “integrated solutions model” they purport to use today, which is designed to leverage their strong capabilities in information technology, process management, and their global reach to provide “globally integrated business solutions” to global clients – with legal services bundled as part of the global solution.

To be sure, the promise of fully integrated business solutions may still be more rhetoric than reality. Nevertheless, it is a promise that is likely to appeal to companies who have been seeking lawyers who “understand the company’s business” in the years following the global financial crisis. Similarly, the Big 4’s promise of providing a better model of professional development is also likely to appeal to many young lawyers who have become disenchanted with what they perceive as the oppressive environment of many large law firms. As just one example of the power of this message, for two years in a row Deloitte Legal was recognized as the most attractive law firm employer by Czech law students.But the greatest force propelling the Big 4’s integrated solutions model may be their embrace of technology. Deloitte’s investments over the past several years in this area are illustrative of this trend. In 2014, Deloitte purchased ATD Legal, one of the few providers of managed document review services in Canada. In 2016, they followed with a purchase of Conduit Law, a provider of outsourced lawyers ranked by the Financial Times as one of the “Most Innovative North American Law Firms.” Most recently, Deloitte formed a strategic alliance with Kira Systems, which has been described by the company’s chief executive, Noah Waisberg, as “the largest professional services AI [artificial intelligence] deployment anywhere, period.”PwC’s recently announced partnership with General Electric provides one example of what a managed legal services future might look like. In 2017, PwC signed an agreement with GE to provide integrated, enterprise managed tax services on a global basis for a five year period. As part of the deal, PwC agreed to hire more than 600 members of GE’s tax team, including many lawyers. PwC announced that these individuals will not only service GE, but will also be available for other clients.To be sure, most of the tax work that PwC will be doing for GE would not be considered premium by the tax departments of most top law firms. But as the global head of one of the Big 4’s legal arms underscored, their goal is not to concentrate on “bet the company” cases, as most large law firms obsessively do, but instead on “run the company” cases. Such a strategy will give the Big 4 a seat at the table as companies strive to rein in the cost of providing legal and other related services in the new global age of more for less.The Future?Whether these and other similar moves by the Big 4 will enable these newly energized players to significantly disrupt the market for corporate legal services remains to be seen. Important obstacles ranging from potential conflicts of interest, to regulatory backlash, to internal resistance in companies to relying too heavily on a single professional service provider could yet again derail the Big 4’s ambitious plans. For now, we simply conclude by urging that academics and practitioners pay greater attention to how these important players are attempting to redraw the boundaries of professional services, and to how law firms, clients, and regulators respond to the potentially disruptive, but still largely unexplored, changes that the Big 4 are bringing to the global legal services market.

This post comes to us from David B. Wilkins, the Lester Kissel Professor of Law, Vice Dean for Global Initiatives on the Legal Profession, and Faculty Director of the Center on the Legal Profession at Harvard Law School, and from Maria J. Esteban Ferrer, a lecturer in the Department of Law at ESADE, Univrsitat Ramon Llull, affiliated researcher at the Harvard Law School Center on the Legal Profession, and Co-Director of the Center’s Big 4 Research Project. The post is based on their recent article, “The Integration of Law into Global Business Solutions: The Rise, Transformation, and Potential Future of the Big Four Accountancy Networks in the Global Legal Services Market,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog