In recent years, there has been considerable criticism of the amount of money that CEOs earn to run the largest U.S. companies. Governance researchers have expended considerable resources examining executive compensation in an effort to determine whether pay levels are set fairly. The results of these studies are generally mixed.

An important and related question, however, is rarely asked: Just how scarce is CEO talent? How many people are very well qualified to run a large, publicly traded company? These questions have important implications for CEO pay levels, performance measurement, succession planning, and internal talent development.

CEO Talent Pool

Recently, Stanford Graduate School of Business and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University conducted a survey of directors currently serving on the boards of the largest 250 U.S. companies by revenue (Fortune 250) to better understand their perspective on the size and quality of the labor market for CEO talent.1

The perspectives of corporate directors are critical for understanding the depth and quality of the CEO labor market because directors are highly knowledgeable about the number, quality, and performance of top talent in their industry, and through their regular succession planning discussions should have identified specific individuals or candidate pools to turn to in a transition.

The survey finds that directors overwhelmingly believe that the CEO job is very difficult and that only a handful of executives are qualified to run companies in their industry. Almost all directors (98 percent) describe the CEO job at their company as extremely or very challenging. Practically none (2 percent) believe it is moderately, slightly, or not at all challenging.

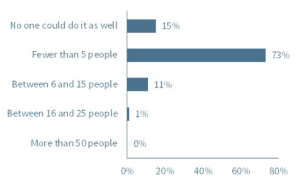

When asked to estimate how many executives are capable of stepping into the CEO role at their company and performing at least as well as their current CEO, directors estimate that fewer than four executives have the requisite skills (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

“Roughly how many people, including those both inside and outside your company, are capable of stepping into the CEO role at your company today and doing at least as well as your current CEO?

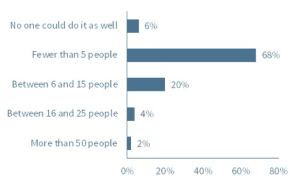

Their assessment of a small labor market is not confined to their own company and extends to other companies in their industry. When asked how many executives could step into the CEO role of their biggest competitor and perform at least as well as that company’s CEO, directors estimate that only six executives would be qualified (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

“How many people, including those both inside and outside their company, are capable of stepping into the CEO role at your biggest competitor and doing at least as well as their current CEO?”

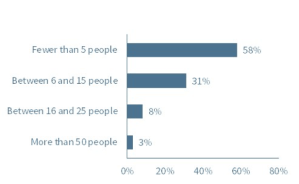

They also believe that only nine executives would have the skills needed to turn around a company struggling in their industry (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

“If a large company in your industry were in need of a turnaround, how many people have the skills required to succeed as its CEO?”

These are surprisingly low numbers, and have important implications for corporate governance:

- Efficiency of the labor market for CEO talent: Given the scarcity of outstanding CEO talent among large corporations, it is unlikely that the labor market for CEOs functions efficiently. That is, the matching process for linking qualified talent with suitable job opportunities likely does not occur as economically as it does for other job types. With an inefficient labor market, management might face less pressure to perform and distortions can arise in the balance of power between the CEO and the board, and in compensation.

- Compensation: A tight labor market for CEO talent might help to explain high compensation levels, particularly among the largest U.S. companies. If only a limited number of executives are qualified to run these companies—and if outstanding CEO talent is critical for their success—then it is reasonable to expect that boards will offer large sums of money to attract their top candidate or retain their current CEO. The cost of losing him or her to a competitor would be too high.

- Performance Evaluation: Directors’ view that capable CEO candidates are extremely scarce is likely to color their assessment of their CEO’s performance, as any evaluation that implies that the CEO should be replaced requires the board to take on the risk associated with finding a replacement. This risk aversion may encourage boards to tolerate both performance and behavior that would be not be acceptable if they perceived the existence of a large pool of highly qualified candidates.

- Succession planning: If directors believe that executives require special and rare attributes that are difficult to identify (including the right set of functional, industry, and managerial experience combined with leadership qualities and cultural fit), identifying these candidates prospectively becomes even more important and reinforces the need for rigorous succession planning.

- Talent development and retention: Internal executives continue to be the most promising source of candidates for most companies when it comes to future succession. Given the board’s familiarity with them, the visibility of their track record, and their tested cultural fit, it is more economic for most companies to invest in—and retain—their best internal talent.

ENDNOTE

- For complete survey results, see Stanford Graduate School of Business and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, “CEO Talent: America’s Scarcest Resource? 2017 CEO Talent Survey,” (2017), available at: https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/ceo-talent-americas-scarcest-resource-2017-ceo-talent-survey.

This post comes to us from Nicholas Donatiello, David Larcker and Brian Tayan. Donatiello is a lecturer in corporate governance at Stanford Graduate School of Business. Larcker is the James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting and Senior Faculty at the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University. Tayan is a researcher at the center. The post is based on their recent article, “CEO Talent: A Dime a Dozen, or Worth Its Weight in Gold?,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog