Insider trading and market manipulation — two of the most high-profile categories of financial misconduct — have resulted in several major cases, and significant sanctions in recent years. Our recent article examines the type, frequency, and severity of sanctions imposed for insider trading and trade-based financial market manipulation (“market manipulation”) over seven years from 2009 to 2015 in Australia, Ontario (Canada), Hong Kong, Singapore, and the United Kingdom (UK).

Regulatory Enforcement Approaches – Market Manipulation

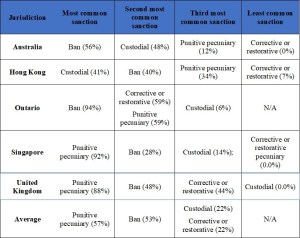

What we found from our empirical research was that even in jurisdictions with similar insider trading and market manipulation laws, enforcement approaches differed significantly. A summary of the sanctions imposed for market manipulation across the five jurisdictions is provided in the following table.[1] A summary of the results from our study of insider trading sanctions (which included the U.S.) is provided in our earlier blog post here.

Breakdown of Sanctions Imposed for Market Manipulation Across Jurisdictions

Below are our key findings on the enforcement approaches relating to market manipulation.

Australia

A typical offender in Australia received a ban or a custodial sentence. The number of bans is significant given that offenders convicted of market manipulation in the criminal courts are also subject to automatic disqualification from managing corporations in Australia for five years. Pecuniary sanctions were very rarely imposed on offenders.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, around 41 percent of offenders received a custodial sentence, and a slightly smaller proportion of offenders (40 percent) received a ban. Around a third of offenders also received a punitive pecuniary penalty. However, nearly two thirds of the custodial sentences were fully suspended, and the other sentences tended to be substantially shorter than in Australia. A typical offender in Hong Kong received a ban, a short custodial sentence, or a small pecuniary penalty.

Ontario

Ontario was characterized by a high proportion of offenders receiving bans, and a relatively high number of pecuniary sanctions. However, there was only one custodial sentence imposed for market manipulation in Ontario during the study period, so a typical offender received a ban and a pecuniary sanction.

Singapore

In Singapore, pecuniary sanctions were imposed on nearly all offenders. Bans were imposed on around 28 percent of offenders. In Singapore, a market manipulation conviction or a civil penalty also results in automatic management disqualification for five years.

UK

A typical offender in the UK received a punitive pecuniary sanction, and in some cases also a ban. There appear to have been no criminal sanctions imposed for market manipulation in the UK, despite the fact that insider trading offenders are increasingly prosecuted criminally in that jurisdiction.

Sanction Severity and Enforcement Intensity – Comparing Market Manipulation and Insider Trading Sanctions

We found differences in sanction severity and enforcement intensity in the five jurisdictions. Under our model, the level of enforcement intensity is influenced by both the level of enforcement activity and sanction severity.

One of the complexities in comparing the severity of sanctions and enforcement intensity across jurisdictions is the different enforcement approaches taken. That is, offenders:

- often receive different types of sanctions for the same conduct, and/or

- received more than one sanction for the same misconduct (for example, a financial penalty and a ban from managing companies).

To account for this, we developed a model that assigned numerical values to sanctions based on their type and magnitude. Broadly, the model ranks custodial sentences with a minimum period of incarceration as most severe, followed by (a) criminal sanctions that involve convictions but not incarceration; (b) banning orders; (c) sanctions that are purely monetary; and (d) standalone declarations of contravention and cease and desist orders. All of the sanction values for a given offender are added together— the higher the value of combined sanctions, the more severe the sanctions received by the offender.[2]

Sanction Severity

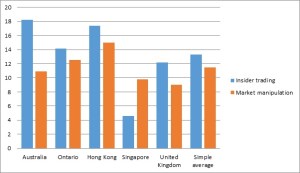

We used our model to compare the severity of sanctions imposed for market manipulation and insider trading in each jurisdiction. As shown below, sanctions imposed for insider trading were more severe than those imposed for market manipulation in each of the jurisdictions apart from Singapore.

Severity of sanctions (as estimated by median sanction values)

There were also considerable differences in sanction severity between jurisdictions. The differences were more significant for insider trading than for market manipulation. The countries with the most severe sanctions for market manipulation were Hong Kong (15.00) and Ontario (12.50), while the most severe sanctions for insider trading were imposed in Australia (18.2) and Hong Kong (17.35). The least severe sanctions for market manipulation were imposed in the UK (9.02), while in Singapore insider trading sanctions were even less severe (4.6).

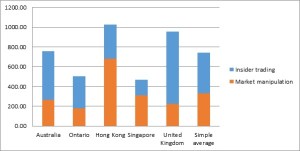

Enforcement Intensity

We also found that there are considerable differences in the levels of enforcement intensity relating to insider trading and market manipulation among the five jurisdictions, which may indicate differences in regulatory enforcement priorities. As illustrated below, the stronger enforcement focus in Hong Kong and Singapore appears to be on market manipulation, while in Australia, Ontario, and the UK it is on insider trading.

Enforcement intensity (as estimated by total sanction values)

Previous research in this area typically focused on legal analysis of legislation and judgments. But academic studies have shown that strong laws without strong enforcement are not enough to maintain trust and confidence in the integrity of financial markets.[3]

The increasing pressure on financial regulators to be transparent and accountable, and a trend towards increased empiricism in enforcement reporting, has been observed.[4] However, evaluating the effectiveness of regulatory action is challenging.[5] The frequency of successful prosecutions and severity of sanctions are two outputs that can be measured and analyzed. Our application of an empirical model to provide insights into the level of enforcement intensity provides an example of how to evaluate regulatory effectiveness.

By providing empirical evidence of the actual sanctions imposed for insider trading and market manipulation across a wide range of jurisdictions, our study aims to provide a more accurate picture of the enforcement landscape for insider trading and market manipulation. Our findings also have implications in terms of the ability of the various regulators to create a credible deterrent. These findings warrant further research on the enforcement priorities and practices of regulatory bodies and other enforcement agencies.

ENDNOTES

[1] The combined figures in the table above often exceed 100 percent as in many cases offenders received more than one type of sanction. For example, in Ontario, 94 percent of offenders received bans, 59 percent received a punitive pecuniary sanction, 59 percent received a corrective or restorative pecuniary sanction, and only 6 percent received a custodial sentence (so in most cases an offender received a ban, a punitive pecuniary sanction, and a corrective or restorative pecuniary sanction).

[2] For more detail on the empirical model, and on our findings in relation to insider trading, see L Bromberg, G Gilligan and I Ramsay, “The Extent and Intensity of Insider Trading Enforcement – an International Comparison” (2017) 17 Journal of Corporate Law Studies 73, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2919153.

[3] Bhattacharya and Daouk found that the cost of equity in a country does not change after the introduction of insider trading laws, but decreases significantly after the first prosecution: see U Bhattacharya and H Daouk, “The World Price of Insider Trading” (2002) 57 Journal of Finance 75, 77. See also M I Steinberg, “Insider Trading, Selective Disclosure and Prompt Disclosure – a Comparative Perspective” (2001) 22 University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Economic Law 635, 636.

[4] G Gilligan, J Hedges, P Ali, H L Bird, A Godwin and I Ramsay, “Regulating by Numbers: The Trend Towards Increasing Empiricism in Enforcement Reporting by Financial Regulators” (2015) Law and Financial Markets Review 260, 40, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2728071.

[5] See e.g. U Velikonja, “Reporting Agency Performance: Behind the SEC’s Enforcement Statistics” (2016) 101 Cornell Law Review 901.

This post comes to us from Lev Bromberg, George Gilligan, and Ian Ramsay. Bromberg is a research fellow, Gilligan is a senior research fellow and Ramsay is the Harold Ford Professor of Commercial Law and director of the Centre for Corporate Law and Securities Regulation at the University of Melbourne’s Melbourne Law School. The post is based on their recent article, “Financial Market Manipulation and Insider Trading: an International Study of Enforcement Approaches”, available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog