In an economic environment where technological disruption and regulatory upheaval are the norm, understanding innovation processes is essential to aggregate economic growth and individual companies’ survival. As a result, how innovations are produced in a wide range of markets has attracted a massive amount of scholarly and popular attention.[1] Yet, few have focused upon how the legal infrastructure, to use Gillian Hadfield’s term, underlying those innovations develops over time to meet new market needs. We know more about how our iPhones were developed than how market institutions evolved to make the iPhone possible.

In a new paper, The Architecture of Contract Innovation, I take a step toward addressing that gap in our understanding. My focus is upon the legal lifeblood of our economic system: contracts.

Innovation problems are arguably the most pressing, if unaddressed, issue in modern contract law. On one hand, the use of standardized provisions—or boilerplate—often hinders innovation as parties are reluctant to deviate from established terms considered to be “market.” Scott & Gulati’s detailed account of path dependency in sovereign debt indentures provides a bracing example of a market getting stuck in such a rut. At the same time, new technologies, such as blockchain contracting and advances in machine learning, are disrupting traditional modes of providing transactional services. In some markets, contractual innovation has slowed to a trickle, while in others the floodgates are opening.

This paper uses the M&A market as a lens for studying contractual innovation. Regular, if often incremental, innovation occurs in M&A, with examples including the development of the poison pill, no-shop/go-shop provisions, top-up options, forum selection bylaws, etc. M&A is particularly useful for studying innovation because it presents a puzzle: M&A agreements are highly complex and yet exhibit limited amounts of standardization. In a phrase, M&A agreements are “mass customized”—they are produced at scale while incorporating material amounts of deal-specific tailoring. That is puzzling because the returns to standardization would appear to be high, given how complicated M&A contracts are. So, something else must be at work. How do M&A lawyers do it?

The paper explores two possibilities. The first is that deal lawyers use modular design to make it easier to customize complicated M&A agreements. A modular system is one where sub-systems are separated from one another, and interactions between the sub-systems are managed through a single interface.[2] Modularity reduces innovation costs by allowing one to change a module, or even remove or add an entire module, without affecting other parts of the system. The USB port on your laptop is a good example—you can plug many types of peripherals into that port, and they are immediately interoperable with other parts of your computer without overhauling your entire system’s architecture.

The second possibility is that deal lawyers use “flexible specialization” to reduce the costs of making adjustments to complex agreements whose sub-systems are not modularized but are rather kept highly integrated.[3] The idea here is that the costs of innovation are reduced by maintaining effective information flows and learning routines among the designers of the system. Rich information and efficient routines allow designers to quickly process changes throughout the entire system. While modularity is a structural fix to the innovation problem, flexible specialization is a social fix. The uniquely collaborative production system Toyota Motor Company developed with its suppliers in the second half of the 20th century and the highly cooperative supplier networks of northern Italy are two examples of flexible specialization.

To analyze whether modularity or flexible specialization strategies are used, the paper employs methods for studying complex technological and social systems, which have been developed in systems engineering, business strategy, and sociology. In short, it treats an M&A agreement like any other piece of complex technology—such as a semiconductor, a software program, or an automobile—and studies its internal structure. The “engineering” in Gilson’s classic “transaction cost engineering” concept is taken literally, and no longer metaphorically.[4]

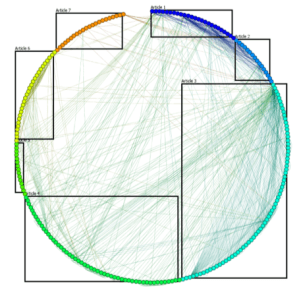

In a nutshell, the analysis works as follows. Using a sample of publicly available contracts, the components of an agreement are identified and explicit interactions between them are plotted on a “design structure matrix.” That matrix serves as the basis for constructing a network graph of the interactions between the agreements’ provisions. The figure below is an example: It shows interconnections between provisions in the merger agreement designed for the 2012 NYSE/Euronext deal. Once the contract is rendered as a network graph, we can then use some math to measure the extent to which the contractual system has discrete modules.

NYSE/Euronext Agreement, Dec. 20, 2012

Network of Direct References between Provisions

(Main Articles of the Contract Indicated by Bounding Boxes)

The results of the analysis find limited evidence of modularity in the M&A agreements sampled. Rather than modular systems, M&A agreements appear to be more integrated, as the web of interactions among provisions in the figure above suggests. Interestingly, an analysis of the ABA’s model merger agreement was also undertaken, resulting in higher modularity scores than those for the sampled contracts. That may suggest that modular design plays a more important role in the early stages of designing an M&A agreement, with the contractual system becoming more integrated in the later stages as the contract is fine-tuned.

The paper also analyzes the structure of the teams of attorneys designing the agreements. Work by Lyra Colfer and Carliss Baldwin identifies empirical support in a variety of industries for what they call the “Mirroring Hypothesis,” which claims that product architecture and organizational architecture mirror one another. For instance, a modular product should have a modular team of designers. Therefore, this study asks whether the internal structure of the M&A deal teams at the law firms designing the sampled agreements are more modular or integrated. Deal teams at three New York law firms—Cravath, Davis Polk, and Shearman & Sterling—were analyzed.[5] Data on the deal teams for the sampled transactions were hand-collected from publicly available press releases routinely issued by the firms. The results of the organizational analysis do indeed mirror the analysis of agreement structure: Over time, the network of attorneys working on M&A deals at the three firms appears less modular and more integrated, just like the contracts. Although the time period sampled was only a few years, the deal teams appeared to recombine quite differently at the firms from deal to deal, resulting in a network where information flows were robust and dynamic. The organizational magic was not in any single lawyer or small clique but rather the broader network of expertise in which all team members partook.

What does this mean for our understanding of contract innovation? The first take-away is that a modular design is not required for successful innovation in complex commercial agreements. Modular design may work well in some areas—the modular structure of ISDA’s swaps & derivatives documentation is a good example—but it is not necessarily the only game in town. The second take-away is that, where agreements have an integrated architecture, a key necessary condition for vibrant contractual innovation is a dynamic network of experts. To adapt a somewhat tired adage from childrearing: In M&A, “it takes a village.”

There is much more work to be done to further explore innovation in the M&A market and to test those preliminary results. Some of that is already underway, such as my related paper with Cathy Hwang, which opens a window on how this research matters for classic issues of contract interpretation. Advances in natural language processing are also making much more detailed analyses of complex agreements possible. The near-future promises a number of interesting developments, as research continues, driven by the need to better understand the pace and trajectory of change in our markets.

ENDNOTES

[1] Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail (1997) is a well-known example.

[2] Carliss Baldwin & Kim Clark’s Design Rules (2000) provides a comprehensive treatment of modular design in the strategic context.

[3] The term “flexible specialization” comes from Michael Piore & Chuck Sabel’s landmark work, The Second Industrial Divide: Possibilities for Prosperity, which articulates an alternative to the mass production paradigm widely-accepted in the United States.

[4] Ronald Gilson, Value Creation by Business Lawyers: Legal Skills and Asset Pricing, Yale Law Journal (1984).

[5] All three firms have New York origins but now serve multinational client bases.

This post comes to us from Matthew Jennejohn, the Robert W. Barker Professor at BYU Law School. It is based on his recent paper, “The Architecture of Contract Innovation,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog