Over the years, a consensus on the best corporate governance practices has emerged. The OECD Guidelines of Corporate Governance epitomize a canon of such practices, including things like having non-executive shareholders on boards, having an audit committee, and following special rules when trading with other companies owned by your company’s bosses. Yet, every canon brings about its own counter-reformation. Over the years, there have been calls to treat emerging markets like Russia and China as special cases. State-owned capital, combined with Asian values, has obviously paid off – as evinced by China’s more than 5 percent growth. Is it true, though, that China is a special case?

Our recent work suggests the canon applies every bit as much to China as to other jurisdictions. The corporate governance canon has led to increases of about 7 percent, on average, in the share price of Chinese companies and greater total profit of about $330 billion.

Our study looked at the expected increase in Mainland Chinese companies’ share prices in Hong Kong, using their peers listed on the Mainland as a benchmark. We looked at the rise of all Chinese companies’ share prices from 2011 to 2013 and separated the results according to whether the company was listed in Hong Kong or on the Mainland. We gauged the effect of the corporate governance canon by capturing the difference in corporate governance rules between China and Hong Kong. We also tried to capture the way those prices changed after the Hong Kong Stock Exchange’s Listing Rules implemented more of the canon’s principles. Economists call such a procedure a difference-in-differences methodology, the first difference being between China and Hong Kong, and the second being between the periods before and after corporate governance reform in Hong Kong. We didn’t use a lot of fancy regression analysis but confirmed many previous studies while getting a ball-park figure for the value of corporate governance.

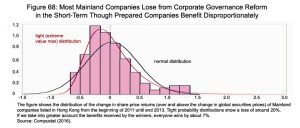

Yet, every canon has its downsides. The figure below shows the distribution of share price changes for each Hong Kong-listed company. While the average share price increased 7 percent, many companies lost value (as shown by the left side tail of this distribution). Moreover, when we fiddled with the way we thought these share prices should be distributed, most of these gains vanished. We show this by comparing the usual bell-shaped distribution in black with a more skewed one shown in red.

The conclusion remains nonetheless: Applying the corporate governance canon in China probably helps more than it hurts, especially in recent years.

This post comes to us from professors Say Hak Goo and Bryane Michael at the University of Hong Kong. It is based on their recent paper, “The Value of the Corporate Governance Canon on Chinese Companies,’ available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog