While the behavior of mutual fund investors is an active field of study within finance, we do not know very much about how these behaviors have changed over time. The simple reason for this is that most studies in this area examine only a single, static sample period or conduct only a very limited analysis of changes in behavior over sample sub-periods. Yet a great deal has changed since the early 1990s, when most of the accurate and detailed mutual fund data became available. Financial markets, technology, and resources for investor education all look very different in 2018 than they did in 1992. In addition, the Great Recession of 2007-09 was the longest and deepest recession in the post-War era and was more deeply felt by many Americans than previous recessions. Thus, it is interesting to ask whether and how investor behavior changed during this period of economic turmoil, and whether such changes have persisted into the most recent period of growth and recovery.

In our study “The Economic Determinants of Mutual Fund Investor Behavior,” we conduct a detailed examination of the factors that determine investor cashflows into equity mutual funds and how those determinants have changed over the past 25 years (1992-2016). We find:

- Investor flows have become more sensitive to expenses and past fund risk and less sensitive to past returns and pay attention to past alpha over much of the sample period. Past academic studies have documented that higher expenses are associated with lower fund returns, while higher alphas (by definition) are measures of higher risk-adjusted returns. Thus, investors are paying more attention to fund characteristics that should be beneficial (e.g. risk, alpha, and expenses),

- Investor cashflows have become less highly correlated with past returns, and in fact the correlation between past returns and investor cashflows has essentially disappeared since the Great Recession. Thus, investors are paying less attention to characteristics that don’t benefit them (e.g. they are doing much less return-chasing than in the past).

- Investor cashflows are positively correlated with past alphas – that is, investors chase past alphas, and this behavior doesn’t change much in our sample period. We estimate the economic impact of this behavior and find that investors earn lower returns than they would if they did not chase alpha. In fact, we find that chasing past alphas is the most detrimental of all investor behaviors.

We find the last two points interesting. The mutual fund data suggest that even prior to the Great Recession, investor return-chasing temporarily disappeared (or at least diminished) during market downturns. But in the past, return-chasing always reappeared during the subsequent market recovery. What is different about the most recent period is that return-chasing has not reappeared during the market recovery since the Great Recession. And while our sample data don’t allow us to say anything formal about causation, it is interesting to conjecture about the reasons for the observed changes in mutual fund investor behavior.

C.S. Lewis is said to have noted that “Hardships often prepare ordinary people for an extraordinary destiny,” and while the end of return-chasing could hardly be described as an extraordinary destiny, there is a seed of truth in the idea that only by experiencing a hardship can people get to where they need to be. Developmental psychologists recognized long ago that stress and hardship are often the necessary precursors to moving to the next level of development. It is possible that periods of hardship (such as the Great Recession) may be precisely when investors are open to and able to receive information that allows them to truly learn at a level that translates into changed behavior. (It is also possible that investors have not learned anything and that return-chasing will reappear in the future; our data is limited in what it can tell us).

Changes in investor behavior are consistent with investor learning, which we hypothesized would lead to better outcomes. But (perhaps counterintuitively) we find that this is not the case. To measure the impact of investor behaviors on investor returns we use the Performance Gap (see Friesen and Sapp, 2007; Dichev 2007), which compares investors’ dollar-weighted returns to the underlying time-weighted returns of the fund. As explained by Friesen and Sapp (2007), this methodology “captures the interaction between all cash flows and returns to a fund over the entire sample period, thus measuring the full impact of investor cash flow timing decisions.”

We find that the average investor dollar-weighted return is about 1.2 percent below the average buy-and-hold return in investors’ underlying mutual fund nearly every year in our sample. This suggests consistently poor timing ability over the entire period that does not improve with the observed changes in investor behavior.

We then deconstruct the Performance Gap into the pieces attributable to each of the investor behaviors studied above (e.g. return-chasing, alpha-chasing, expense awareness, etc.). (As suggested by Hayley (2014), the Performance Gap actually has several components, only one of which is due to investor timing, so we deconstruct the Performance Gap into three components: one related to the sample distribution of returns, one related to fund selection, and the thir attributable to investor timing).

One interesting finding is that paying attention to alpha actually hurts investors more than chasing returns. At first, this result puzzled us in light of the fact that investors are now paying much more attention to fund alphas and almost no attention to fund returns. Alpha is an accurate measure of a mutual fund’s risk adjusted return, and paying attention to this measure should benefit investors. In addition, the mutual fund literature has documented a positive correlation between past and future alphas.

Here we come to a bridge that must be very carefully crossed. The mutual fund literature has established that in the pooled cross-section of mutual fund data there is a positive correlation between past alphas and future alphas ( if you regress future alpha on past alpha, the coefficient on past alpha is positive and statistically significant). However, this result actually captures or combines two distinct effects into one measure. The first effect is that some funds have higher average alphas than other funds. If you invest in a high-alpha fund, this is a good thing (what we call “good fund selection”).

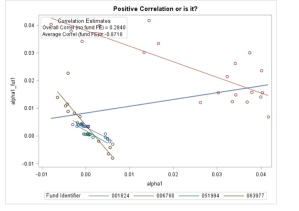

However, the second effect is that for an average individual fund, alphas are negatively autocorrelated. That is, if the fund realized a particularly high alpha last year, it will tend to realize a lower alpha next year, and vice versa. Investing in an individual fund after a period with a particularly high realized alpha is not a good thing (what we call “poor alpha timing”). The accompanying figure, which shows data on past and future alpha for four individual mutual funds, fits a regression line for each fund, as well as for the overall data. The pooled regression line has a positive slope, indicating a positive correlation between past and future alphas; each individual fund has a strongly negative slope, which captures the negative correlation.

It turns out that “poor alpha timing” dominates the “good fund selection,” and thus our result that alpha-chasing hurts investors actually makes sense when one recognizes that investor cashflows are highly correlated with past alphas, and that past alphas are negatively correlated with future alphas at the individual fund level.

In summary, our findings are consistent with a story in which investors are aware of the need to learn, and their behavior is consistent with their learning. Nevertheless, what they need to learn is complex and nuanced, and their learning imperfect. In addition, they are trying to learn about a constantly changing environment, and are subject to interruptions and dislocations such as the Great Recession. Their behavior suggests that they know alpha is important but have not yet figured out how to effectively differentiate past alphas from future alphas.

This post comes to us from Geoffrey C. Friesen, a professor at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, and Viet Nguyen, a PhD candidate at the university. It is based on their recent paper, “The Economic Impact of Mutual Fund Investor Behaviors,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog