Robust capital markets are widely believed to signal economic vitality, and a reliable barometer of such vitality was historically a rising number of IPOs and listings. Yet, as we are experiencing record setting economic expansion, that barometer has failed us. There has been a 20-year slide in the number of listed companies and the tepid-to-non-existent growth in IPOs. The number of listed companies peaked in 1997; listings today are below their level in the early 1970s. And the annual number of IPOs has never returned to their level in the 1990s. These developments have caused conservative politicians predictably to blame the heavy hand of regulation, seeing the decline in listings and IPOs as the canary in the coal mine signaling that regulation has gone too far. President Trump has recently joined this chorus. Below I point to far more likely explanations for these changes Not only do the facts raised below weaken substantially the basis for any deregulatory efforts, but they also raise very different public policy considerations of a type posing far graver consequences that should not be ignored. Simply stated, the current discussion focuses on the wrong cause for the canary’s death.

The president’s recent letter asking the SEC to study mandating only semi-annual and annual reporting by public companies is premised on the belief that mandatory disclosure raises the cost of being a public firm so that fewer rational captains of industry wish their companies to be public. It was just such outcries that drove the Congress, with White House support, to enact the JOBS Act in spring 2012, which ushered in a series of regulatory dispensations for “emerging growth companies” (a new expression coined in the act) as well as reducing the scope of the mandatory reporting requirements, introducing the crowdfunding exemption, and greatly expanding the scope of abbreviated public offerings via Regulation A. The JOBS Act and the recent requests by the president both rested on the same dubious empirical basis: declines in IPOs and listings.

A recent study by Credit Suisse, Incredible Shrinking Universe of Stocks (2017), points toward a more likely cause for the disappearance of public companies and IPOs in America. It is a cause that should elicit more profound public policy concerns than the disappearance of listings or fewer IPOs in which retail investors might stand a chance to participate. As the table below reports, during the 40 years in which listed companies declined 23.5 percent, the average market capitalization of a listed company increased 1,012 percent (and scaled to GDP the change was 190 percent.

Average Size of Listed Company

1976 1996 2016

Number of listed companies 4,796 7,322 3,671

Average market cap. $620 $1,683 $6,893

Market Cap. % of GDP 47.0% 104.7% 136.3%

Average age (years) of a listed company 10.9 12.2 18.4

$= (billions 2016 USD)

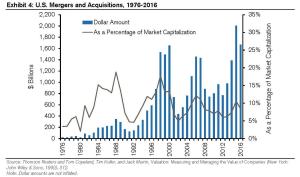

What we can see from the above data is we have incredible growth in industry concentration taking place within American product markets. This is further borne out by reports of merger activity, with company acquisitions starting to spike in the mid-1990s (when the number of listed companies was at its zenith) and remaining historically high ever since.

As we see from the above, merger activity became truly a growth industry at the same time that listings went into decline. This also is supported by the dramatic changes in market capitalization and years of existence of listed companies. The bottom line is that American listed companies are fewer in number, have existed longer, and are substantially bigger than in any time in history. The liquidity event for investors in successful startups is more frequently not an IPO but an acquisition by a well-established public company. The obvious issue we should focus on is whether this leads to harmful industry concentration (an antitrust consumer protection issue and not a “who can’t raise capital” concern).

Moreover, the over-regulation lament ignores the dramatic transformation of capital markets so that capital in large amounts is more cheaply and quickly aggregated via private markets than public markets. Consider the following. In 2016, there were only 26 U.S. technology IPOs that raised a total of $4.3 billion. In that same year, late-stage private (non-public) U.S. technology companies tapped the private funding market 809 times, raising a total of $19 billion. Maureen Farrell, Investors’ Lament: Fewer Public Listings, Wall St. J. at A-1, Jan. 5, 2017. This reflects that American capital markets are multi-dimensional, so that issuers and investors enjoy great freedom to match their unique endowments in the capital formation process. See generally Thompson & Langevoort, Redrawing the Public-Private Boundaries in Entrepreneurial Capital Raising, 98 Cornell L. Rev. 1573 (2013). This growing multi-dimensional setting is another explanation for the observed declines in IPOs and listings.

We also should observe that declines in listing and capital markets are not isolated to the United States. See Craig Doidge, G. Andrew Karolyi, Rene Stulz., The U.S. Listing Gap, 123 J. Fin. Econ. 464 (2017). While the decline in listing is relatively larger in the U.S., significant declines took place worldwide – where countries by and large mandate only semi-annual and annual reporting. This further points to the causes of the decline not being quarterly reporting.

The problem cannot therefore be that worthy enterprises are unable to raise capital at efficient rates; the evidence of today’s robust activity suggests the opposite. Indeed, there is no credible evidence that worthy enterprises lack capital. See James D. Cox, Who Can’t Raise Capital?: The Scylla & Charybdis of Capital Formation, 102 Ky. L. Rev. 849 (2014). This is why the justification for deregulating periodic reporting has more recently shifted to an equally unfounded complaint that declines in IPOs and listings are bad for retail investors because the “little guy” misses out on her chance to buy the next Apple (“some kind of fruit company” per Forest Gump). This reflects that robust capital markets delay the future Apples going public, so that a larger portion of their value is garnered by their pre-public institutional investors. The most fundamental rejoinder to this charge is it ignores that returns are all risk adjusted. Investors purchasing emerging companies earlier face greater risks. Do we truly believe Apple, Microsoft, or Facebook IPOs pass the suitability test imposed on brokers for customers who lack a sufficiently diversified portfolio?

Thus, any consideration of the president’s proposal to dramatically change the periodic reporting system requires a much more holistic inquiry, an inquiry well beyond the expertise of the SEC. Just as the architecture of the periodic reporting system was the product of the legislative process whereby wide viewpoints could be expressed, any thoughtful consideration of the president’s proposal should include inputs from multiple perspectives. This is bigger than just the retail customer.

This post comes to us from James D. Cox, the Brainerd Currie Professor of Law at Duke University.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog