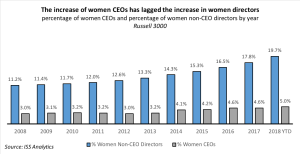

In the past year, the departures of several female CEOs have made headlines, raising concerns about a potential reversal in the growing trend of women in executive leadership roles. Meg Whitman (Hewlett-Packard Enterprise Co.), Indra Nooyi (PepsiCo Inc.), and Irene Rosenfeld (Mondelez International Inc.) are a few prominent examples that come to mind. While the data does not suggest a reversal to fewer women in top executive roles, we observe slower growth in the number of female CEOs as compared to the number of women directors, raising questions about gender biases in executive leadership beyond the glass ceiling.

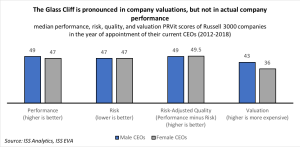

In this article, we explore the concept of the invisible precipice of a “glass cliff,” the hypothesis that women are more likely to be appointed to the top job at companies facing a crisis. We review company performance during the year of CEO appointment, and we find that women are more likely to be appointed as CEOs at companies with lower valuations compared to their peers.

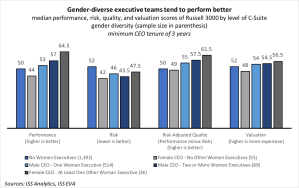

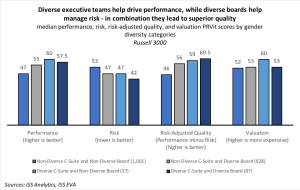

Furthermore, we examine the performance of companies where CEOs have held their roles for at least three years, and we observe that gender-diverse executive teams exhibit superior performance whether the CEO is female or male. Conversely, companies with no women in their top five executive roles or companies where the CEO is the only woman in the C-suite show the worst levels of performance, risk, and valuation. Companies that combined gender diversity in both the C-Suite and the board showed overall the best results in terms of risk-adjusted quality of performance, as we detect C-Suite diversity driving strong performance, while board diversity may help companies better manage risk.

Evaluating Company Performance

In our review of company performance, we use the ISS EVA proprietary scoring methodology PRVit (Performance, Risk, and Valuation information technology). The scores represent a percentile rank of companies on a scale of 0 to 100 compared to their respective industry for each of the categories of evaluation. The Performance score assesses companies’ ability to earn and increase profitability based on the Economic Value Added framework, with a higher score indicating better performance. The Risk score measures a company’s volatility in terms of stock price and profitability, as well as vulnerability in terms of the company’s ability to meet debt obligations. In this case, a lower Risk score is considered a better indicator of risk management. A combination of the Performance and Risk scores results in the Risk-Adjusted Quality score, where a higher score represents better overall performance quality. Finally, the Valuation score ranks companies based on their current market valuations using a variety of measures including market-to-book ratios and profitability multiples.

Examining the Glass Cliff Hypothesis

While there has been a steady increase of female CEOs in the Russell 3000 over the past decade, currently only about 5 percent of Russell 3000 companies have a female CEO. The percentage of female CEOs does not vary by company size, as we observe the same general trends in the gender of executive leadership for both small and large firms.

For the small percentage of women that make it to the top, the “glass cliff” suggests additional challenges. Coined in a 2005 academic study by Michelle Ryan and Alexander Haslam of Exeter University, the term “glass cliff” refers to the phenomenon of women being appointed to leadership roles at companies experiencing bad performance. The theory that women may be appointed to CEO roles that are less desirable has significant implications for the evaluation of female executives and succession planning, as the results may reveal biases in both the recruitment process and post appointment.

To test for the existence of a glass cliff, we reviewed performance, risk, and valuation scores of Russell 3000 companies during the year of appointment of their current CEOs. Specifically, we reviewed CEO appointments that took place from 2012 to 2018. In our analysis, we do not observe a significant difference in company performance based on the gender of the newly appointed CEO. However, we do note a considerable difference in market expectations in the form of lower valuations for the 84 companies that have women CEOs compared to the 1380 companies that appointed a male CEO. The scores suggest the potential existence of the glass cliff in terms of perceptions about the company as reflected in lower stock prices.

Gender-Diverse Executive Teams Exhibit Superior Performance

Beyond the initial hurdles of the glass ceiling and the glass cliff, women CEOs generally show performance results similar to or superior to their male counterparts. As CEOs do not operate in a vacuum, the composition of the entire C-Suite and the board also warrant a closer look in this context. We examined companies where CEOs had a tenure of at least three years in their position, and found a correlation between C-Suite gender diversity and performance. Companies with women CEOs and at least one more woman in the top five executive positions exhibit the best performance than any other group of companies in terms of C-Suite gender diversity. This trend is also true for companies with male CEOs and diverse executive teams. Companies that have no female executives or where the CEO was the only woman in the C-Suite had the worst median levels of performance and valuation. All diversity is not created equal, as we see performance improving as gender diversity increases. Hence, gender diversity in the executive team appears as the key differentiating factor when it comes to company performance. Using a median test analysis for the median scores of the five groups, we receive P values of 0.106 for the Performance score, 0.042 for the Risk score and 0.018 for the Risk-Adjusted Quality score, indicating a statistical significance in a difference in the medians for each score.

Combining C-Suite Diversity with Boardroom Diversity

We further reviewed how diversity in the C-Suite may interact with diversity in the boardroom by categorizing companies in terms of diverse executive teams and diverse boards. We considered diverse executive teams as those with at least two women in the C-Suite, while diverse boards were defined as boards with at least two women non-CEO directors.

We found that companies that lack diversity in the boardroom and in the C-Suite had the worst results in terms of performance, risk, and valuation, while companies with diverse executive teams exhibited the best results even when their boards were non-diverse. However, board diversity appears to consistently correlate with a lower risk profile. Overall, companies that combine diversity in the C-suite with diversity in the boardroom have the highest scores in terms of risk-adjusted quality. These results suggest that diverse executive teams may be better able to drive superior performance results, while diverse boards help companies improve their risk management. Given the executive responsibilities of management and supervisory responsibilities of the board, these results make intuitive sense. A median test analysis confirms the statistical significance of the results, as the P values are less than 0.005 for the Performance, Risk and Risk-Adjusted Quality scores. However, further studies may be required to establish a potential causal relationship.

Breaking Barriers to Gender Diversity

A previous ISS publication (Women in the C-Suite: The Next Frontier in Gender Diversity) identified five emerging best practices for promoting gender diversity in leadership roles, including:

- addressing subtle bias,

- establishing clear diversity targets,

- redefining the path to executive leadership,

- establishing mentorship and sponsorship programs for women, and

- providing support towards work-life balance.

The results of our research on C-Suite gender diversity and performance suggest that investing in these best practices can pay significant dividends for organizations. Below we draw some key takeaways specifically in relation to considerations for companies in the C-suite hiring decision-making process.

- Team Gender Diversity Has Stronger Impact than CEO Gender: CEOs, regardless of their gender, do not operate in a vacuum. Our analysis suggests that the overall gender diversity in the C-Suite has significant impact on performance, risk, and valuation. Our results show that companies where the CEO was the sole female in the C-Suite performed worse than their peers. Focusing on gender balance in the C-suite and senior management has more significant impact on performance than the appointment of a female CEO, even though the latter is more likely to make headlines. As part of the review of gender balance in the C-Suite, a focus on positions that lead to the top job will further contribute towards overcoming invisible hurdles and biases in the CEO hiring process.

- Examine Biases and Be Willing to Put Women in Charge: Research into what causes the glass cliff (HBR: How Women End Up on the “Glass Cliff”) points to a status quo bias. Specifically, when companies perform well, the study found “people prefer leaders with stereotypically male skills, but when a company is in crisis, they think stereotypically female skills are needed to turn things around.” With the overwhelming majority of companies currently having a male CEO, male CEOs are more likely to remain in or get promoted to similar positions when a company does well. However, the study also found that those effects become less pronounced “as people become more used to seeing women at the highest levels of management.” The importance of seeing more women leading companies seems to have the potential for significant knock-on effects for addressing the glass cliff as well the glass ceiling overall (WEF: The key to closing the gender gap? Putting more women in charge).

- Review the Short List Process: Research highlights that companies may use different selection criteria when appointing a female CEO compared to a male CEO. According to a McKinsey study (Unlocking the Full Potential of Women in the U.S. Economy), men tend to be evaluated based on their potential, while women based on past performance. While our analysis does not explore the potential differences in leadership styles or qualities of female CEOs and top executives, the overall numbers suggest that gender-diverse executive teams outperform their all-male counterparts. Therefore, companies stand to benefit by re-examining their short list practices, including the interview process itself.

This post comes to us from Institutional Shareholder Services. It is based on the firm’s recent publication, “Female CEOs on a Glass Cliff? A Look at Gender Diversity and Company Performance,” dated October 26, 2018, and available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog