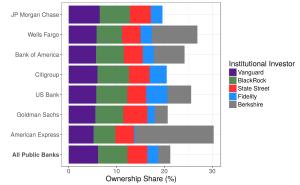

In recent years, large asset managers and other institutional investors have come to own increasingly large shares of firms that are competitors. For instance, BlackRock owns shares of both Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase. Such common ownership is prevalent in many industries. For example, the graph below illustrates the prevalence of common ownership in the U.S. banking industry. It shows the ownership stakes by the five largest bank shareholders in seven of the largest U.S. banks, and in all public banks combined:

Figure 1 Ownership stakes by the five largest bank shareholders in seven of the largest U.S. banks, and their ownership in all public banks combined.

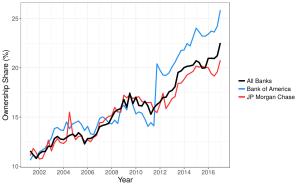

It is also worth noting that common ownership has grown in recent years. The graph below shows the growth of bank ownership by the same five shareholders over time. Over the past 15 years their ownership in publicly-listed banks almost doubled. This growth was driven in part by the growing popularity of index funds.

There is ongoing debate about whether such common ownership reduces competition among firms. For instance, wouldn’t BlackRock and Vanguard prefer reduced competition between Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase? This debate was sparked by two papers by Azar, Schmalz, and Tecu (2018) on the airline industry and Azar, Raina, and Schmalz (2016) on the banking industry, which found that common ownership is associated with less competitive pricing. Some subsequent papers found no robust anticompetitive effects in preliminary estimates (e.g. Gramlich and Grundl (2017), Kennedy et al (2017)).

The Effect of Common Ownership on Profits

These studies have largely focused on the effect of common ownership on prices, and to a lesser extent on quantities. In our most recent paper, “The Effect of Common Ownership on Profits: Evidence From the U.S. Banking Industry,” we argue that looking at profits is a more direct test of the underlying theory.

The underlying theory (O’Brien and Salop (2000)) predicts that common ownership can be anticompetitive because it changes the objective function of firms, such that they no longer seek to simply maximize their own profits. Instead, they now also place some weight in their objective function on the profits of rival firms that are held by a common shareholder. In our paper we test this theory by examining whether shifts in profit weights that are predicted by the theory are indeed associated with shifts in actual profits. For example, if a firm places less weight on its own profits and more on the profits of rivals, the rival profits should increase, everything else equal.

The U.S. banking industry is a good testing ground for this theory, because there is considerable variation in the profit weights that are predicted by the theory, both across banks and over time. There are more than 400 publicly-listed banks in the U.S. and more than 5,000 private banks. The O’Brien and Salop model predicts that most publicly-listed banks should care less about maximizing their profits today than they did 20 years ago when common ownership was less prevalent. On the other hand, privately held banks have had very little common ownership throughout the 20 year period, and should therefore benefit from the less aggressive competition by their increasingly commonly-owned public rivals.[1]

Our paper uses accounting data from the banking industry to examine empirically whether shifts in the profit weights are associated with shifts in profits. We present the distribution of a wide range of estimates that vary the specification, sample restrictions, and assumptions used to calculate the profit weights. The distribution of estimates is roughly centered around zero, though we find statistically significant estimates in either direction in some cases. Economically, most estimates are fairly small. Our interpretation of these findings is that there is little evidence for economically important effects of common ownership on profits in the banking industry.

Are All Shareholders the Same?

The existing literature on common ownership to this point has treated all shareholders the same. For example, common ownership through an index fund is treated the same as common ownership through an activist investor or a hedge fund. However, these different shareholders have different incentives and different means by which they can influence the management of firms, so we believe this assumption should be investigated empirically.

For example, “direct shareholders”—such as Berkshire Hathaway—are the ultimate owners of shares. This is in contrast to asset managers, such as Vanguard or Fidelity, that manage shares owned by their clients. Direct shareholders may benefit more from increasing share prices (as a consequence of decreased competition) than asset managers that typically earn a small, fixed fee as a percentage of assets under management.

Similarly, “active investors” are investors that try to pick winning stocks, as opposed to “passive investors” that simply replicate an index. Passive investors hold the same portfolio of stocks as their competing index funds (and largely compete on fee minimization), so they may stand to gain less from competition reduction among portfolio firms which equally benefits asset managers against whom they compete. Active asset managers, however, hold a unique portfolio, and are perhaps more likely to outperform their rivals if their portfolio firms were to soften competition.

We obtain some preliminary estimates that rely on common ownership only through either direct shareholders or active investors and find no robust evidence that common ownership affects profits.

Outlook

Today, the conclusions in the empirical literature regarding the competitive effects of common ownership are conflicting. While some studies find large anticompetitive effects, others find no robust evidence for such effects. The empirical literature is still in its infancy and growing quickly. While the empirical evidence is accumulating, the concern about competitive effects of common ownership will continue to become a more and more pressing issue, as the shift from active asset managers to index investing leads to more common ownership.

ENDNOTE

[1] The substantial variation in common ownership within the group of publicly-listed banks also allows for testing of the theory without comparing listed and unlisted banks.

REFERENCES

Azar, José, Martin Schmalz, and Isabel Tecu, “Anticompetitive Effects of Common Ownership,” Journal of Finance, 73(4), 2018, pp. 1513-1565.

Azar, José, Sahil Raina, and Martin Schmalz, “Ultimate Ownership and Bank Competition,” [2016 NBER SI IO].

Gramlich, Jacob, and Serafin Grundl (2018). “The Effect of Common Ownership on Profits: Evidence From the U.S. Banking Industry,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2018-069. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Gramlich, Jacob, and Serafin Grundl (2017). “Estimating the Competitive Effects of Common Ownership,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2017-029r. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Kennedy, P., D. P. O’Brien, M. Song, and K. Waehrer (2017): “The Competitive Effects of Common Ownership: Economic Foundations and Empirical Evidence.”

O’Brien, D. P., and S. C. Salop (2000): “Competitive effects of partial ownership: Financial interest and corporate control,” Antitrust Law Journal, 67(3), 559–614.

This post comes to us from Serafin Grundl, a senior economist for the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and from Jacob Gramlich, chief of the financial structure section at the board. It is based on their recent paper, “The Effect of Common Ownership on Profits: Evidence from the U.S. Banking Industry,” available here. The analysis and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by other members of the staff, by the Board of Governors, or by the Federal Reserve Banks.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog