Just as the Mamas & the Papas pioneered the folk-rock scene of the 1960s as one of the first truly gender diverse music group, their native state of California is breaking ground for increased board gender diversity in the United States. Unlike a growing number of countries in Europe and around the globe that have instituted comply-or-explain policies and/or gender diversity quotas, the U.S. has not implemented regulatory requirements in relation to board gender diversity. The record-breaking influx of female board members observed in the past two years is primarily driven by private ordering through company-shareholder engagement, shareholder proposals, and an increasing number of large asset managers adopting voting policies emphasizing board gender diversity. The U.S.’s market-driven approach to gender diversity may begin to change, as quotas mandating board gender diversity are introduced and put into law in the state where the highest number of U.S. companies maintain their headquarters. California’s recently passed Senate Bill (SB) 826 is the first law in the United States to introduce such measures.

Our research finds that 89 percent of California-based companies will need to make changes to their board composition in the next three years to meet the new law’s requirements. California-based companies appear to lag behind other states in board gender diversity, as a relatively small percentage of them have at least two women on their board. Our projections indicate that SB 826, once implemented, could have significant reverberations for the entire U.S. market, potentially increasing the number of women on U.S. boards by 22 percent. Even if SB 826 faces significant legal challenges, our assessment is that the new legislation will have a long-lasting effect on board gender diversity in the Golden State and beyond.

The New SB 826 Mandate

The Bill first passed 41 to 26 in the State Assembly on August 29, 2018, before also passing in the California State Senate with a vote of 23 to 9 the following day. One month later, on September 30, 2018, California Governor Jerry Brown officially signed SB 826 into law. This new law will require companies’ boards to have at least one woman by the end of 2019, and will apply to companies defined as “domestic general corporation[s] or foreign corporation[s] that [are] publicly held corporation[s], whose principal executive offices, according to the corporation’s SEC 10-K form, are located in California.” Companies that violate the new law will initially face a $100,000 penalty, and fine of $300,000 for a second or subsequent violation.

There is more to the Bill, though. By the end of 2021, companies with boards of five directors will also be required to have at least two women on their boards, while companies with six or more directors on their boards will be required to have at least three women directors. These additional thresholds will affect a significant number companies based on public boards’ current composition.

Only 11 percent of California-based companies currently meet the 2021 requirements

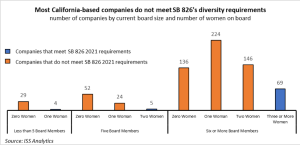

Based on ISS Analytics data, we have identified 689 public companies profiled by ISS that currently have their executives’ offices in California and would, as a result, be subject to SB 826’s requirements. We have also identified 8 companies incorporated in California, but with headquarters in a different state, where the law may also apply. However, we have only focused on the state where companies are headquartered for the purposes of this analysis. The data is based on ISS’s most recent board profiling of 4,471 active public companies that held at least one annual meeting since January 2017. Of the 689 companies with their executive offices in California, only 78 companies (11 percent) are fully-compliant with the 2021 requirements of the new law.

Currently, approximately one-third of California-based companies (217) lack any female director representation and will have to appoint at least one female on their board by the end of 2019.

Considering SB 826’s additional requirements for the end of 2021, only 69 of 575 companies with six or more board members have at least three female directors on their boards per the new mandate. Among the 81 companies with five directors on their boards, only five companies meet the requirement of having at least two women directors. Finally, only four of the 33 companies with a board size of less than five board members have at least one woman on their board. In total, 199 companies will need to appoint at least one female director by 2021, while 276 companies will need to appoint at least two female directors, and 136 companies will need to appoint at least three female directors.

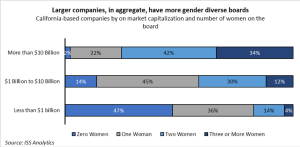

SB 826’s mandates will have an immediate impact on small and medium-sized companies. Of the 114 companies with a board size of 5 seats or less, 71 percent of companies currently have zero female representation and therefore do not meet the 2019 requirement. Among companies with 6 or more board members, only 29 percent do not comply with the 2019 requirements. Looking at company size based on market capitalization, 47 percent of the companies with a market cap of less than $1 billion do not comply with the 2019 mandate. Nevertheless, the law will have an effect on companies of all sizes two years later, as larger companies (in terms of board size) will have to include more than one woman on their boards. Currently, 66 percent of the companies with market capitalization greater than $10 billion do not have enough women on their boards to meet the 2021 mandate.

Is California lagging in board gender diversity?

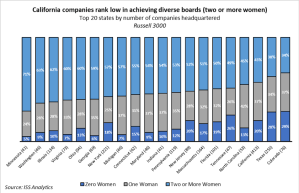

As California became the very first state in the U.S. to mandate female directorship on boards, one might ask whether gender diversity in the state is lagging compared to other states, as implied by the Bill’s authors. Among 2,578 reviewed Russell 3000 companies with headquarters in the U.S., 413 companies are based in California. Approximately 20 percent of these California-based companies have no women on their board, compared to 17 percent of all U.S.-based firms.

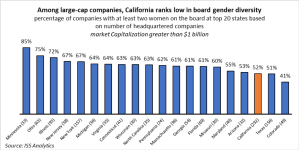

A state-by-state comparison reveals that California is currently ranked 38th among the U.S. states in terms of the percentage of companies that have at least two women on their board. Among the top twenty states in terms of the number of companies headquartered in the state, only Texas and Colorado have a lower percentage of companies with at least two women on their boards than California.

Controlling for size, the results are similar, as California ranks 37th among U.S. states in terms of the percentage of large-cap companies (market capitalization greater than $1 billion) with at least two women on the board. California’s relative low board gender diversity appears to correlate with a high concentration of specific sectors in California’s economy. The Informational Technology and Health Care sectors, which account for more than half of the public companies in the state, also happen to have relatively lower gender diversity levels compared to other sectors.

The California mandate alone could lead to 22-percent increase of U.S. female directorships by 2021

While California will become the first state to introduce a gender quota in the U.S., such an initiative is far from uncommon in other countries. Since Norway passed a quota requiring all public company boards to have a gender balance of at least 40/60 into law in 2007, many European countries have followed suit and adopted similar requirements. The European Commission has even proposed to require minimum 40-percent gender balance for non-executive directors. The specifics of female mandates vary by country. Some have legislative quotas with penalties involving fines for violations (Belgium, France, and Italy). In Norway, firms that fail to meet gender balance requirements may face even more severe consequences. Other countries have mandates that may be without sanction (such as in Germany) or apply on a comply-or-explain basis (Netherlands). One thing is certain – countries that have introduced gender diversity targets have seen the number of women on their company boards rise dramatically.

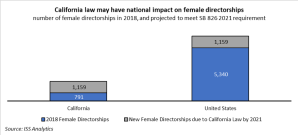

Assuming all companies meet the requirement while maintaining the same board size by 2021, women are expected to occupy at least 1,159 new public company board seats. This is a significant increase, considering that the 689 companies located in California currently have only 791 directorships held by female directors. The increase of directorships held by women because of the new law alone would more than double female directorships in California and could lead to an approximately 22-percent increase of female directorships nationwide.

Potential legal challenges

The new law faces opposition by the California Chamber of Commerce and other business groups in the state and may be challenged in the courts. When signing the law, Governor Jeff Brown admitted that he did not “minimize the potential flaws that indeed may prove fatal to [the law’s] ultimate implementation.” In their letter to the state senate opposing the bill, the coalition of business groups cited three key concerns.

- SB 826 considers only one element of diversity. The group argues that the law elevates gender diversity as a priority over other aspects of diversity and protected classifications recognized under U.S. law.

- SB 826 violates the U.S. Constitution, California Constitution, and Civil Rights Law. The opponents to the law argue that, if there are no vacancies on the board and shareholders have not approved an increase in board size, companies would have to displace current male directors solely based on gender. In addition, the law would lead companies to discriminate based on gender in the director hiring process.

- SB 826 Conflicts with the Internal Affairs Doctrine of Corporations Code Section 2116. According to the opponents, the internal affairs doctrine appears to dictate that the laws of the state of incorporation apply for actions involving the internal affairs of a corporation.

If a legal challenge does ensue, the outcome would depend on the courts’ interpretation of the mandate itself as well as the laws and regulations its opponents claim it contradicts. Nevertheless, regardless of the outcome, the law is expected to enhance the existing momentum towards greater gender diversity at U.S. boards.

Diversity beyond the boardroom

In a February 2018 Governance Insights publication, ISS attempted to predict the trajectory of female directorships in the future. Given the prior rate of change, ISS predicted that one-third of Russell 3000 new director nominees would be women by 2022. However, rapid market developments driven by investor engagement and voting policies, as well as greater awareness of gender inequality and the #metoo movement, have outpaced those original predictions. One-third of new director appointees at Russell 3000 companies were women in 2018, and we expect this number to increase in the coming years, as board gender diversity gains more support in the market. SB 826 would certainly add to the impetus towards change.

If experience from other markets serves as a guide, gender quotas do not necessarily result in gender equity at the rest of the organization. Another ISS study found that the percentage of women CEOs at markets that have maintain gender quotas on boards remains disappointing low – in the single digits – even at markets that have achieved board gender diversity above 30 percent of directorships (e.g. in Sweden and Germany, only 2 percent of CEOs are women). As such, California should avoid the risk of board gender diversity becoming a check-the-box exercise for boards without further improvements in diversity and inclusion in the entire organization.

Companies should be incentivized to improve diversity beyond the board. In fact, greater diversity in the C-Suite appears to translate in economic returns. ISS’s more recent publication on C-Suite diversity and company performance found that companies with at least two female named executive officers outperformed their peers in profitability and risk management regardless of the CEO’s gender. Companies where the CEO was the sole female executive underperformed their peers, which suggests that the diversity of teams is the ultimate driver of performance, instead of the gender of any particular individual. Similar trends of superior profitability and better risk management were observed for companies that combined gender diversity in the C-Suite with gender diversity at the board.

This post comes to us from Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS).

Sky Blog

Sky Blog

The main conclusion from above is that “Of the 689 companies with their executive offices in California, only 78 companies (11 percent) are fully-compliant with the 2021 requirements of the new law.”

Keith Paul Bishop, http://www.calcorporatelaw.com/iss-staffers-publish-questionable-conclusions-regarding-californias-new-gender-quota-law, has some concerns about this conclusion:

There are several reasons to be suspicious of this conclusion. As an initial matter, they do not explain how they determined compliance. The SEC currently does not require companies to disclose the gender of their board members. Reliance on directors’ given names is likely to be inaccurate. Many given names (e.g., Glenn, Kim and Terry) are not exclusive to either gender. Additionally, California’s law defines “female” as “an individual who self-identifies her gender as a woman, without regard to the individual’s designated sex at birth.” Cal. Corp. Code § 301.3(f)(1). Thus, the only way to accurately determine whether a director is a female is to ask that director.

More importantly, the new law applies to corporations with “outstanding shares listed on a major United States stock exchange”. Cal. Corp. Code §§ 301.3(f)(2) & 2115.5(b). While the legislature left it to others to determine what makes a stock exchange “major”, it clearly excluded (i) corporations with shares traded in the over-the-counter markets (such as the OTC Bulletin Board), (ii) corporations having only other types of securities (such as American Depositary Shares and bonds) listed on a major U.S. stock exchange, and (iii) companies with securities listed on a major U.S. stock exchange that are not organized as corporations (such as limited partnerships and real estate investment trusts). The staffers say only that they identified 689 “companies” and make no mention of the fact that the statute applies only to corporations with shares listed on a major U.S. stock exchange. Thus, I am suspicious that the 689 “companies” includes some, if not many, companies not subject to California’s new statute.

It would be great if the authors could respond to Keith’s concerns.

Bernie