Cyber risk is a major concern to corporations and investors. Recent academic studies point out that firms suffer large negative returns when they disclose that they have suffered a data breach (e.g., Akey, Lewellen and Liskovich (2018) and Kamiya et al (2019)) and that informed market participants are able to trade on this information before it becomes public (Mitts and Talley (2018)). These studies and many articles in the popular press often consider these events to be idiosyncratic. However, cyber risk can also contribute to aggregate information risk since the current financial system entrusts information to several centralized custodians that can fail to keep that information secure.

In a recent paper, we use a sophisticated newswire hacking scandal to explore some of the financial-market implications of an aggregate shock to information security. From 2010 to 2015, a group of Russian and Ukrainian hackers illegally breached the IT systems of several large newswire companies. At different times, they were able to access earnings announcements of firms that distributed press releases through the three largest newswire companies: PR Newswire, Business Wire, and Marketwired. While earnings are typically released overnight, firms provide earnings announcements to newswire services during normal market hours, often in the morning. These announcements are typically uploaded to newswires’ IT systems at least several hours before the news is released publicly, which in this instance gave the hackers several hours to access, interpret, and trade on the information. This ring of traders aggressively traded in the hours before the news was publicly released in order to exploit this private, “inside” information. Eventually, in 2015, the newswire companies and the SEC were able to identify and prosecute the hackers that resided in the United States.

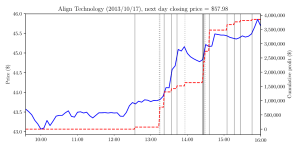

We use publicly available court documents to identify the timing of these hacks. For a small set of cases, we have information about the individual trade quantities and times of specific trades. In Figures 1a and 1b, we illustrate two examples of their trading strategies on the day when the earnings news was uploaded but had not yet been released and their two-day dollar profits. The solid blue line plots the stock price over the day. The vertical solid gray bars indicate trading in the stock by the traders, while the dotted gray bars indicate trading in derivatives by the traders. The dotted red line tabulates the cumulative trading profits associated with taking a position at a given time and holding it until the close of the next day. These figures illustrate that the traders profited on both positive and negative news by taking appropriately bullish or bearish positions in both equities and derivatives. In contrast with most inside trades that typically yield small dollar profits (Cziraki and Gider (2018)), these hackers earned large profits, collectively in excess of $100 million, including several that yielded more than $1 million over two days.

Figures 1a and 1b

We use this setting to study two questions. First, how quickly can trades reveal private information possessed by a small group of retail traders? Second, how well do existing measures of informed trading detect this behavior?

We answer the first question by studying how stock prices react once the earnings news becomes public during the overnight market. We find that overnight returns of firms whose newswires had been hacked are less responsive to earnings news. Specifically, we relate the overnight stock return to the “earnings surprise” that a firm releases in time periods when a firm’s newswire was subject to a hack and compare this relationship with time periods when its newswire was not subject to a hack. If the hackers’ trading revealed non-public information to markets in the afternoon when they were illegally trading using this information, we would expect that overnight stock returns would be less responsive to a given earnings surprise in a hacked period.

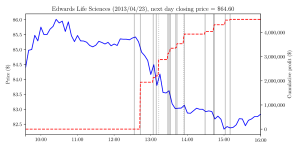

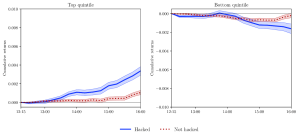

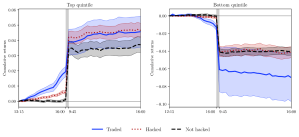

Figures 2a and 2b below present this effect graphically. Specifically, in Panel A, we plot the cumulative returns around earnings announcements for firms exposed to hacks (the solid blue line) and not exposed to hacks (the dashed red line) from noon on the trading day before the announcement to the close on the next trading day. The left panel shows returns for the largest quintile of earnings surprises while the right panel shows returns for the smallest quintile of earnings surprises. In both cases, we observe a significant price drift towards the post-announcement price in the hours before the announcement for firms exposed to hacks, which suggests that some information regarding the unreleased news is incorporated into prices. By the end of the next trading day, there is no significant difference between firms that have been hacked and those that have not, which means that the total response to earnings news is the same. Panel B presents the same figures but zooms in on the pre-announcement price drift. Using linear regression analysis, we find that a firm’s overnight return is 15 percent less responsive to news when its newswire was subject to a hack.

Figures 2a and 2b

Our analysis so far only uses information about the ability of traders to access material, non-public information, not actual, known cases of trading on that information. This means that the effect we show above is likely to represent a lower bound of the price impact of trades on inside information. Unfortunately, the entire set of cases where the hackers were likely to have engaged in such trading is not publicly available, but we were able to identify nearly 400 events that the SEC used to build their cases against the ring of traders and use these events to show how much larger this price impact could be. In order to do so, we match each known event of trading on inside information to 10 potential events (five earnings releases from the set of newswires that were subject to a hack in the same quarter but not part of an SEC case and five earnings releases from the set of newswires that were not subject to a hack in the same quarter).

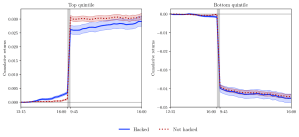

Figure 3 presents results of this analysis. The solid blue line (“Traded”) plots the returns for firms that formed the basis of the SEC’s case, the dotted red line (“Hacked”) plots the returns of firms that were subject to trading on inside information but did not form the basis of this case, while the dashed black line (“Not hacked”) plots the returns of firms that were not subject to potential cases of trading on inside information. These results confirm that the price discovery effects in the cases that formed the basis of the SEC’s case are substantially larger than what we previously documented. Moreover, there appears to be price discovery effects on some of the cases where there could have been trading on inside information (shown by the “Hacked” line) but was not part of the SEC’s case. This most likely represents trading by the hackers or their affiliates that was not disclosed in public court documents.

Figure 3

We next ask how well the commonly used empirical measures of trading on inside information in financial markets were able to detect this trading. Three categories of measures have been proposed by academic researchers to identify periods with such trading: volume-based measures, liquidity-based measures, and order imbalance-based measures. We find that volume-based measures, specifically share turnover, intra-day volatility, and trading volume, and effective spreads by liquidity providers are all substantially higher when the hacker affiliates were likely to be trading. In contrast, measures of such trading based on trading imbalance do not detect this activity.

Finally, we conclude by providing some evidence on how the hackers’ information made its way into prices. We examine whether liquidity providers or high-frequency traders (HFTs) were possibly able to infer the presence of increased trading and “lean with the wind” (Van Kervel and Mankveld 2019) by increasing their own trading volume. We find that professional trading volume was more responsive to “retail” trading volume at times when the hackers were likely to be trading than at other times. While this evidence is somewhat speculative, it seems that HFTs amplified the effect of the hackers’ individual trades, potentially making it easier for regulators to detect them.

Our research highlights a new impact of cyberattacks. We show that in addition to being a source of risk for individual firms, cyber risk can have aggregate consequences for capital markets. In our setting, companies relying on a newswire provider to disseminate corporate press releases were exposed to the cyber intrusion of their newswire providers. We show that these cyberattacks allowed a group of traders to profit from illegally obtained material, non-public information over a period of six years. This is not an isolated incident. The same group of hackers was able to orchestrate a similar cyberattack on the SEC’s EDGAR platform in 2017. Thus, we believe that information risk may be increasing as the cyberattacks become more sophisticated.

REFERENCES

Akey, Pat, Lewellen, Stefan, and Inessa Liskovich, 2019, Hacking corporate reputations, University of Toronto working paper

Cziraki, Peter, and Jasmin Gider, 2018, The dollar profits to insider trading, University of Toronto working paper.

Shinichi, Kamiya, Kang, Jun-Koo, Kim, Jungmin, Milidonis, Andreas, and Rene Stultz, 2019, What is the impact of successful cyberattacks on target firms? Journal of Financial Economics, Forthcoming.

Mitts, Joshua, and Eric L. Talley, 2018, Informed trading and cybersecurity breaches, Harvard Business Law Review, 8.

Van Kervel, Vincent, and Albert J Menkveld, 2019, High-frequency trading around large institutional orders, The Journal of Finance. Forthcoming.

This post comes to us from professors Pat Akey at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, Vincent Gregoire at HEC Montreal, and Charles Martineau at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management. It is based on their recent article, “Price Revelation from Insider Trading: Evidence from Hacked Earnings News,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog