On September 26, 2019, the SEC released the much-anticipated new rule and form amendments designed to modernize the regulation of Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs).[1] Rule 6c-11 under the Investment Company Act permits ETFs that satisfy certain conditions to operate without the expense and delay of obtaining an exemptive order from the commission under the act – and it is most welcome.

There is something fascinating about this initiative. What started 28 years ago as a way to avoid the taxation of mutual funds has avoided extensive SEC regulation. Now, there are about 3,000 U.S. ETFs with a total value of $3.36 trillion. They represent 16 percent of total global assets under management. The global numbers are $5 trillion for 6,000 ETFs.

With the diversity and size of this market comes a question: Could ETFs as an asset class raise liquidity concerns during a financial crisis? The 2008 crisis does not offer much guidance. Before the crisis, there were fewer than 1,000 funds representing $100 billion in assets under management. What if unexpected liquidity shortfalls hit again? In a recent report, Moody’s states that “unexpected market liquidity shortfalls could be most pronounced within ETFs tracking inherently illiquid markets, such as high-yield credit. These ETF-specific risks, when coupled with an exogenous system-wide shock, could in turn amplify systemic risk. ETFs targeting illiquid instruments, such as corporate bonds and leveraged loans, would present greater risks, and investors trading on the premise that ETFs are more liquid than their baskets may find that results fall short of expectations in a stressed environment.”[2]

This post looks at the risks represented by this asset class, which has evolved largely from a small-scale, tax-advantageous investment to the most main-stream investment instrument for asset managers, trading, and hedging while being largely held by individual investors.

A heavily concentrated market, dominated by retail investors

The backbone of the ETF markets is BlackRock, with 37 percent, of the market, followed by Vanguard, with 19 percent, and State Street, with 12 percent. This high level of concentration (68 percent) in three hands could be seen as a strength for the market, but also a possible vulnerability at times of crisis. Together, these asset managers control $2.5 trillion out of the total of $3.4 trillion ETF assets. Can these large asset managers handle a wave of redemptions fast enough, without provoking a market downfall?

ETFs under the Investment Company Act

ETFs are unquestionably similar to mutual funds: collective investment vehicles in underlying financial assets. Yet their inclusion of illiquid assets (like loans and credits) and questionable assets (crypto assets and leverage) led the SEC to limit the scope of ETFs that can be registered under the act. Now that a modernized regulatory framework is in place, we can examine the structure that might have unintended consequences.

In terms of liquidity, there are differences that make mutual funds (especially index funds) less competitive than ETFs. The lower fees of ETFs are one. The other is the obligation of mutual funds to hold cash reserves to face redemptions that structurally hampers their performance compared with ETFs. The Net Asset Value (“NAV”) of ETFs is structurally closer to the value of their basket of assets.

The primary liquidity risk

On August 24, 2015, however, some of the major U.S. ETFs diverged from their NAV by up to 50 percent, creating significant losses for investors. The liquidity of ETFs depends upon the ability of their issuers to sell ETFs at a price close to the price of their. The redemption system of ETFs is different from mutual funds. In the case of mutual funds, the fund managers are the counterpart of any seller, and the value of that repurchase is based on the Net Asset Value of the fund at the closing of the market. The seller can therefore sell with the certainty of being redeemed, but at an uncertain price.

For ETFs, there is no real counterparty to the sale other than the market itself. ETFs are listed on an exchange and trade like a stock, even though they are not representing a company but a portfolio.

This difference is often underestimated. ETFs can also be redeemed but only by financial firms assigned by the ETF manager itself. Specialized intermediaries called authorized participants (APs) transact directly with the ETF issuer to create and redeem ETF shares: New ETF shares are issued if demand is high or existing shares are withdrawn if supply is too great. This helps to keep an ETF’s price in line with the value of its underlying assets by removing the influence of supply and demand on the fund.[3]

This raises a regulatory question: Since the ETFs are listed on regulated exchanges, shouldn’t the rules of issuance include some investor protections such as a minimum number of owners? Should that be realized through ETF IPOs? That would put the ETFs half way between the Investment and the Exchange acts. This is the reason for approval on July 22, 2016, of generic listing standards by the SEC under the Securities Act of 1934.[4]

If there is no purchaser of ETFs during a financial crisis, there is a risk that the ETFs become like a closed-end fund, with the ETF promoter unable to redeem ETFs because of the impossibility of selling underlying assets.

The secondary liquidity risk

The secondary liquidity risk of ETFs relates to whether their underlying assets can be sold on the market, which is key to the ETF issuer’s ability to redeem the ETFs. Let’s look at the most important ETF: the “spider” (SPY) or S&P 500 index ETF with over $300 billion of market value.

Why should we worry about the secondary risks?

- With 500 underlying shares, it is highly diversified, but liquidity is not arithmetically distributed. Companies with small market capitalization are more often subject to liquidity problems. It is one of the reasons why the exchanges limit the increase or decrease of a stock over one day.

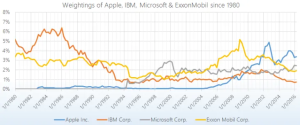

- As of January 2020, Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and Facebook account for 17.5 percent of the S&P 500, creating risk of overexposure to passive investors. [5]

- A sector crisis like the dot.com crisis of 1989 can create a freezing of liquidity and threaten the ability of the ETF issuer to redeem sales of the ETF because of specific components of the underlying portfolio.

- A massive sale of ETFs will create a crisis in the liquidity of the ETF and the liquidity of its assets

The role of the SEC: Investment Act and Exchange Act

The listing standards for ETFs on exchanges are subject to SEC approval under the Exchange Act. The SEC was well advised to monitor the bid and offer prices of ETFs as a measurement of their liquidity (or lack thereof) as well as their volumes. There is no reason why a listed security on an exchange should not provide the same transparency as stocks and shares. However, does a monthly average provide enough warning of a possible liquidity problem?

As indicated in the rule, the SEC pursues both operational improvements and investor protection. The unusual issuance and trading structure of ETFs could lead, in the absence of such transparency, to difficulty for investors to assess the liquidity risk they are taking.

The similarity to an open-end fund has its limits: Investors might be put in a position where the only resort might be ETF liquidations. As indicated by the SEC, this risk must be monitored at least as seriously as individual securities and the commission will do so through the Exchange Act and the Investment Act. It is not appropriate to build a market that looks like a casino where funds disappear on a regular basis.[6] Size matters: The funds that have closed each totaled between $2.4 million and $ 78.8 million. If these were normal stocks, they would not be authorized to be listed with such low values and capitalizations, thereby creating accrued risks of a liquidity squeeze. Many ETF issuers are, themselves, small and unable to handle redemptions.

Making ETFs simpler might be dangerous, leading to the multiplication of zombie or fake ETFs. The SEC and the exchanges have to envisage a stricter level of standards for the ETF issuers, the authorized participants, and the size of the ETFs. Maybe ETFs should not be allowed to benefit from the 6c-11 rule and an exchange listing before reaching a minimum size and level of activity.

It was wise not to include leveraged/inverse ETFs among those authorized under Rule 6c-11. Among the ETFs, given that they would double the liquidity impact and make the market more volatile. We should not forget that retail investors see in ETFs diversification that would lead to more stable returns and yields.

The authorization for open-end funds to lend securities[7] might represent a risk that investors are not aware of and could increase the volatility of the fund independently of its assets.

A quarter of the ETFs have closed since 2014.

Invesco has been at the forefront of the closing of ETFs. In December 2019 the firm announced that it would liquidate 42 ETFs by February 2020, on top of the 19 it already closed. Among the 3,000 funds in circulation, there is a category called “zombie ETFs,” of which 58 were liquidated in the first half of 2019. Aberdeen Standard Investments announced the closing and liquidation of Aberdeen Standard Bloomberg WTI Crude Oil (AOIL). DWS Group announced on October 24 the liquidation of five Xtrackers ETFs.

The fact that open-end ETFs are qualified as redeemable securities opens an avenue that is similar to open-end funds, but there is an automatic aspect to the redemption process, i.e. the sale of the underlying shares in proportion to the ETFs redeemed by the ETF issuer. The dual exit (sale on the market and redemption) highlights the primary and secondary risks.

The risk of ETFs in a financial crisis

In the event of a financial crisis, these risk will compound: The price of ETFs will go down, and authorized participants will seek redemption, forcing the sale of underlying assets. This dual liquidity might translate into dual volatility.

Investors may be in for a nasty surprise if and when their ETF’s liquidity profile starts to mirror that of its underlying assets, particularly in the less liquid fixed income markets.[8]

Many professionals have warned of a potential ETF liquidity crunch trapping investors in products they can’t exit. Thus, if the markets start to decline, and general panic spreads among ETF owners, a huge wave of selling engulfing the entire market can follow, quickly turning a modest sell-off into an avalanche.[9]

Should market regulators be considering systemic market risks?

This review is not exhaustive but raises a few questions that regulators (and not just the SEC) might need to address. It means that there is an increased – if unlikely – tail risk of a disorderly sell-off in the market. ETFs have the potential to exacerbate broader liquidity problems in securities markets. The concern is that if investors were to sell out of an ETF en masse, this could increase the chance of fire sales of the underlying security, which could affect financial stability.[10] A few questions we should ask:

- Are the listing criteria under the Exchange Act for ETFs consistent with the criteria that individual securities are subject to?

- In view of the role of ETF issuers in the issuance and redemption process, should they be subject to criteria similar to those applicable to other open-end funds?

- Are the liquidity risks of ETFs generally taken into consideration in the approval of specific ETFs? Should the systemic risks of ETFs be addressed specifically, given their primary and secondary impacts?

- Should the concentration of the ETF market in three financial institutions be a source of comfort or concern?

- Should ETFs whose underlying assets are not securities be excluded from rule 6c-11 for reasons of liquidity risks?

This goes beyond the purpose of rule 6c-11, but the rule creates a regulatory framework that can be a starting point for addressing specific risks associated with ETFs, a significant source of concern for market observers.

ENDNOTES

[1] https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2019-190

[2] https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b1fbh1j3819g21/The-Big-Risk-Lurking-in-ETF-Markets

[3] https://www.ipe.com/observations-on-etf-liquidity/10013218.article

[4] https://www.sec.gov/rules/sro/bats/2016/34-78396.pdf

[5] https://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/28/sp-500-dominated-by-apple-microsoft-alphabet-amazon-facebook.html

[6] https://www.etf.com/etf-watch-tables/etf-closures

[7] https://www.barrons.com/articles/etfs-hidden-source-of-returnsecurities-lending-1523054918

[8] https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b1fbh1j3819g21/The-Big-Risk-Lurking-in-ETF-Markets

[9] https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/active-mutual-funds-liquidity-risk-crisis-etfs/

[10] https://www.ft.com/content/a1deabc2-3eab-11e9-9499-290979c9807a

This post comes to us from Georges Ugeux, who teaches international finance at Columbia Law School. As group executive vice president of international and research at the New York Stock Exchange, he was deeply involved in the launching of the first NYSE ETF, the iShares Global 100 ETF.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog