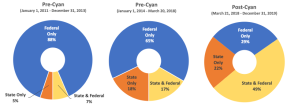

It has been two years since the Supreme Court’s decision in Cyan v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund[1] permitted securities class actions alleging violations of the Securities Act of 1933 to be litigated in state courts nationwide. The court recognized that, in enacting the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (SLUSA), Congress apparently intended to withdraw jurisdiction over Securities Act cases from state courts, but it held unanimously that the terms of SLUSA failed to accomplish that goal. The result, as shown in Figure 1, has been a dramatic increase in the volume of state-filed ’33 Act cases – and, in particular, cases litigated simultaneously in both state and federal courts. Nearly all of these cases alleged violations of Section 11 of the Securities Act, so for simplicity we will refer to this litigation as “Section 11 litigation.”

Figure 1: Forum Mix in Securities Act Cases Filed 2011 Through 2019

Source: Stanford Securities Litigation Analytics, https://sla.law.stanford.edu/.

The Stanford Securities Litigation Analytics (SSLA) project has collected data on state Section 11 litigation from 2011 (federal cases from 2000) to the present. A more detailed analysis of the data can be found here.

There are two concerns with litigating Section 11 cases in state court. First, state courts generally do not provide the same procedural protections that federal courts apply to Section 11 claims. Federal courts follow the relatively strict Twombly–Iqbal pleading standard, which governs motions to dismiss, and the mandatory stay of discovery provided for by the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA). Without these procedural protections, plaintiffs’ attorneys may file weak cases in state court in the hope of pressuring defendants to settle. Second, if a plaintiffs’ attorney can bring a suit in state court, there is nothing to stop another from bringing the same case in federal court, thereby imposing on defendants the burden of litigating parallel cases simultaneously.[2] The data support these two concerns: Relatively weak cases are filed in state court, and parallel litigation in state and federal court has become common and appears to pressure defendants to settle.

On March 19, 2020, in Salzberg v. ,[3] the Delaware Supreme Court upheld the facial validity of charter provisions that require Section 11 claims against a company to be filed in federal court (“federal-forum provisions” or “FFPs”), thereby allowing the company to move to dismiss a suit in state court. The Sciabacucchi case will mitigate the impact of Cyan. To the extent other state courts accept the validity of FFPs in Delaware corporate charters, they will dismiss Section 11 cases filed against Delaware corporations with FFPs.

The Sciabacucchi case, however, does not spell the end of Section 11 litigation in state courts. First, the Delaware Supreme Court only upheld the facial validity of FFPs, and thus left open the possibility that Delaware courts will find FFPs invalid in particular contexts. Second, there is no assurance that other states will accept the validity of FFPs in the charters of Delaware corporations, facially or as applied. We could therefore find ourselves back in the pre-Cyan situation, where some states recognize FFPs as valid and some do not – and where plaintiffs’ attorneys understandably try to file cases in states that find them invalid. Third, at this point, FFPs have not been validated for companies incorporated in states other than Delaware. Accordingly, federal legislation that accomplishes what Congress intended to accomplish in SLUSA would be the most effective way to address the problems we document when Section 11 cases are litigated in state court.

Weak Cases Filed in State Court

Comparing ‘33 Act cases filed solely in state court with those filed solely in federal court, we find that a roughly equal percentage settle. But plaintiffs in state cases recover a lower percentage of statutory losses than do plaintiffs in federal cases.[4] This suggests that cases filed in state court are weaker than those filed in federal court. The difference is especially stark among settlements that occurred after a motion to dismiss was denied. The mean and median recoveries in federal cases were 37.3 percent and 20 percent, respectively, and in state cases the mean and median recoveries were 12.6 percent and 11 percent. This suggests not only that weaker cases are filed in state court, it confirms that state court rulings on motions to dismiss do not screen out weak cases as well as federal court rulings do.

Parallel Litigation in State and Federal Court

The increase in parallel litigation in state and federal court is the most wasteful consequence of Cyan. As shown in Figure 1, from the time Cyan was decided until December 31, 2019, nearly half of all ‘33 Act litigation consisted of parallel pairs of cases in state and federal court. This is a conservative estimate, as additional cases may have been, or still may be, filed that are a parallel counterpart to a state or federal case filed prior to that date.

Parallel litigation is not only inefficient, it also increases the pressure on defendants to settle a non-meritorious case. The data support this concern. From 2011 through 2019, 84 parallel pairs of cases were filed (51 post-Cyan), and 28 pairs have been resolved in both state and federal courts. Of the 28 resolved pairs of cases, only fivewere dismissed or dropped in both state and federal court. The remaining 23 cases settled in one or both courts. That is, 82 percent of parallel pairs settled, compared with 67 percent of cases filed solely in state court and 65 percent of cases filed solely in federal court.

State ‘33 Act Litigation in The Future

Although Sciabacucchi will reduce the volume of state Section 11 litigation, it remains to be seen by how much. Federal legislation to withdraw state jurisdiction over Securities Act cases is still warranted.

In the meantime, there are some hopeful signs that at least some state courts will manage Section 11 cases in ways that mitigate their costs. In California, which has denied motions to dismiss in 88 percent of its Section 11 cases, one court has recently taken a different approach in light of Cyan. In In re Natera Securities Litigation,[5] Judge Buchwald exercised judicial notice to a greater extent than a California court ordinarily would in dismissing a case. He explained:

[T]he Court believes that it has the discretion . . . to treat the pending Motion as would a Federal trial court when hearing and deciding a Rule 12(b) Motion to Dismiss . . . .

Using this Federal motion procedure is also now even more warranted in the wake of the recent United States Supreme Court decision in Cyan, Inc. v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund (2018) 138 S. Ct. 1061 . . . . This recent confirmation of concurrent jurisdiction would appear to call for some consistency and uniformity in the handling of such cases as between the Federal and State Courts.[6]. . . .

Similarly, in In re Dentsply Sirona Shareholder Litigation,[7] Judge Scarpulla dismissed the case, quoting federal courts applying the Twombly–Iqbal pleading standard.

There are also rays of hope with respect to discovery stays. As of December 31, 2019, New York courts granted four out of eight motions to stay discovery. In In re Everquote, Judge Borrock held that “[t] he simple, plain, and unambiguous language [of the PSLRA] expressly provides that discovery is stayed during a pending motion to dismiss ‘[i]n any private action arising under this subchapter.’”[8] In In re Greensky, Judge Schecter held that while the PSLRA’s mandatory stay may not apply in state court, the underlying purpose of the stay should be taken into account, and on that basis she granted the stay.[9]

There is even some hope that state courts will reduce the burden on defendants of litigating the same claims in state and federal court. About half the state courts that have considered the issue have granted stays either pending resolution of the parallel federal case or pending a ruling on a motion to dismiss in the federal case.[10]

However, neither of these responses to Cyan – a federal forum charter provision or adjustments to state court procedural rules – will eliminate the inefficiency created by allowing state courts to hear Securities Act cases. The appropriate response, therefore, is for Congress to do what it intended to do in SLUSA – simply withdraw state jurisdiction.

ENDNOTES

[1] 138 S. Ct. 1061 (2018).

[2] We define a pair of state and federal cases as parallel when both cases include a cause of action based on the same alleged misstatement or omission in the defendant’s registration statement.

[3] Salzberg v. Sciabacucchi, No. 346, 2019 (Del. Mar 18, 2020).

[4] Statutory losses are measured as the difference between a defendant’s IPO price and its share price at the time the law suit is filed.

[5] No. CIV537409 (Cal. Super. Ct. filed Mar. 24, 2016).

[6] Memorandum of Decision and Order at 4–5, In re Natera Sec’s Litig., No. CIV537409 (Cal. Super. Ct. Aug. 7, 2018) (No. 1309959).

[7] No.155393/2018 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. filed June 7, 2018)

[8] See Decision and Order at 11, In re Everquote, Inc. Sec. Litig., No. 651177/2019 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Aug. 6, 2019) (No. 73).

[9] See Decision and Order at 3, In re Greensky, Inc. Sec. Litig., No. 655626/2018 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Nov. 25, 2019) (No. 91).

[10] See, e.g., Decision and Order on Motion at 12–13, Mahar v. Gen. Electric Co., No. 653648/2018 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Oct. 15, 2019) (No. 155) (stay pending resolution of federal case); Order Re: Motions to Stay at 4–5, In Re Arlo Techs., Inc. S’holder Litig. No. 18cv339231 (Cal. Super. Ct. Jun. 21, 2019) (No. 3037496) (same); Order Granting Motion for a Stay of Proceedings at 1, Reyes v. Zynga Inc., No. CGC12522876 (Cal. Super. Ct. Aug. 26, 2013) (No. 001C04178178) (stay pending federal court ruling on motion to dismiss); Order, Rajasekaran v. Cytrx Corp., No. BC541426 (Cal. Super. Ct. Oct. 14, 2014) (same). Half the courts have denied the motion. See, e.g., Order After Hearing on October 25, 2019 at 6–8, Franchi v. Cloudera, Inc., No. 19CV348674 (Cal. Super. Ct. Oct. 29, 2019) (No. 3580010); Decision and Order on Motion at 2–3, Hoffman v. Stephenson, No. 650797/2019 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Jun. 24, 2019) (No. 89) (involving issuer defendant AT&T Inc.); Decision and Order at 7–12, In re PPDAI Grp. Sec. Litig., No. 654482/2018 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Jul. 5, 2019) (No. 91); Order Denying Venator and Huntsman Defendants’ Motion to Stay Under Doctrine of Comity at 1, Macomb Cty. Emps. Ret. Sys. v. Venator Materials PLC, No. DC-19-02030 (Tex. Dist. Ct. Sept. 3, 2019).

This post comes to us from Michael Klausner, Jason Hegland, Carin LeVine, and Jessica Shin at Stanford Law School. It is based on their recent article, “State Section 11 Litigation in the Post-Cyan Environment (Despite Sciabacucchi), available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog