Two decades ago, Congress repealed the Glass-Steagall Act’s Depression-era separation between commercial banking and other financial activities, paving the way for bank holding companies (BHCs) to expand into investment banking and insurance. At the time, some critics – most notably, Professor Arthur Wilmarth – warned that financial conglomeration would encourage BHCs to exploit their depository institutions’ “federal safety net.”

Critics were correct to suspect that financial conglomerates might take advantage of their bank subsidiaries by transferring government subsidies to their nonbank affiliates. Banks enjoy many forms of government support. For example, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation guarantees bank deposits, providing a reliable and cheap source of funding for insured institutions. Banks may access the Federal Reserve’s discount window for liquidity. And banks perceived as systemically important obtain market funding at artificially low rates because creditors believe the government would not allow them to fail. Collectively, this federal safety net provides a valuable subsidy to insured depository institutions. In the absence of Glass-Steagall’s structural separations, a bank’s nonbank affiliates could avail themselves of this subsidy through preferential loans, asset sales, or other intra-company transactions.

Exploitation of bank subsidiaries by their parent holding companies is problematic for several reasons. When a bank transfers its federal safety net to a nonbank affiliate, it extends the scope of government subsidies and encourages the affiliate to take excessive risks. Moreover, expanding the federal safety net to nonbank affiliates distorts competition with rival firms that are unaffiliated with a depository institution and therefore do not receive comparable subsidies. Further, unsound loans to or asset purchases from a nonbank affiliate may impair a bank’s financial condition, threatening its depositors and other creditors.

As a first line of defense against these risks, policymakers instruct a bank’s board of directors to shield the bank from exploitation by its affiliates. Bank regulators, for example, tell bank directors to “ensure that relationships between the bank and its affiliates … do not pose safety and soundness issues for the bank….” Regulators further instruct a bank’s board to “ensure the interests of the bank are not subordinate to the interests of the parent holding company….” If the bank’s board is concerned that the holding company is engaged in practices that may harm the bank, regulators advise the directors to “dissent on the record” and “hire independent legal counsel.” Policymakers even require a bank’s board of directors to review and approve certain transactions with the bank’s affiliates. U.S. banking law, in sum, presumes that bank directors zealously safeguard the interests of the bank vis a vis its holding company.

My new article, “Who’s Looking Out for the Banks” – written for a symposium honoring Professor Wilmarth’s retirement – contends that these safeguards ignore a critical conflict of interest: The vast majority of large-bank directors also serve as board members of their banks’ parent holding companies. These dual directors are therefore poorly situated to exercise the independent judgment necessary to protect a bank from exploitation by its nonbank affiliates.

When a bank’s directors sit on the board of the bank’s holding company, the directors have an incentive to allow the holding company and its nonbank subsidiaries to take advantage of the bank and thereby benefit from federal safety-net subsidies. Since BHC directors are accountable to shareholders for maximizing the value of the financial conglomerate and not just of the bank subsidiary, they may want the bank to engage in preferential loans, asset transfers, or other intra-company transactions that benefit its affiliates. In addition, BHC directors are enriched financially when a bank extends federal safety-net subsidies to its affiliates, since board members are often significant shareholders of the BHC.

Consider the United States’ largest financial conglomerate, JPMorgan Chase & Co. Last year, 10 individuals, including chief executive officer (CEO) Jamie Dimon, served on the company’s board. Those same individuals comprised the board of the firm’s lead bank subsidiary, JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., of which Dimon also served as CEO. Thus, the 10 people who were responsible for safeguarding the bank’s $3 trillion in assets were, at the same time, in charge of maximizing the holding company’s value, including its $700 billion in nonbank assets. Since extending the bank’s federal safety net to its nonbank affiliates could improve the holding company’s performance, JPMorgan’s directors faced an inherent conflict of interest.

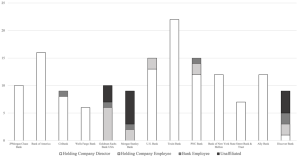

JPMorgan is not alone. I compiled a dataset of the directors of the lead bank subsidiaries of BHCs with more than $100 billion in assets and more than 1 percent of their assets in nonbanks. Figure 1 reveals that the vast majority of big-bank directors simultaneously serve as directors of their banks’ parent holding companies. More than half of the banks in the sample do not have a single director who does not also serve on the board of its BHC. Of the four biggest banks by asset size – JPMorgan Chase Bank, Bank of America, Citibank, and Wells Fargo Bank – only Citibank has a director who does not also sit on its BHC’s board. In total, 119 out of 152 bank directors in the sample – or 78 percent – simultaneously serve on the board of the bank’s holding company.

Figure 1: Bank Director Affiliations

I recommend that policymakers strengthen bank governance – and better insulate banks from their nonbank affiliates – by requiring at least some of a bank’s directors to be unaffiliated with its parent holding company. Mandating that a bank appoint directors who do not work for or otherwise represent the holding company would ensure that the bank’s board is equipped to look out for the depository institution when its interests conflict with those of its nonbank affiliates. I suggest a sliding scale: Financial conglomerates with significant nonbanking operations should maintain a majority of unaffiliated directors on their bank subsidiary boards, while conglomerates in which the bank is the dominant business could have fewer unaffiliated bank directors. In the interests of efficiency, this requirement should apply only to BHCs with more than $100 billion in assets and significant nonbank operations.

There is strong precedent, both internationally and domestically, for mandating that a depository institution’s directors be independent of its holding company. The United Kingdom, for example, requires that no more than one-third of a bank’s directors be employees or directors of the bank’s holding company or other affiliates. Even U.S. regulators have mandated unaffiliated directors for certain insured depository institutions. In 2021, the FDIC adopted a rule requiring each new industrial loan company (ILC) to limit its parent company’s board representation to less than 50 percent of the ILC’s directors “[i]n order to limit the extent of each [parent company’s] influence over a subsidiary industrial bank.” If such a rule is necessary to shield an ILC from exploitation by its parent company, a similar rule would be equally appropriate to limit conflicts of interest at other types of insured depository institutions, as well.

Scholars, including Professor Wilmarth, and policymakers such as Senator Elizabeth Warren have urged Congress to mitigate conflicts of interest within financial conglomerates by reinstating Glass-Steagall’s structural separation between commercial banking and other financial activities. These proposals merit serious consideration. In the meantime, the federal banking agencies should use their existing regulatory authority to limit financial conglomerates’ ability to take advantage of the federal safety net. By mandating that banks appoint directors unaffiliated with the banks’ holding companies, regulators could ensure that a bank’s board prioritizes the insured depository institution rather than the holding company. As long as commercial banks are permitted to affiliate with investment banks, insurance companies, and other nonbank firms, this governance reform is necessary to safeguard banks and limit the imprudent expansion of the federal safety net.

This post comes to us from Jeremy C. Kress, assistant professor of business law at the University of Michigan’s Stephen M. Ross School of Business. It is based on his recent article, “Who’s Looking Out for the Banks?,” available here and forthcoming in the University of Colorado Law Review.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog