Massive investment is required if mankind is to meet, and master, the challenges presented by global climate change. A recent report by McKinsey & Company posits that capital spending on energy and land-use infrastructure alone will need to exceed $9 trillion annually over the next 30 years if we are to prevent global warming from causing massive and irreversible damage to the planet’s ecosystem. To put these numbers into perspective, the required yearly investment dwarfs the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of nearly every country in the world, including economic powerhouses like Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

Understandably, the world is turning to financial markets to help stave off worst-case climate scenarios. Major institutional investors have rallied under the banner of Climate Action 100+ to foster better corporate governance related to climate change. Bill McKibben’s divestment movement urges investors to drop fossil fuel holdings from their portfolios. The multi-national Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, meanwhile, advocates for more effective climate-related disclosures to promote more informed investment, credit, and underwriting decisions. To date, however, none of these initiatives has managed to sour the love affair between financial markets and fossil fuels. A 2020 report by the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission warned that, without a meaningful price on carbon, “financial markets will operate sub-optimally, and capital will continue to flow in the wrong direction, rather than toward accelerating the transition to a net-zero emissions economy.” Sure enough, the stocks of oil-and-gas majors Exxon Mobil and Chevron are up 25 percent and 35 percent, respectively, year-to-date.

Last week, the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) released its long-awaited proposed rule for “The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors.” The commission emphasizes that the rule’s objective is not to address climate-related issues on a broad scale but, rather, “to protect investors, maintain fair, orderly and efficient markets, and promote capital formation.” There is no denying that information is power, and more climate-related information is better. But how much do retail investors, who hold stocks and other securities for their personal account, actually consult SEC disclosures? When was the last time you pulled up a company’s SEC filings before buying its stock? Survey data indicates that retail investors rely on their chosen financial intermediaries, family members or friends, as well as the business and financial press for transaction-relevant information, not regulatory filings. So how can we ensure that climate-related information finds its way into the decision-making process of retail investors?

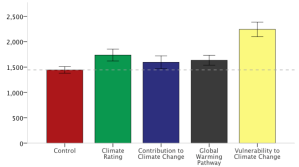

In a forthcoming article, we explore how a relatively innocuous nudge can help translate climate disclosure into investor action. We conducted a series of survey experiments, with over 1500 participants, to test and demonstrate the capacity of corporate climate ratings to promote low-carbon investment. We find that inclusion of climate ratings among the performance metrics commonly considered by investors significantly increases investment in the stock of companies with favorable climate ratings, even when other, competing stocks boast a stronger return profile. Consistent with insights from behavioral economics and behavioral finance, framing and format of ratings matter. For example, investors seem to care little about a company’s past contributions to global warming, refuting narratives of vindictiveness. Similarly, situating a company’s climate risk and governance along a global warming pathway, as championed by CDP, proved only marginally statistically significant. But the inclusion of a generically labeled climate rating boosted investment in the more climate-friendly stock by over 20 percent compared with the control scenario. The effect was even stronger for ratings of corporate vulnerability to climate change, channeling over 50 percent of additional investment toward the most climate-resilient stock. For both ratings, the effect is statistically significant and holds after controlling for investor characteristics, such as age, education, income, political views, financial literacy, etc.

Our findings are noteworthy for a variety of reasons. First, they confirm the SEC’s intuition that investors have a keen interest in, and sensitivity to, climate-related information. Second, our sample indicates that climate-conscious investment is no longer the privilege of affluent idealists who can afford to do right by the environment, even if it costs them part of their wealth. Given the opportunity, a significant number of participants in our studies prioritized climate concerns in their investment choices, knowing full well that a portion of their remuneration depended on the simulated performance of their stock portfolio. Third, and perhaps most important, the kinds of climate ratings we study are available now, without the need for regulatory intervention. A range of companies, from rating agencies like Moody’s, Fitch, and MSCI to non-profits like CDP are hard at work collecting data related to corporate governance along environmental and climate metrics. Translating these metrics, whether procured through private intermediaries or culling from SEC filings, into readily digestible information requires no regulatory imprimatur.

Online trading platforms like e-Trade, Charles Schwab, or RobinHood could easily add climate ratings to the stock performance metrics they display to investors. Similarly, climate-conscious employers could incorporate climate ratings into the menu of investment options offered to their employees as part of a 401(k) or other retirement savings plans. Managing the trillions of dollars in these plans is big business for Vanguard, Fidelity, and other providers, who hope to not only earn management fees but also promote their own fund products. Accordingly, employers command considerable clout when it comes to the structure, and display, of their employees’ retirement savings options. From Amazon to Verizon, from BestBuy to Microsoft, a burgeoning list of U.S. companies have pledged to reduce their carbon footprint to net-zero by 2040. Just imagine the possibilities if these companies insisted on including climate ratings in their employees’ retirement savings menu.

This post comes to us from professors Felix Mormann at Texas A&M University School of Law and Milica Mormann at Southern Methodist University’s Cox School of Business. It is based on their article, “The Case for Corporate Climate Ratings: Nudging Financial Markets,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog