Since the creation of the poison pill in the 1980s as a response to hostile takeovers, the corporate world has seen the rise of stakeholder governance, ESG, and stockholder activism and a host of other dramatic developments. The stock market decline following the outbreak of COVID-19 prompted a resurgence of pills, and with the recent Williams decision, the structure and strength of pills have changed in meaningful ways. In a new paper, we examine modern poison pills and propose some new ground rules for pills. These rules, we believe, would effectively balance, on the one hand, a board’s interest in considering a broad set of constituencies and the challenges of increasingly sophisticated and coordinated shareholder activists against, on the other hand, the rights of all shareholders, including activists, to solicit support for their ideas or attempt to gain control of the company.

Pill Trigger Thresholds Should Be Assessed Against Market Capitalization

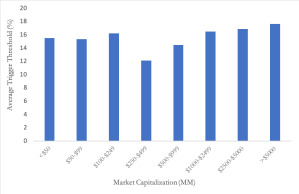

The ownership threshold for triggering a pill is typically 10-15 percent of a company’s stock for non-passive investors, no matter the size of the company. Exhibit 1 details the trigger thresholds for U.S. and Canadian pills as provided by the RiskMetrics database as of February 2022.

Exhibit 1: Trigger Thresholds for U.S. and Canadian Pills

(excludes NOL pills)

The absence of an inverse correlation between market capitalization and trigger threshold is peculiar; in today’s world, what is relevant is the dollar stake an activist can acquire, not the threshold percentage. For small-market capitalization companies, there generally must be a higher percentage equity stake to make a proxy contest worthwhile because, as a proportion of the value of the company, the costs of a challenge tend to be higher for small companies than for large ones. To make these costs worthwhile, activists must have greater proportionate gains, and to convince other stockholders that increased company value is the source of the gains, an activist must have a higher economic stake in the company. Thus, a 5 percent threshold in a large company (e.g., $30 billion market capitalization) is probably more attractive to an activist than a 10 percent threshold at a smaller company (e.g., $5 billion market capitalization).

While pill doctrine does not yet account for variations in company size (i.e., market capitalization), differing thresholds based on overall value have already been applied to deal protection. When it comes to termination (or “break-up”) fees payable by the target company if a merger agreement is terminated under specified circumstances, Delaware courts have made clear that there is no bright line rule or fixed percentage; rather, Delaware courts consider the size of the deal in determining the reasonable magnitude of the termination fee. Thus, a 6 percent termination fee in a $50 million deal may be permissible, but a 6 percent fee in a $5 billion deal may not.

It would seem logical to apply the same principle in deal protection doctrine to pill trigger thresholds. Such an approach would also represent good policy, particularly given the 10-day window for stockholders to file their Schedule 13D with the Securities and Exchange Commission, which allows stockholders to amass significant stakes before the company can adopt a poison pill.

Acting in Concert Provisions Should Prohibit Parallel Conduct

Even the earliest pills, including the Household International pill that was litigated in Moran, had an acting in concert (AIC) concept. This AIC concept was necessary because, without aggregation of affiliated entities, it would be exceedingly easy for an acquirer to, for example, acquire 3 percent through each of 10 affiliates without triggering the pill. Early pills used language tied to the definitions of a “group,” “affiliate,” and “associate” under Section 13D and Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act. Later pills, which we call second-generation, broadened the concept but still required an “agreement, arrangement, or understanding.”

However, by requiring express agreement, these first and second-generation pills did not capture implicit agreements. Savvy activists, fully aware of the “express agreement” language, collaborated with other investors through informal arrangements (or “wolf pack” activity) rather than explicit agreements, thereby not triggering these pills. Third-generation AIC provisions filled this gap by capturing shareholders “acting in concert” even without an express agreement. Instead, what is required is “parallel conduct.” The standard formulation further requires that “each Person is conscious of the other Person’s conduct and this awareness is an element in their respective decision-making processes” and that “at least one additional factor supports a determination by the Board that such Persons intended to act in concert or parallel.”

Methodology

Using Risk Metrics, we constructed a new database of 76 U.S. pills in effect as of February 2022, along with their AIC provisions.

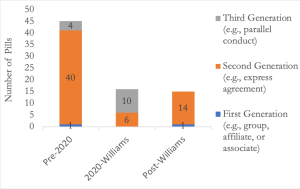

Structure and Development of AICs

Across the sample, 45 of these AIC provisions were adopted before 2020; the remaining 31 were adopted in 2020 and later, mostly in the immediate aftermath of the stock market decline caused by the global outbreak of COVID-19 in March 2020. And the majority (71 percent) of the third-generation pills were adopted in 2020 or later. All but one of these pills had a “parallel conduct + guardrails” structure, i.e., with a board determination of an additional factor indicating “that such Persons intended to act in concert or parallel.” Exhibit 2 illustrates the prevalence of certain AIC structures in the Sample.

Exhibit 2: Acting-in-Concert Structure

(excludes NOL pills)

In the years leading up to the recent case, Williams Companies Stockholder Litigation, where the plaintiffs successfully challenged an anti-activist pill adopted by The Williams Companies, Inc. at the outset of the pandemic, practitioners were including third-generation pills with greater frequency. Prior to Williams (n=61), 23 percent of pills included a third-generation parallel conduct structure. In the four years preceding Williams (n=33), the proportion of pills with a parallel conduct provision rose to 42 percent. And in the year prior to Williams, nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of the pills included a parallel conduct AIC provision. All of the third-generation parallel conduct pills (n=14) were adopted in the four years prior to Williams.

However, practitioners quickly reversed course following Williams. None of the 15 pills post-Williams contains a parallel conduct structure. Instead, these pills use first and second-generation structures. Given the timing of this reversal in relation to the timing of the Court of Chancery’s decision in Williams, the reversal is likely a reaction – perhaps an overreaction – to Williams. In Williams, the plaintiffs successfully challenged a pill that contained “a more extreme combination of features than any pill previously evaluated by [the Delaware Court of Chancery].” The Williams court did not single out third-generation, parallel conduct provisions as the source of its decision, instead discussing the combination of “a 5% trigger threshold, an expansive definition of ‘acting in concert,’ and a narrow definition of ‘passive investor’.” Nevertheless, in the wake of Williams, practitioners have taken a cautious approach and avoided parallel conduct structures entirely despite the uncertainty of whether parallel conduct provisions alone would warrant the holding in Williams. It remains unclear whether this wholesale departure from third-generation pills in the wake of Williams can be justified as an appropriate reaction to the holding of the case alone.

Implications

In our opinion, these third-generation parallel-conduct AIC provisions, along with the protection of a board-determination guardrail, represent an appropriate response to increasingly sophisticated activist attacks. And the fact that instances of the “parallel conduct + guardrails” structure for third-generation AIC provisions was significantly increasing is at least suggestive that practitioners were trending towards considering the third generation structure to be best practice. If AIC provisions can only capture express agreements, activists will simply evade the “express agreement” AIC provisions through parallel conduct or wolf pack activity. This would create a barn-door size loophole for poison pills.

Once the AIC provision is no longer tethered to an express agreement, concern arises, of course, over a board’s judgment calls about whether shareholders “intended to act in concert or parallel.” These judgment calls introduce ambiguity, and critics of third-generation AIC provisions might argue that the ambiguity will have a chilling effect on socially desirable conversations among shareholders about the company. In response to these valid criticisms, we would suggest that the guardrail of a board determination is not a trivial thing. In general, no board wants to trigger a pill – it can wreak havoc on the company’s balance sheet – and it represents a significant board decision to deliberately dilute a shareholder. And all of these board determinations are of course subject to the board’s fiduciary duties to all shareholders.

This post comes to us from Caley Petrucci, a Climenko Fellow and lecturer on law at Harvard Law School, and Guhan Subramanian, the Joseph Flom Professor of Law & Business at Harvard Law School and Douglas Weaver Professor of Business Law at Harvard Business School. It is based on their new article, “Pills in a World of Activism and ESG,” forthcoming in the University of Chicago Business Law Review and available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog