On July 19, 2022, in the Twitter v. Musk litigation, Chancellor Kathaleen McCormick presided over what was likely the most widely observed hearing on a motion to expedite in the Delaware Court of Chancery’s history. While deal bust-ups are front page fare for the financial press, the high profile of this case brought the Court of Chancery further into the national consciousness than usual (though who among us hasn’t asked “what is a chancery?”). On the day of the hearing, the public access telephone line was, indeed, “lit,” hitting its maximum capacity with merger arbs (and other interested parties) hanging on every word. But in the end, the chancellor did something rather routine in Delaware these days: She expedited the litigation. Trial was set for October.

How can the Court of Chancery move so quickly in such a complex situation?

To the uninitiated, it may seem “insane to do a trial like this in 60 days,” but the Court of Chancery regularly handles highly complex litigation on tight schedules. It’s a rocket docket in a way, but the court does not simply pump out cursory or standardized decisions as if on an assembly line. Rather, its opinions are detailed, often finely crafted, and customized to the specifics of the litigation and the precedential landscape. Read one of Chancery’s 250-page opinionsand you’ll get the idea. This only deepens the puzzle: How can Chancery learn fast enough to handle novel situations so quickly?

One factor is, of course, the high quality of its judges. And Chancery is a specialized court in many respects, focusing extensively (though not exclusively) on matters of corporate law and governance. But plenty of organizations – think of General Motors in the second half of the 20th century – staffed with the best and brightest nevertheless stagnate. Relatedly, specialization often leads to routinization, which is often the kiss of death for vibrant innovation.[1]Something more keeps Delaware on its toes.

A hint of the answer is found in an insightful article that Bill Savitt, Twitter’s lead counsel in the controversy du jour, wrote 10 years ago. Savitt pins the “genius” of the Chancery system on a network that combines not only “expert decision makers” but also a “cadre of government-supervised enforcement attorneys.”[2] It is the expertise within Chancery’s broader ecosystem – both bench and bar – that fuels the court’s performance.

Perhaps something about the relationships among lawyers in Savitt’s “cadre” of attorneys contributes to Chancery’s ability to swiftly innovate. Building expertise in litigation is deeply social. Wise counselors earn their gray hair in the course of debating with other attorneys about legal tests, the interplay between facts in a case and a legal standard, a judge’s view of an issue, and other matters. The frequency, quality, and variety of those debates may strengthen the ability of judges and attorneys to learn.

A little social science can show us how the social structure of Chancery’s ecosystem might matter. The way information flows within a network helps (or hinders) organizations trying to achieve that tricky balance between the exploitation of established knowledge and the exploration of new possibilities upon which innovation relies. The idea is straightforward: You will struggle to innovate if you are (1) cut off from sources of new information or (2) so inundated with new information that you cannot make heads or tails of it. Innovation thrives in the goldilocks zone between those two extremes.

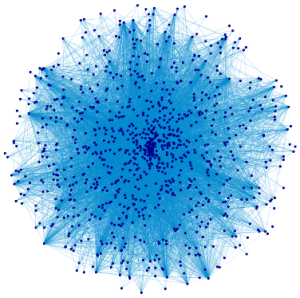

So, let’s look at the social structure of Chancery’s ecosystem. Below is a network graph derived from a dataset of judges and litigators involved in Court of Chancery cases from January 1, 2004, until December 31, 2020.[3] That time-period incorporates 15,077 unique civil actions involving 4,420 individual attorneys and jurists. Those individuals are the “nodes” in the network, and “links” are formed between those nodes when individuals work on a case together (in that respect, a link represents the information that flows among the counsel and the judge in a given case). Nodes and links are then aggregated over time. For instance, the graph below depicts all individuals and the links between them for the first year in the dataset, 2004.

Figure 1: Chancery Litigation Network, 2004

We can learn a few things from the network in Figure 1. First, the network is a single component with little clustering within it— e.g., we do not see discrete sub-communities in the network. Second, the network has a core of highly connected nodes – the judges and most influential attorneys that work on a large number of matters and therefore have the most connections.[4] Third, there are a significant number of connections between the nodes in the core and the periphery of the network – in other words, highly connected nodes do not tend to link only with other central nodes but, rather, have a material number of connections with less experienced lawyers.

What might that mean? Those characteristics suggest an environment where judges and attorneys are exposed to a large amount of highly diverse information. One isn’t just litigating with the same handful of people over and over again. Rather, one works with a range of lawyers, some based in Delaware and some from other jurisdictions, some with deep experience in Chancery and some with little. Due to that variety, one may be introduced to different perspectives, particularly on emerging issues without clear answers.

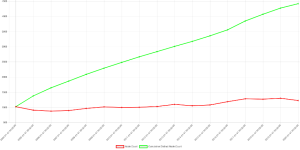

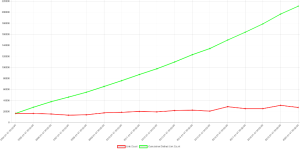

That diversity of connections compounds over time. Figures 2 and 3 below depict, respectively, the number of new nodes and links in the network from year to year. The red line depicts the node/link count for each year, while the green line gives the cumulative count of distinct nodes as time progresses. Roughly, 50 percent of the nodes and links in the network are new each year. That’s quite a bit of change.

Figure 2: Year by Year Network Comparison, Change in Nodes

Figure 3: Year by Year Network Comparison, Change in Links

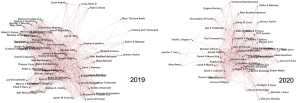

We can also drill down into an individual attorney’s direct network and see what that diversity means on a personal level. Figure 4 below compares the direct connections of one of Twitter’s Delaware counsel, Ed Micheletti of Skadden Arps, between the years 2019 and 2020. As the figure suggests, the personal network of a given attorney changes materially from year to year.

Figure 4: Change in a Single Litigator’s Direct Network from 2019 to 2020

This analysis, which is admittedly cursory, raises the possibility that the social structure of Chancery’s ecosystem unsettles expectations and requires attorneys to interrogate their positions by exposing them to diverse viewpoints. Put another way, the mental friction from working with a stranger who thinks differently may at first be uncomfortable, but it can ultimately strengthen lawyers’ and judges’ ability to learn. Four potential lessons emerge from the discussion above.

First, if an institution like Chancery relies on its network of expert professionals, as Savitt argues, then it is worth directing academic and policy attention toward understanding and developing these networks. We have studied innovative ecosystems like Silicon Valley‘s relentlessly for decades but largely ignored how they work in legal settings, even though those systems create the fundamental infrastructure for modern markets.

Second, by shining a light on the learning system we see in Chancery, we can see whether it exists elsewhere. If not, why not, and what should be done about it?

Third, the political left and right are pushing for change in how capitalism operates, from conservatives’ new appetite for industrial policy to progressives’ calls for worker representation on corporate boards. Understanding how our law evolves as a system sheds light on how its structure might constrain the reforms that are being proposed.

Fourth, illuminating a social structure allows us to see who is excluded from it. The data above can show us, for instance, the extent to which women and attorneys of color are represented in an important part of our legal system. We can get a better sense of who has influence in an ecosystem like Chancery’s based on their position in the network.

ENDNOTES

[1] For a thoughtful treatment of the challenges of maintaining innovation, see Josh Whitford, The New Old Economy: Networks, Institutions, and the Organizational Transformation of American Manufacturing (2005).

[2] William Savitt, The Genius of the Modern Chancery System, 2012 Colum. Bus. L . Rev. 570, 586 (emphasis added).

[3] All data was collected from the Court of Chancery’s publicly available docket information. The network extracted from that data includes both members of the Delaware bar and lawyers from other jurisdictions appearing pro hac vice in Chancery matters.

[4] In this network, a node’s number of links will also be a function of the size of the teams in a given litigation.

This post comes to us from Professor Matthew Jennejohn at BYU Law School.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog