Our paper utilizes National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) coaching contracts as a managerial setting to examine whether higher top-managerial pay (our Gridiron CEOs) is associated with better team performance. Coaching contracts are quite compelling as they are available for nearly all public universities. Such contracts are for fixed terms: five years on average, with some as long as ten years. In contrast, CEO contracts are mostly “at-will,” meaning they can be terminated without liability, while the rest are for terms of from two to five years.

Dave Clawson, the head coach at Wake Forest University, posted 3-9 records in each of his first two years on the job (2014 and 2015). In 2016, the football team won seven games, and in 2021, it won 11, earning Clawson multiple long-term extensions to his contract. Wake Forest and its stakeholders appear to have given Clawson time to develop a strong team, and Clawson was rewarded. Was Clawson focused on maximizing his compensation during those early years, or was his outlook longer-term?

FBS coaches regularly earn five to 10 times the salary of university presidents. However, the university may not itself fund much of the salary. Instead, coaching contracts commonly distinguish between base and supplemental compensation. While a university may nominally pay a coach’s entire compensation package, the vast majority of a coach’s supplemental compensation is granted in exchange for activities required to satisfy the university’s media and apparel sponsorship deals. This supplemental compensation is often funded through these media and sponsorship contracts.

Most CEO studies assume compensation is negotiated annually. In practice, details are negotiated at the time of the initial contract signing. While CEOs are in fact paid annually, their compensation structure (but not amount) will have already been previously determined. Rational managers would therefore maximize utility by optimizing their total payout (i.e., the sum of guaranteed and performance compensation) over the entire contract. In other words, it may be more advantageous for managers to chase one large annual performance-based payout rather than a series of smaller guaranteed ones.

Instead of using the common annual approach, our novel empirical design calculates compensation as an equivalent annual annuity occurring over a contract’s term. In effect, we are positing that managers view their compensation as the discounted present value of future expected payoffs over the life of a contract. By utilizing the full value of expected payouts over a contract’s life, we allow for well-documented occurrences of managerial gaming such as earnings management, where performance indicators are manipulated to reach a specific year’s benchmark at the expense of current or future firm value. Additionally, we observe exact values for both performance and guaranteed components of coaching pay, allowing us to distinctly address performance bonuses, which only pay off in a minority of instances. Under pay-by-year empirical designs, guaranteed pay components would be overvalued.

The NCAA also has impeccable performance data. Performance is readily explained through a variety of explicit factors, including win/loss records, bowl wins, recruiting success, and revenue generation. We track individual coaches’ performance, relative to their prior coaching position, across the majority of their career. We also test the relation between performance and a wide array of individual coaches’ characteristics such as age, university tenure, and prior NFL experience. Such measures are all readily available by season across various public sources, and due to the purely competitive nature of sports, these are all relative measures. This ensures relative performance evaluation is endogenous, and exogenous market factors are extraneous.

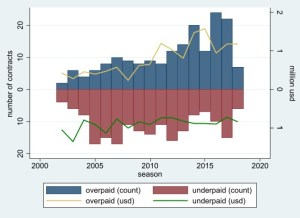

The primary goal of our research is to determine whether higher coaching pay leads to improved team performance. This prompts us to use a two-stage design. The first stage explores what pay level a coach should expect at the time of negotiation. First, we find more coaches are underpaid than overpaid within our sample. However, both the number of overpaid contracts and the amount by which contracts are overpaid have increased over time. On the other hand, underpaid contract trends have remained stable. We include Figure 2 from our paper to demonstrate these findings. Following from this analysis, our first question is whether previous performance affects future pay. We find not only that it does, but that universities take into account a coach’s entire career history during negotiation. Interestingly, the residuals from our model also inform us as to whether a coach has been overpaid or underpaid.

Figure 2 from Gridiron CEOs: Revising the Executive Excess Pay-Future Performance Nexus

The second stage of our analysis answers the simple question of whether future performance can be bought. Using the first stage residuals, we show that overpaid coaches do not generate better performance. Further, the most overpaid coaches do not live up to their maximum compensation packages. On the other hand, guaranteed compensation has no significant positive or negative effect on future performance. In effect, not only are schools unable to buy wins, but they may also end up overpaying in the pursuit.

Our findings generally concur with conclusions found in the excess compensation literature while being contrary to the sports research. Future empirical investigations of principal-agent theories would benefit from incorporating multi-period dynamics. Annual compensation approaches ensure a large number of manager-year observations but do not accurately describe the multi-year design of contracts and compensation optimization.

The landscape for collegiate sports is rapidly changing. In April 2021, the NCAA approved a one-time transfer for all collegiate athletes without the need to sit out a year (Auerbach, 2021). In June 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously against the NCAA in NCAA v Alston, which pronounced that the NCAA could not limit education-related benefits to student-athletes. Quickly following that June ruling, the NCAA (in July 2021), allowed student-athletes to sell their “Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) (Auerbach and Vannini, 2021). While the NCAA has repeatedly affirmed that NIL cannot be used for “pay-to-play,” numerous accusations have swirled in the press about such pay occurring. Many have worried about the connection between NIL opportunities and recruiting, both from high schools and of transfers from other colleges. Another topic that has garnered attention recently is the renegotiation of conference media contracts. For example, the Big 10 just negotiated a new media contract that will generate more than $7 billion in total, which will result in a distribution of anywhere between $80 and $100 million per year to each school in the conference (Rittenberg, 2022). Such developments could substantially change how and how much coaches are paid, while portending changes in the corporate managerial world.

REFERENCES

Auerbach, N. and Vannini, C. (2021, July 1). NCAA approves interim NIL policy for college athletes. https://theathletic.com/news/ncaa-approves-interim-nil-policy-for-college-athletes/HSSJIy9wkRMg/

Rittenberg, A. (2022, August 18). Big ten completes 7-year, $7 Billion media rights agreement with Fox, CBS, NBC. ESPN. https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/34417911/big-ten-completes-7-year-7-billion-media-rights-agreement-fox-cbs-nbc

Auerbach, N. (2021, April 15). NCAA approves one-time transfer rule, end of recruiting dead period. The Athletic. https://theathletic.com/news/ncaa-approves-one-time-transfer-rule-end-of-recruiting-dead-period/z4VeShqu36oD/

This post comes to us from Yuri Hupka at Oklahoma State University – Stillwater, Jacqueline L. Garner at Georgia Institute of Technology’s Scheller College of Business, Betty J. Simkins at Oklahoma State University – Stillwater, and Phillip Humphrey at Brigham Young University, Idaho. It is based on their recent paper, “Gridiron CEOs: Revising the Executive Excess Pay-Future Performance Nexus,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog