Crypto is at a crossroads. After a cascade of bankruptcies – including FTX’s implosion – millions of defrauded customers, and trillions of dollars in value destruction, many are wondering whether the sector has a future. Amidst the wreckage, after years of deference to the industry, regulators are taking off the gloves, “carpet bombing” crypto with enforcement actions, including recent cases against two leading players. The stakes could not be higher. Yet, consensus remains limited on seemingly basic questions like, what is crypto?

In a new article, I posit that a threshold challenge for crypto regulation concerns definitions and taxonomy. Rather than a uniform asset class, crypto is a highly heterogeneous universe of over 10,000-instruments with distinctive features and economic characteristics.

The article’s essential contribution to the literature is a unifying framework that separates crypto into categories based on the economic substance and legal attributes of particular assets – providing a powerful tool for understanding market structure, revealing abusive industry practices, and identifying areas for regulatory action.

In particular, the article shines a light on crypto’s murkiest corner: so-called “utility tokens,” finding a stark mismatch between regulatory guidance and market practice around these instruments, which the article posits to be most economically analogous to loyalty programs, such as airline miles. The mismatch harms all stakeholders – opening investors to exploitation, ensuring poor governance, and facilitating accounting shenanigans. Fortunately, the biggest problems with this status quo can be alleviated through regulatory enforcement of asset-level crypto delineations, an emphasis on consumer protection, and the closing of accounting loopholes to ensure financial stability and appropriate incentives.

A Unified Crypto Taxonomy

“Cryptocurrency” is commonly defined as “a form of digital money secured not through the backing of a state or financial institution, but through cryptography.” Though most crypto assets[1] are distinct from “currency” as the term is properly understood, the idea of “money” without government is not new; Before the Civil War, for instance, the U.S. had over 8,000 different kinds of “money,” typically issued by individual banks. Yet, crypto is distinctive because it depends solely on technology rather than on governments (as U.S. dollars do) or financial institutions (as pre-Civil War currency did) and due to the ferocity of its global ascent, from a single asset (Bitcoin) to 10,000-plus instruments, once valued at over $3 trillion.

While often referred to as a single asset class, in reality the crypto sector exhibits significant heterogeneity, with instrument-level economics and features that don’t quite fit dimensions of traditional asset classes and existing regulatory frameworks. These points of incongruence are a threshold hurdle for understanding and overseeing this evolving ecosystem – exacerbating uncertainty for regulators, market participants, and the industry itself.

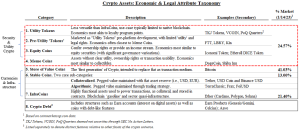

The article proposes a unifying framework that divides the sector into two groups: (i) Security and Utility Crypto, the focus of the article and (ii) Currencies and Infrastructure, which are further sub-divided into eight categories, as shown in the diagram below:[2]

The “Security and Utility Crypto” grouping comprises 24.6 percent of sector value but over 9,000 unique instruments. Despite logical economic demarcations, industry practices – including intentional misrepresentations – blur the distinctions among them, complicating market and regulatory treatment. A critical focus of the article is using its framework to untangle the legal, regulatory, and economic demarcations between these assets – a strong majority of which likely constitute unregistered securities.

Mapping the Framework to Regulatory Structure

The classification challenges surrounding crypto are made more difficult by America’s “highly fragmented” system of financial regulation, and further exacerbated by intense industry lobbying – much of it led by FTX – as well as market practices often at odds with legal guidance.

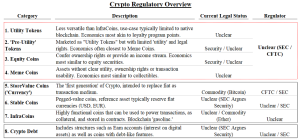

As a result, nearly 15 years after crypto’s advent, the sector lacks not only clear guiding principles, but also unambiguous answers to seemingly straightforward questions – including the legal status of crypto assets and the relevant regulatory jurisdiction, particularly for the ‘Security and Utility Token’ category, as detailed in the table below.

These challenges are most obvious in what may be crypto’s murkiest corner: so-called “utility tokens,” an industry-created construct to arbitrage around SEC jurisdiction – now at the heart of the sector’s predicaments.

Despite a general view that most crypto constitutes securities, the SEC has permitted unregistered crypto offerings subject to specific safeguards, detailed in a series of no-action letters. As a legal, economic, and practical matter, the assets envisioned by the no action letters – reflecting “true” utility tokens – most closely resemble a familiar construct: miles and points associated with loyalty programs.

However, a central incongruence underlying crypto markets is the clear mismatch between the SEC’s conception of utility tokens and the crypto sector’s application of the term: the “Pre-Utility Token Problem,” as the article terms it. “Pre-Utility Tokens” are crypto assets: (i) labeled as “utility tokens,” (ii) marketed like stocks, but (iii) offering minimal legal rights – most akin to digital trinkets. The problem is far more than semantic; Pre-Utility Tokens represent the majority of the crypto market by issuance.

The Pre-Utility Token Problem and Its Implications

The prevalence of Pre-Utility Tokens creates a multi-layered classification incongruence that harms all stakeholders – including crypto purchasers, legitimate projects, and the broader ecosystem – while fostering regulatory uncertainties.

One of the most consequential policy issues associated with Pre-Utility Tokens is issuers’ reliance on glitzy but misleading marketing to essentially con retail investors into buying tokens with early-stage equity risk, but without legal protections or financial benefits. Crypto companies have powerful incentives to blur the lines between assets and to mislead investors: Selling mis-labeled tokens as equity is equivalent to token buyers “giving the issuers free money,” as one analyst put it. This dynamic also fosters governance challenges, as crypto shareholders – company management and institutional investors – have interests distinct from those of token-holders, representing a conflict little understood in the market and unexplored in the literature.

The structural, governance, and disclosure issues underlying Pre-Utility Tokens create a value-destructive façade with misaligned incentives. A critical financial and accounting mismatch underlies crypto projects: They treat self-issued utility tokens as assets rather than the liabilities they clearly represent, resulting in misguided goals of pumping up token prices instead of building real businesses. It would be as if American Airlines treated its own miles – obligations for future performance – as its primary asset and worked to hype their value without bothering to fly another plane.

Rationalizing Crypto Regulation and Market Practice

While some prominent commentators have argued against “legitimacy-inferring” crypto regulation in favor of letting the sector “burn” – and others have suggested outlawing crypto outright – in reality, as the IMF persuasively articulated, “[d]oing nothing is untenable as crypto assets may continue to evolve despite the current downturn.”

At the same time, some broadly uncontroversial measures can alleviate many of the sector’s most acute challenges. First, regulators must require issuers to follow existing provisions on asset classification with a default towards more stringent regulatory requirements while emphasizing long-neglected consumer protection – potentially through a greater role for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Second, the accounting mismatch for company-issued utility tokens must be remedied by treating tokens like miles – as liabilities, rather than assets. Finally, the article cautions against reducing regulatory standards for Pre-Utility Tokens, finding arguments for doing so unpersuasive – and the risks significant.

ENDNOTES

[1] Given the relatively fluid and evolving taxonomy, the Article uses the term ‘crypto’ quite broadly, often in reference to the sector as a whole, with “crypto assets” corresponding to a similarly broad grouping of associated financial assets. Please see Parts II and III of the Article for additional taxonomical context and detail.

[2] Crypto Debt reflects a potential third grouping beyond the scope of this analysis due to uniquely complex and evolving issues, but mentioned herein due to its economic significance.

This post comes to us from Lev Breydo, a visiting assistant professor at Villanova University’s Charles Widger School of Law. It is based on his recent article, “Stocks, Memes or Miles? A New Crypto Taxonomy & Regulatory Paradigm,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog