Last Thursday’s split summary-judgment decision in the case that the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) brought against Ripple Labs, Inc. (Ripple) and certain of its senior leaders is bonkers. In partly holding for the defendants, the opinion ignores well established doctrine that interprets “investment contract”[1] and is inconsistent in its treatment of ordinary investors’ expectations as distinct from the expectations of sophisticated investors. The opinion also ignores the sufficiency of services as consideration for assets otherwise bearing the characteristics of a security.

The term “investment contract” defines a subtype of “security,” i.e., the touchstone of SEC regulation. The presence of a security in the form of an investment contract or otherwise invokes the jurisdiction of the SEC and its protective regimes, which include anti-fraud authorities and requirements that public offerings of securities be registered. The registration process involves filing of disclosure documents with the SEC for its review and limitations on communications and sales. As a result, unregistered public offers and sales involving an investment contract can lead to costly violations. These were the violations at issue in the case.

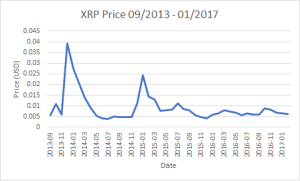

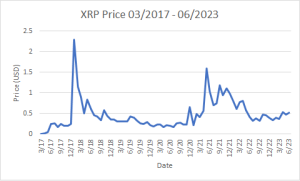

The case involves the XRP token, which was substantially developed and supported by Ripple and its executives.[2] The token can be transferred through entries recorded on an open source, decentralized, digital ledger. Like many other cryptocurrencies, this one is not redeemable for specific services such as filesharing, communication, etc., but rather seeks solely to act as a means to store and transfer value. XRP is designed for cross-border payments, and based on the decision, carries consumption value (i.e., value other than as a potentially appreciating investment). However, price data[3] from coinmarketcap.com show that XRP is too volatile to reliably serve as a store of value and is likely to be purchased primarily for speculative purposes:

The opinion identifies SEC v. W.J. Howey Co., 328 U.S. 293 (1946) as a seminal case construing “investment contract,” Quoting from Howey, the opinion interprets an investment contract as “a contract, transaction[,] or scheme whereby a person [(1)] invests his money [(2)] in a common enterprise and [(3)] is led to expect profits solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party.”[4] The court then applies these three prongs to distinct sets of offers and sales of the XRP tokens: (1) institutional sales; (2) sales of the token through exchanges where the transactions maintained counterparty anonymity; (3) use of the token to reward employees and vendors; and (4) sales of the tokens by senior leaders through the exchanges referenced in (2).

The opinion correctly views the institutional sales as involving securities, holding for the SEC. The institutional sales involved transactions with hedge funds, wealthy individuals, and other sophisticated market participants, at least some of whom were going to promptly resell the XRP tokens rather than hold them as investments. The opinion acknowledges (at page 14) a line of decisions that analyze how non-securities can be transformed into securities through marketing schemes such as promotions of silver foxes, worms, and other animals as investments.[5] The institutional sales involved years of marketing that explained how Ripple’s efforts could increase the tokens’ value, including publicly available statements via YouTube, Reddit, and other online channels. Although not referenced in the opinion, the SEC’s pleadings outlined how Ripple and individual defendants induced third parties to establish trading markets in XRP.[6] On these facts, the opinion properly held that the offers to institutional investors involved investment contracts because (1) investors made payments to Ripple in exchange for XRP tokens that the investors expected to be profitable, (2) Ripple pooled that capital and used it to finance its operations, and (3) the investors had a reasonable expectation that, to the extent the XRP tokens appreciated in value, that appreciation would be predominantly due to the efforts of Ripple.

In considering sales conducted anonymously through exchanges, however, the opinion reached positions inconsistent with the preceding analysis. Primary market sales occurred side-by-side with secondary sales on these anonymous exchanges. In other words, a purchaser of an XRP token would not know whether she was purchasing it from Ripple or another investor. The volume of secondary sales dwarfed the number of primary sales, so that the exchange transactions functioned primarily to provide liquidity in the token rather than provide Ripple with capital. From these facts, the opinion makes a bizarre leap, reasoning that because purchasers did not know whether their money was flowing to Ripple or another investor, they had a different reason for expecting their purchases to be profitable from the institutional investors:

It may certainly be the case that many Programmatic Buyers purchased XRP with an expectation of profit, but they did not derive that expectation from Ripple’s efforts (as opposed to other factors, such as general cryptocurrency market trends)—particularly because none of the Programmatic Buyers were aware that they were buying XRP from Ripple. (page 24)

The opinion does nothing to address the public statements that reached both exchange participants and institutional investors regarding Ripple’s efforts to support and develop the token, other than to claim that because purchasers on exchanges were less sophisticated than the institutional purchasers, they would not have been able to understand those public statements:

There is no evidence that a reasonable [anonymous purchaser on an exchange], who was generally less sophisticated as an investor, shared similar ‘understandings and expectations’ and could parse through the multiple documents and statements that the SEC highlights, which include statements (sometimes inconsistent) across many social media platforms and news sites from a variety of Ripple speakers (with different levels of authority) over an extended eight-year period. (page 25)

This logic deprives ordinary investors of the protection of securities laws while extending it to sophisticated investors because of the former’s asserted inability to understand how Ripple contributed to the appreciation of the XRP token. In other words, the opinion holds that while Ripple may have made public statements – unsophisticated investors weren’t clever enough to understand them and instead must have tied their expectations that the tokens would appreciate to factors unrelated to Ripple’s efforts.[7] But if it were truly market trends and other factors unrelated to Ripple’s efforts that drove the price of XRP tokens, there would be no basis for finding XRP to be a security with respect to the institutional investors.[8] In short, the opinion’s reasoning as to why exchange-mediated sales do not meet the third prong from Howey is incoherent and inconsistent with its holding with respect to institutional transactions.[9] Provided an adequate record has been established, the SEC should appeal.[10]

There are other serious errors in the opinion, including an excessively credulous view of the individual defendants’ confusion about their legal risk and mistakes as to control-person liability. However, the other critical issue for the SEC to appeal is the opinion’s disregard for cases expanding on the first Howey prong. The opinion cites Int’l Bhd. of Teamsters v. Daniel, 439 U.S. 551 (1979) for the proposition that certain forms of non-cash services compensation do not qualify as investment contracts. Daniel involved a union member’s rights under his union’s defined benefit non-contributory pension plan. The case turned on rather complex facts (as has a line of subsequent cases looking at pension plans as investment contracts). However, two key factors in Daniel were that the employee’s interest in the pension plan was not “an interest that had substantially the characteristics of a security” and that participation was an inseparable part of a compensation package (e.g., the plaintiff-employee could not negotiate for a lower retirement plan participation and higher baseline pay). In holding that the first Howey prong is not met when XRP is used to compensate service providers, the opinion relies on the following quote from Daniel:

In every case [finding an investment contract] the purchaser gave up some tangible and definable consideration in return for an interest that had substantially the characteristics of a security. (page 26)(internal quotation and citation omitted).

But Daniel makes clear it does not stand for the proposition the opinion uses it for, cautioning almost immediately:

This is not to say that a person’s ‘investment,’ in order to meet the definition of an investment contract, must take the form of cash only, rather than of goods and services.[11]

Nor does the opinion consider the material distinctions between, on the one hand, a non-transferrable interest in a pension plan that covers a broad swath of employees, and on the other hand, a transferrable token that is experiencing years of significant volatility and appreciation from speculation. The pension plan interest doesn’t have “substantially the characteristics of a security” in contrast to the XRP token. And unlike the individually negotiated grants of XRP tokens prompting the SEC’s suit, pension plan interests generally are not separable from other compensation components. As a result of narrowly reading “investment contract” in the context of service-based consideration, the opinion opens a path for service recipients to skirt hundreds of pages of SEC guidance written over decades on compensatory offerings of securities to employees and other service providers.[12]

Perhaps the most important lesson from this opinion, as from so many others, is for legal academics. I believe there is value in examining whether the law has been faithfully implemented and enforced rather than exclusively focusing research on novel normative proposals for its refinement.[13] And as teachers, it is important to prepare our students for defective but powerful decisionmakers who will have great sway in their lives and the lives of their clients.

ENDNOTES

[1] Some of the issues in the opinion may be due to SEC advocacy (or lack thereof) rather than other factors.

[2] From one perspective, the case challenges the conditions under which an asset or a scheme involving an asset may be taken outside of the SEC’s purview when its value is tied to a group effort rather than the effort of a single issuer, but that is not the focus of the opinion’s reasoning or this post. There are interesting and potentially important distinctions between those developing and implementing XRP software, on the one hand, and Ripple and its executives, on the other hand – but the lack of overlap between these two groups is not meaningfully explored in the opinion.

[3] The two graphs present opening prices over two periods, which are split because the higher prices in the later period would not allow perceptible depiction of the volatility in the earlier period if one trend line was used.

[4] This quote is copied without alteration from page 11 of the opinion and, as the opinion to some extent acknowledges, no longer reflects governing law. For example, more than “money” is recognized under the first prong, and profits do not have to derive “solely” from the efforts of a promoter or third party under the third prong. All citations in this post to page numbers refer to pages in the opinion unless specified otherwise.

[5] A more important if less colorful case in this progeny involves a Merrill Lynch program that offered support (including secondary market liquidity) for certificates of deposit, converting them into securities within the context of this financial scheme. Gary Plastic Packaging Corp. v. Merrill Lynch, 756 F.2d 230 (2nd Cir. 1985).

[6] Concerningly, the recitation of facts in the district court’s opinion – while by no means sufficient to legally justify its conclusions – omits and implicitly rejects important factual assertions the SEC made in pleadings prematurely at the summary judgment stage.

[7] Although the opinion does not raise the following potential basis for its holding expressly, it is alluded to and should be addressed. Particularly in the securities context where sophisticated investors receive fewer mandatory protections, it is inappropriate at the summary judgment stage to hold that sophisticated investors were mistaken as to their views for why XRP would appreciate in value (but protected in their reliance on a mistaken view) while unsophisticated investors accurately concluded that the value of XRP tokens was not predominantly tied to Ripple’s efforts. While the marketing context affects “investment contract” status, here both constituencies received similar and in many cases the same communications from Ripple and its executives.

[8] The opinion also asserts that anonymous purchasers of XRP tokens on exchanges “were entirely unaware of Ripple’s existence.” (page 24). Even if this assertion is true with respect to typical market participants, which I doubt, it is irrelevant at summary judgment. Some of the thousands of purchasers were aware of Ripple and its importance to the XRP token and their presence would be sufficient to taint the offering – and their absence should not be established by judicial fact-finding at the summary judgment stage.

[9] Another argument that the opinion does not examine and is not appropriately resolved at the summary judgment stage is worth reflecting on. Some of the XRP token purchasers active on exchanges likely were using the tokens for effectuating cross-border and other payments, and to do so, they may have been purchasing tokens and promptly transferring them (or receiving tokens and promptly selling them). These users would not have been exposed to the volatility and appreciation (and would not expect a profit from holding the tokens). However, tokens were inventoried by other market participants to enable these momentary users. It is the expectations of these holders of inventory that are relevant, and we do not know to what extent the inventories were held to make fees from selling the tokens to users as opposed to make money from the tokens’ appreciation.

[10] See n. 1, supra.

[11] Daniel at n. 12 (emphasis added). See Dubin v. E.F. Hutton Grp., Inc., 695 F.Supp. 138 (S.D.N.Y. 1988)(treating employee interest in an equity plan as a security).

[12] See Form S-8 (for public companies) and Rule 701 (for private companies).

[13] Scholarship on judicial non-compliance is growing. See, e.g., M. Todd Henderson & William H. J. Hubbard, Judicial Noncompliance with Mandatory Procedural Rules Under the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act, 44 J. Legal Stud. S87 (2015); Matthew Tokson, Judicial Resistance and Legal Change, 82 U. Chi. L. Rev. 901 (2015); Diego A. Zambrano, Judicial Mistakes in Discovery, 113 Nw. U. L. Rev. 197 (2018).

This post comes to us from Professor Ilya Beylin at Seton Hall University Law School. Prof. Beylin acknowledges with gratitude the lightning-fast feedback he received on this piece from colleagues and friends.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog

Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts. Do you see anything wrong with the judge’s exclusive focus on the purported subjective beliefs of the retail purchasers as compared to Ripple’s actual involvement in supporting XRP?