Existing securities laws primarily target lies. However, financial influencers, or finfluencers – people or entities with outsized influence on investor decisions through social media – need not lie in order to influence their followers. This means that finfluencers can profit off of their followers’ trading activity while steering clear of the securities laws.

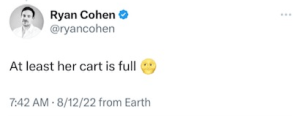

In a new paper, I argue that a recent district court ruling narrows finfluencers’ ability to do so. On July 27, 2023, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in In re Bed Bath and Beyond that certain securities fraud claims could proceed against the activist investor and finfluencer Ryan Cohen.[1] Most notably, the court denied (in part) Cohen’s motion to dismiss claims that he had engaged in a pump and dump scheme in Bed Bath and Beyond’s securities. Specifically, the court ruled that the following tweet from Cohen could be reasonably interpreted as material and misleading:

Cohen tweeted the above in response to a CNBC story that stated Bed Bath and Beyond faced grim financial prospects and included a picture of a woman with a shopping cart at the store. To be sure, this ruling arose in the context of a motion to dismiss and simply concluded that plaintiffs’ claims were plausible. Nevertheless, it also reflects growing concerns about the reach of finfluencers and their potential for committing fraud and manipulation.

Finfluencers like Ryan Cohen increasingly drive investing and trading trends in a wide range of asset markets, from stocks to cryptocurrency. They do so by providing powerful coordination mechanisms across diffuse investor and trader populations. Moreover, finfluencers’ social media activity generates stock price movements through followers’ trading activity even when a finfluencer has not made any statements containing information directly related to stock price or the underlying issuer’s prospects. For example, Cohen’s 13D filing with the SEC simply reiterated his existing holdings in Bed Bath and Beyond, yet it led to a 70 percent increase in the price of its stock as a result of his followers’ trading,[2] and a tweet of a picture of himself with chopsticks up his nose sparked rampant discussion among his followers that the picture previewed an upcoming GameStop stock split (Cohen is the chair of GameStop’s board).[3]

These actions are not obviously illegal. Stock prices reacted, but no clearly false information was disseminated. Nor, arguably, was any new information. This has highlighted a gray area in the securities laws: A finfluencer’s statements may not be factually untrue or clearly deceptive, but they can be interpreted as misleading depending on the context and the particular beliefs held by the finfluencer’s social media followers. Moreover, such statements can harm investors who buy or sell based on their interpretation of the finfluencer’s activity. In re Bed Bath and Beyond opens a path for seeking redress in this gray area. It does so by considering materiality from the perspective of the reasonable retail investor.

An actionable statement is one containing a material fact or omitting a material fact needed to make the statement not misleading. Materiality is judged from the viewpoint of a reasonable investor considering the total mix of information. While the figure of the reasonable investor has eluded clear judicial or regulatory definition, existing guidance does gesture to a reasonable rational investor, one who is relatively financially sophisticated, understands market concepts, and conducts financial and mathematical research on her own. Many have criticized this standard as creating an aspirational figure that does not comport with reality, and certainly not with the reality of the typical retail investor.

The court in In re Bed Bath and Beyond, however, assessed materiality in today’s context of social media and finfluencing. It considered the “meme stock subculture,” which associated a moon emoji with the implication that “a stock will rise.”[4] And it considered Cohen’s particular relationship with his followers, including his identity as a powerful finfluencer. The court specifically noted that “[i]nvestors may have reasonably seen Cohen as an insider sympathetic to the little guy’s cause: He interacted with his followers on Twitter. He appeared to speak truth to power, criticizing ‘compensation for the Corporate Power Brokers,’” among other factors, “[s]o it was not crazy for retail investors to follow his lead.”[5]

This places an emphasis on retail investors’ interpretation of social media activity. Viewing materiality from the perspective of a reasonable retail investor opens a potential path forward for the millions of retail investors who have been or might be harmed by finfluencer activity that falls in the gray area of the securities laws. It also calls into question courts’ tendency to apply a standard that assumes a rational and sophisticated reasonable investor, and it draws support from jurisprudence that emphasizes the importance of context. In doing so, it narrows a gap in securities oversight, demonstrating that existing securities laws can be flexible enough to deter and punish a significant portion of problematic finfluencer behavior and provides a way for harmed retail investors to seek redress from careless finfluencers.

ENDNOTES

[1] In re Bed Bath and Beyond Corp. Sec. Litig., 2023 WL 4824734 (D.D.C. July 27, 2023). The SEC is also investigating Cohen’s sale of Bed Bath and Beyond’s stock in August 2022. See Dave Michaels and Lauren Thomas, SEC Probes Ryan Cohen’s Bed Bath & Beyond Trades, Wall St. J. (Sept. 7, 2023), https://www.wsj.com/business/retail/sec-probes-ryan-cohens-bed-bath-beyond-trades-e9f35b81.

[2] In re Bed Bath and Beyond Corp. Sec. Litig., 2023 WL 4824734 at 2.

[3] Ryan Cohen (@ryancohen), Twitter (Jul. 19, 2021, 7:48 PM), https://twitter.com/ryancohen/status/1417315406272864258?lang=en.

[4] In re Bed Bath and Beyond Corp. Sec. Litig., 2023 WL 4824734 at 2.

[5] Id.

This post comes to us from Sue S. Guan, the Albert J. Ruffo Assistant Professor of Law at Santa Clara University School of Law. It is based on her recent paper, “Finfluencers and the Reasonable Retail Investor,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog