In the global effort to protect the earth’s climate, the pace of regulation is rivaled only by the speed of technological innovation.

What seemed improbable just a few years ago – requiring large companies to measure and report annual greenhouse gas emissions generated by their operations and “value chains”– is becoming reality in several countries.

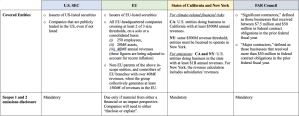

While the SEC’s climate disclosure rules are pending, and will probably face litigation when final, regulations from other agencies and jurisdictions are likely to affect U.S. companies soon:

- The European Union’s “Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive” (CSRD), which goes into effect in January,

- the Federal Acquisition Regulatory (FAR) Council’s November 2022 proposal on “Disclosure of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate-Related Financial Risk”,

- California’s new “Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act” (SB 253) and “Climate-Related Financial Risk” statute (SB 261), as well as its “Voluntary Carbon Markets Disclosures” bill (AB 1305), all signed into law in October, and

- New York State’s twin bills for a “Climate Corporate Accountability Act” (S897-A) and a “Climate-related financial risk and required disclosures” statute (S5437), which may be approved in the coming months.

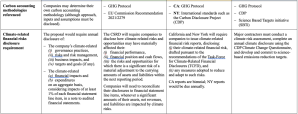

All these regulations will require companies to make disclosures similar to those at the heart of the SEC’s March 2022 proposal “on The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate Risk Disclosure:”

- the risks and higher costs companies expect to face as a result of climate change (so called “climate-related financial risks”), and

- their greenhouse gas emissions data (including Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3[1]).

A Simplified Comparison

Key Differences

- Consolidation – Both the EU and U.S. regulators consider a company’s size in determining which entities are subject to the measures, how soon those measures apply, and what information those companies are required to disclose (with more disclosure expected from larger entities).

- EU – The CSRD sets remarkably low thresholds overall. Further, these thresholds apply on a consolidated basis, meaning that the revenues, assets, and employee totals must be added up across an entire group. In addition, non-EU groups will need to report at the level of their ultimate holding company for CSRD reporting purposes.

- California – California has set a much higher size-threshold than the EU ($1 billion for emissions reporting, and $500,000 for climate-related risks) but does not indicate how it should be calculated. Implementing rules must still be issued by the California State Air Resources Board (CARB) in the coming year and may direct the use of consolidated-group figures. If CARB does not so indicate, the number of covered companies will be significantly smaller.

- New York State – New York follows California’s revenue thresholds; however subsidiaries’ revenues are explicitly included in the count.

- SEC – Unlike the other three measures, the SEC’s proposed rules would apply only to publicly-traded companies. The rules will be phased in gradually based on an issuer’s size, determined by the value of its public float.

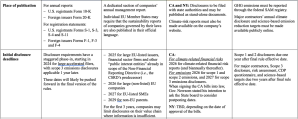

- Group-level disclosures – With one exception, these measures also require reporting to be done on a consolidated basis.

- SEC – Under the SEC’s proposed rules, securities issuers would report on climate in the aggregate, on behalf of themselves and their controlled subsidiaries, just as they do for their financials.

- California and New York – The same principle will likely apply in California and New York. Once a company is covered (by virtue of whatever consolidation methodology), it will need to disclose aggregate climate risks and emissions for itself and its subsidiaries.

- EU – The EU will apply the same principle on a first level. However, the CSRD includes a separate provision (Article 40a) that will require groups to report also at the level of their ultimate holding company, regardless of where that holding company may be headquartered or listed, as long as the group generates a significant aggregate revenue on EU soil. This provision casts an extraordinarily broad net – although it will be at least 6 months (until the implementing standards for Article 40a are released) before the requirements are clear on what ultimate parent reports must include for non-EU groups (and particularly whether they must include group-wide emissions).

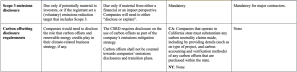

- Materiality qualifier (from most to least stringent):

- California and New York State – California and New York (if passed) will require disclosure of Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions.

- FAR Council rules – The FAR would also require public emissions data, although Scope 3 only from major contractors.

- SEC – Scope 1 and 2 emissions disclosure would be mandatory for all SEC registrants. Scope 3 would be required only if the emissions are “material”.

The materiality qualifier is consistent with the SEC’s definition of financial materiality and the relevant U.S. Supreme Court precedents and so should be tied to the “substantial likelihood” that a reasonable investor would consider the data important when making an investment or voting decision. The SEC notes that disclosure of Scope 3 emissions may be necessary to give a complete picture of a registrant’s climate-related risks.

-

- EU – The CSRD will require disclosure of Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions only to the extent that a company deems each relevant from a double materiality perspective – meaning from both a financial and a climate-impact perspective. The climate-impact disclosure will likely be broader. When assessing impact materiality, companies are expected to consider the needs of all their “stakeholders” – which include “civil society, NGOs, governments, analysts and academics”.

It is important to note that the different materiality assessments of these disclosure regimes could yield varying results.

Some companies (for example, those in heavy industry, depending on their particular customer pool) may only deem Scope 1 and 2 emissions material to their activities, while for others (such as transportation companies) material emissions will all be under Scope 3. The failure to disclose one or more categories will of course hinder comparisons between companies and may result in an incomplete picture of a firm’s emissions and transition risk.

- Carbon accounting methodologies:

- EU – The EU Directive allows companies to apply GHG Protocol accounting methodologies on a par with the International Standardisation Organization’s (ISO) 14064 guidance on GHG, and the EU Commission’s Recommendation (EU) 2021/2279 on environmental footprint methods. Although these frameworks are similar, their wording and degree of specificity vary (with the GHG Protocol being more detailed and prescriptive than the rest), opening potentially to a varying interpretation of what are in practice minutely precise accounting and consolidation techniques.

- California – The California statute references the GHG Protocol – with an added, somewhat ambiguous reference to “an alternative standard, if one is adopted after 2033”.

- New York State – The New York bill references the GHG Protocol, standards developed by CDP Global, and any rules that may be adopted by the SEC.

- FAR Council – FAR similarly references the GHG Protocol, CDP, and other leading international carbon accounting frameworks

- SEC – While the proposal was based on the GHG Protocol, the SEC did not adopt all its features and left companies free to design the carbon accounting methodology that is best suited to their activities, as long as they disclose the underlying principles and assumptions.

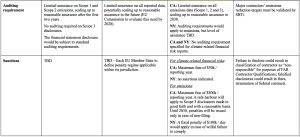

- Auditing – Given the variations on this front, it is likely that the bar on emissions data assurance would be set by the framework with the highest verification standards, which is currently California, requiring reasonable assurance on Scope 1 through 3 from 2030 onwards.

- Sanctions – This is where regimes are most likely to vary. Importantly, the sensitivity and novelty of these frameworks increase the likelihood of discrepancies in enforcement style and administrative consequences across jurisdictions.

The Pull Effects of Vanguard Regimes

Given the fragmented, rapidly evolving policies, multinational corporations subject to multiple emission-disclosure regimes may have to comply with separate frameworks at once.

Hypothetically, a conglomerate may have to calculate emissions and report them once at the level of its EU entities or EU sub-group (and separately, in the case of distinct EU sub-groups), another time always in the EU, at the level of its non-EU ultimate parent company (where different, or where a different consolidation perimeter applies), and (possibly, several) other times at the level of its U.S. entities (perhaps on consolidated group activities, perhaps not, perhaps both), each time under different national or state reporting rules.

Take Sony. The group would likely be caught (i) once by EU CSRD rules, at the level of Sony Europe B.V. (disclosing for itself and its subsidiaries), (ii) once more by CSRD rules (although this time under presumably simplified Article 40a reporting standards), at the level of its Japanese parent, Sony Group Corporation (disclosing on the behalf of the entire group), and (iii) potentially several more times for any entities that are either (a) registered as securities issuers with the SEC (according to available EDGAR data, these are Sony Group Corporation, Sony Corp. of America, Sony Financial Holdings Inc., and Sony Music Entertainment Inc.), (b) active in California or New York, or (c) U.S. federal government contractors.

Some frameworks make allowances for this anticipated overlap. The California laws will allow covered entities to submit reports generated to comply with substantially similar federal rules (such as the FAR Council or the SEC climate disclosure rules, if they are passed). The EU Commission is responsible for developing an international equivalence framework that would allow companies to submit climate reports prepared under competing frameworks like the SEC rules – although these would likely need to be supplemented to cover the many other ESG-related disclosure requirements that are built into the EU Directive.

Best practices for climate disclosure will likely converge. We reference Brussels’s and California’s well-known “pull” effect, which drives a general shift of corporate behaviour toward jurisdictions with the most stringent regulatory standards. These effects could be particularly strong here, given the significant overlap among the companies covered by each framework.

Data substantiates a large potential overlap. Over 6,000 companies are registered with the SEC (most of them U.S.-headquartered). The EU Commission had originally estimated that 4,000 foreign securities issuers would be covered by the CSRD. Article 40a brought the estimated number of foreign in-scope companies to 10,000 – about one-third of them U.S.-headquartered. The California statute should cover 5,000 U.S. companies for emissions disclosures ($1 billion threshold), and 10,000 U.S. companies for climate-risk reports ($500,000 threshold). An October report by Public Citizen estimated that 75 percent of Fortune 1000 listed companies fall within the scope of the California rules. Similar considerations apply to New York. The FAR Council anticipates that over 5,700 significant and major contractors will be affected by its proposed rules. Most companies caught by these different-sized pools will likely be the same entities.

An Opportunity for SEC Leadership

The SEC’s rulemaking authority rests on the powers granted to it under sections 7, 10, 19(a), and 28 of the Securities Act, and sections 3(b), 12, 13, 15, 23(a), and 36 of the Exchange Act. These federal regulations allow the SEC to require that U.S. securities issuers make all disclosures that are “necessary or appropriate in the public interest or for the protection of investors.”

The commission first found that environmental disclosure could promote investor protection in 1973. Given today’s heightened climate emergency, and the markets’ clear perception of climate risk as a source of financial vulnerability and volatility, this mandate should be apparent from a simple reading of the commission’s statutory authority.

There is a compelling case for the SEC to take responsibility for harmonizing climate disclosure regimes in the interest of investor protection. As Prof. Joseph Grundfest observed in his recent comments to the SEC proposal, the SEC’s rulemaking could serve as a standardized “clearing house” for the various climate disclosures issued by registrants, whether voluntarily or mandatory. Well over 30 countries have adopted or will soon adopt climate disclosure rules. Mandating disclosure in the presence of private ordering is a common occurrence, consistent with the SEC’s historical approach to developing disclosure rules. Indeed, this is what the commission did with respect to international financial reporting immediately after its inception, starting in the 1930s and leading to GAAP.

Any rules the SEC proposes must facilitate efficiency, competition, and capital formation – which is why the SEC must also conduct a cost-benefit analysis. Compliance with the SEC climate disclosure rules should not, for most registrants, require significant additional costs, as a large percentage of U.S. registrants, and most groups with foreign operations, will soon be publicly disclosing more emissions data than the SEC proposes to require, even if the commission’s rules never take effect. This is without considering that, in the 20 months since the SEC proposal was released (and the SEC’s first cost-benefit analysis conducted), the percentage of companies that are voluntarily disclosing their emissions and climate risks has risen substantially. In parallel, the cost of acquiring climate and emissions data has declined and will continue to decline. The SEC is poised to lead globally in protecting investors from climate-related financial risk and ensuring a harmonized approach to climate disclosures – which are only destined to become more relevant and widespread.

Beyond Investor Protection

It is difficult to say whether leadership on climate will come from the SEC. The fact that FAR will likely end up being the more incisive – and more durable – disclosure regime at the U.S. federal level merits consideration. Beyond investor protection, the adaptation and mitigation of climate change is an urgent matter of environmental and industrial policy. Citizens and future generations need courageous and incisive climate policy, regardless of whether and how they may be affected by financial investment strategies and returns. The CSRD is a tool built with that ambition. The U.S. should take stock.

ENDNOTE

[1] The GHG Protocol categorizes corporate greenhouse emissions into three broad scopes, which are the most widely used reference framework for carbon emissions accounting:

- Scope 1 = All direct GHG emissions originated by a company’s own activities;

- Scope 2 = Indirect GHG emissions from consumption of purchased electricity, heat or steam; and

- Scope 3 = Other indirect emissions that occur in the reporting company’s broader “value chain”, both upstream and downstream. The value chain can include activities related to the extraction and production of purchased materials and fuels (and so potentially direct and indirect suppliers), transport-related activities in vehicles not owned or controlled by the reporting entity, electricity not covered in Scope 2, other outsourced activities, and even the emissions tied to the use of products sold (estimated over the life of the product) and waste disposal activities.

This post comes to us from Clara (Charlie) Cibrario Assereto, a practicing lawyer in the EU, a founder of the global sustainability practice at Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP, and an adjunct professor at Columbia Law School, and from Cynthia Hanawalt, the director of climate finance and regulation at Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law and former chief of the Investor Protection Bureau for the New York State Office of the Attorney General.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog