Business is a team sport, and the schools that teach it understand this: They generally orient their assignments, their grades, and their classes around collaboration.

Law schools do basically none of these things. We train and assess law students as individuals: With few exceptions (e.g., moot court or journals), their classwork, their tests, and their job opportunities hinge on their ability to succeed as individuals. Is law an individual sport?

In a new study, we look at dealmakers in law firms, examining the individual characteristics that distinguish those who lead M&A deals. We find that successful leaders of a firm’s significant deals rarely lead alone. Their characteristics include having:

- greater current value (making money and cementing claims of expertise),

- higher prospective value (cultivating clients and attracting future clients and employees), and

- more substantial stakeholder value (retaining star attorneys and burnishing their reputations).

Firms tend to tout significant deals, so we look at their press releases to assess the importance of leadership teams versus individual leaders.

Our database includes news announcements issued by six AmLaw 200 law firms – Cravath, Swaine & Moore; Hunton Andrews Kurth; Paul, Weiss; Shearman & Sterling; Sullivan & Cromwell; and White & Case – between 2013 and 2023, inclusive. Our data represents over 50,000 lawyers on more than 10,000 unique deals.

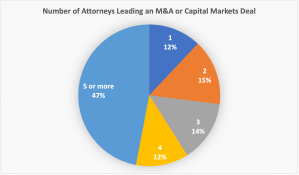

We find that deals, by the firms’ own account, are led by a team of lawyers rather than a single person. Three out of four deals (74 percent) are led by three or more lawyers. Only about one in 10 (11.6 percent) is credited to a single lead lawyer. The average deal leadership team has five attorneys: the power five.

Leadership teams are horizontal and vertical. Peers, as reflected in seniority and title, collaborate. Two or even three partners are on team. Yet teams are not only horizontal in their organization but also vertical. The hierarchical structure facilitates functional goals, such as efficient division of labor, productive cooperation, and reduced conflict. Just as the horizontal structure is visible in a team of equals (partners), so too is the vertical structure visible in the inclusion of junior lawyers (associates) in lower spots on a team. The press releases also describe co-equal positions as well as superior and secondary roles within a team.

Leadership teams are diverse:

- One-quarter of deal leaders earned their law degree outside the United States.

- More than one-quarter of deal leaders are women.

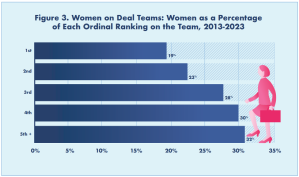

Leadership teams are moving toward gender parity:

- Deal teams are nearly twice as likely to include women today as they were in 2013; while only 42 percent of such teams had women on them 10 years ago, 78 percent did in 2023.

- Women who are on deal leadership teams are as likely as men to be “superstars”. A superstar is an attorney who is the first chair on multiple deals. Of the top 25 superstars, for example, 5 are women, or 20 percent, the same as their overall representation in the first position.

- Women associates appear more likely than male associates to be on deal teams.

- Women are moving up the deal hierarchy, as reflected in the figure below from our new essay forthcoming in the Vanderbilt Law Review En Banc.

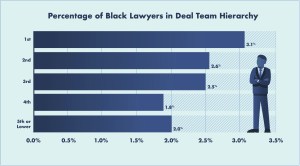

Leadership team diversity, however, is limited. While 80 of every 100 deal leaders are White, only two out of 100 are Black. By contrast, eight of 100 law students and six of 100 law firm associates are Black. The number of Black partners approximates the number of Black deal leaders (two out of 100). But this ratio compares unfavorably with that of women, a greater proportion of whom serve on deal teams than are partners. Black lawyers also do not appear to be advancing up the deal hierarchy as quickly as women, with increasingly fewer working in lower ordinal positions on leadership teams.

Law is a team sport. The success of lawyers is based on their ability to collaborate, to be part of a team. Being picked for a team is often a necessary – though not sufficient – condition for making partner or otherwise being promoted within the firm. When we view deals from a team perspective, rather than looking solely at the lead lawyer spot, we see increasing numbers of international lawyers and women lawyers showing up as part of the deal leadership teams.

Landing on the right team likely matters (a lot). A lesson the three of us learned a long time ago on the playground (and in our careers) is that getting on a team is crucial to competing, and joining the right team is key to remaining competitive. Being excluded from teams, let alone the right team, can be fatal to success. The competition in the legal market is, for the most part, among teams. Yet, in law schools, we do next to nothing to train our students to work well on teams. That’s nuts, and it fails to prepare our students for the increasingly competitive legal market.

This post comes to us from professors Tracey E. George at Vanderbilt University Law School, Mitu Gulati at the University of Virginia School of Law, and Albert Yoon at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law. It is based on their recent paper, “The Power Five: The Making of Newsworthy Deal Teams,” available here. Infographics created by Michael Glowacki of EXIST Design.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog

As a practitioner who earned a J.D. in Argentina, an LL.M. in the US, and finally another J.D. in the US (and a person who’s taught Finance law in Argentina and cares massively about teaching law and pedagogy generally), I feel confident when I say the US model is individualistic and quite adversarial, not collaborative or team-oriented, and often far removed from the practice (with notable exceptions, e.g., the Derivatives course with Devi Koya I took at Northwestern was team-oriented and (now I know) close to the practice, but most of us were a bit confused and disoriented, are we supposed to get together and reach a consensus and we will all be graded based on it?). Law school in the US model is closer to the skillset a law professor or legal researcher would require (which is absolutely fine, I wish I were on that career path, but statistically unlikely for most law grads). Law is more and more a team sport, more than it was 50 years ago, even more than it was 20 years ago, because of the increasing complexity of the law and the “cultural” world the law must try to govern. Now we have NFTs! A different analogy: There are more and more pieces to the Law puzzle, and they are getting smaller and smaller and quirkier in shape, which means there is “entropy” exerting pressure. There are no “Renaissance” lawyers, and there could never be in this legal landscape.