The U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizens United v. FEC decision, along with the SpeechNow.org v. FEC court decision, reshaped the landscape of political contributions. By striking down limits on independent expenditures, these rulings opened the door to a new, opaque channel of political influence: dark money. Unlike traditional campaign contributions and lobbying efforts – both of which must be disclosed – dark money spending has no limits on contribution amounts and no requirements for disclosure.

In a new study, we examine how firms use dark money. We hand-collect data on dark money contributions by S&P 500 firms from 2008 to 2022 and find overall a marked rise in the reported use of those contributions by these firms during the past 15 years. Our results explore how this form of political influence interacts with more widely studied types of political activity. We also study the potential benefits received by firms.

The Rise of Dark Money

Before 2010, firms had two main avenues for political engagement: political action committee (PAC) contributions and lobbying expenditures. Following the 2010 federal court rulings, dark money groups, often structured as 501(c)(4) social welfare organizations or 501(c)(6) trade associations, enabled firms to make unlimited contributions for political purposes. Firms are not required to disclose these contributions. In contrast, PAC contributions are tightly regulated and capped at $5,000 per candidate each election. Lobbying is another form of political activity for firms, which has no limits on expenditures, yet they are subject to disclosure under the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995.

The data reveal how quickly dark money has emerged. The number of firms reporting dark money contributions has steadily increased since the federal court rulings, reaching nearly 25 percent of companies in the S&P 500. These firms reported contributions totaling $2.1 billion across 23,483 transactions. This is a conservative estimate, as many firm disclosures omit specific amounts.

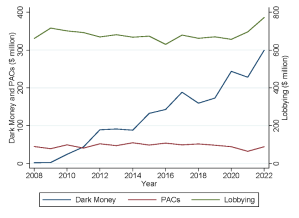

Notably, dark money does not replace PAC contributions or lobbying but complements them. In the figure below, PAC spending has remained constant throughout the sample period, and lobbying expenditures have been stable. In contrast, dark money has surged to nearly $300 million annually as of 2022. We also find considerable persistence in dark money contributions. Overall, the results suggest that firms previously faced limitations in their political activity and expanded spending using dark money.

Who Uses Dark Money?

Case Study: Sempra Energy

Sempra Energy, a prominent exporter of liquefied natural gas, reports both traditional political activity and dark money donations. Post-2010, Sempra began contributing to multiple dark money groups while continuing its existing PAC and lobbying efforts. In 2013, it secured a $2.2 billion property tax exemption for a new export facility. This illustrates how firms can layer dark money on top of traditional political expenditures to receive government resources.

Firm Profiles

We examine the characteristics of firms disclosing dark money contributions:

- Larger, older firms: On average, dark money contributors have double the assets and are about six years older relative to firms that do not disclose dark money contributions.

- Higher leverage and lower tax bills: These firms carry more debt and pay comparatively less in taxes.

- Fewer growth opportunities: On average, dark money contributors are less profitable and have lower investment opportunities as measured by Tobin’s Q.

- Bigger political spenders overall: Dark money contributors spend more on PACs and lobbying, suggesting these are complementary strategies.

Why Do Firms Disclose Voluntarily?

If disclosure isn’t required, why reveal these contributions at all? Here, we appeal to the economics of voluntary disclosure. The key factor is proprietary cost – the reputational or market penalty a firm risks if negative information surfaces later. First, we find that firms already disclosing non-required information (for example, detailed information about their board members) are significantly more likely to report dark money. This suggests that other voluntary disclosures may increase firms’ likelihood of revealing dark money contributions. Second, we observe that if an industry peer discloses a dark money contribution, the likelihood of a firm disclosing rises, consistent with peer effects. Third, we also show that firms with relatively more informed investors (as proxied by higher institutional ownership) are less likely to disclose dark money spending.

The Payoff: Contracts and Subsidies

Political connections may provide benefits to firms in several ways. Our paper studies how benefits, particularly procurement contracts and government subsidies, may accrue from dark money contributions. Contracts awarded by the federal government are economically large. Previous literature has shown that firms with political connections receive more contracts and preferential renegotiation. Additionally, sizable government subsidies are awarded to firms.

We find several key results. First, firms contributing to dark money groups are 25 percent more likely to secure federal procurement contracts. On average, their contract amounts more than doubled. By contrast, there is no effect for PAC contributions, while lobbying is strongly correlated with procurement contracts. Second, firms connected to dark money groups receive more subsidies, including grants and tax credits. Here again, PAC contributions have no effect, while lobbying increases subsidies, though to a lesser degree.

Finally, we explore the association between industrywide political activity and government resource allocation. We find that dark money is positively related to industrywide subsidies, where contributions increase the flow of subsidies across the entire sector. On the other hand, lobbying correlates strongly with the distribution of federal contracts across industries. This evidence suggests that long-term relationships facilitated by lobbyists might be comparatively more important for procurement contracts.

Implications

As dark money has risen in importance as a form of political influence, the issue has received more attention from policymakers. The Securities and Exchange Commission recently considered disclosure requirements for political contributions. Further, Congress has discussed legislation to curtail dark money contributions. Our research, along with future work, aims to shed light on this new and evolving source of political connections.

This post comes to us from Matthew Denes at Carnegie Mellon University’s Tepper School of Business and Madeline Marco Scanlon at the University of South Carolina’s Darla Moore School of Business. It is based on their recent paper, “Shining a Light on Firms’ Political Connections: The Role of Dark Money,” published in the Review of Corporate Finance Studies and available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog