From 2004 through 2010, the number of appraisal petitions filed in Delaware rose and fell roughly in parallel with the overall level of merger activity, with appraisal rights being asserted in about 5% of the transactions for which they were available. In 2011, however, the rate of petitions more than doubled (to 10%) and it has continued to increase. In 2013, 28 appraisal petitions were filed in Delaware, representing about 17% of appraisal eligible transactions. In 2014, so far, more than 20 appraisal claims already have been filed in Delaware. The amounts at stake in appraisal actions have increased as well, with the value of dissenting shares in 2013 ($1.5 billion) being ten times the value of dissenting shares in 2004, and more than five times the value of dissenting shares over their highest point in the last five years. Of the eight appraisal proceedings between 2004 and 2013 that involved more than $100 million worth of dissenting shares, four of them occurred in 2013.[1]

Most of this increased activity has come from so-called “appraisal arbitrage” – a new and expanding phenomenon of shareholder activists and hedge funds focusing on appraisal claims as a kind of investment in and of themselves. In its most common form, a large equity stake in a target company is acquired after the announcement of a merger (often just before the shareholder vote on the merger) for the sole purpose of making, or threatening to make, an appraisal claim, often accompanied by a call to other investors to join in seeking appraisal rights. Appraisal arbitrage now commonly affects the public dynamics surrounding challenges to deals and can have a significant effect on the certainty of and ultimate price paid in a deal.

A number of funds have been established that are devoted exclusively to appraisal actions as independent investment opportunities. Merion Capital LP, which has filed more than ten Delaware appraisal actions, in late 2013 reportedly raised $1 billion for a fund dedicated to appraisal claims. Major mutual funds and insurance companies – institutions that have not been significantly involved in standard stockholder litigation – also have recently filed appraisal petitions.

Appraisal litigation historically has been considered to be risky and costly. First, the wide discretion the court has under the statute to determine fair value makes the outcome of appraisal proceedings unpredictable. Fair value for these purposes is the going concern value of the company assuming the transaction giving rise to appraisal rights had not occurred (that is, excluding the value of synergies and a control premium). The trial usually involves a “battle of the experts” on both sides, with the burden ultimately on the court itself to make the determination of fair value, based on any methodology generally considered acceptable in the financial community. The methodology most often used by the court to determine going concern value is a discounted cash flow analysis, which is based in large part on assumptions and projections that themselves can be highly uncertain, including the company’s internally generated projections and speculative data about how the company would have performed if the merger had not occurred.

Also, there are strict procedural requirements mandated by the statute and the process is typically quite lengthy and expensive. A key limiting factor to the attraction of appraisal actions has been the long period of time that a dissenting shareholder has its investment tied up while the proceeding is pending. The process usually lasts two to four years and involves a multi-day trial on the merits with extensive testimony from financial experts on both sides, as well as post-trial briefing and arguments. Importantly, unlike other litigation challenging a deal, stockholders are unable to proceed as a class and shift attorneys’ fees to stockholders as a whole or to the defendants.

Factors that appear to be contributing to the increased popularity of Delaware appraisal claims in recent years include the well above market statutory interest payable on appraisal awards (5% above the Fed discount rate, compounded quarterly and accruing from the closing date of the transaction to the date the appraisal award is actually paid); increased stockholder challenges of all types to deals generally; an increase in the number of going private, management-led buyout and controller transactions, where conflicts of interest create skepticism about the deal price; and the willingness of the Delaware courts to consider a wide variety of arguments as to why fair value in a given case should be more than the merger price, often leading to appraisal awards higher than the merger price. A key factor, however, appears to be the increased involvement of shareholder activists and hedge funds in mergers and acquisitions activity generally, as they seek new ways to utilize capital and maximize profits.

As shareholder activists acquire large equity stakes in companies in anticipation, or after announcement, of a bid for a company, appraisal rights offer a route to increased profit if a board negotiates a lower than expected price. Moreover, appraisal offers an alternative route to profit – without the challenge of having to prove any wrongdoing in connection with the transaction – if a breach of fiduciary duties action against a board is not successful. The basic arbitrage opportunity presented by appraisal rights stems from the Court of Chancery’s 2007 Transkaryotic decision, where the court, against expectations, held that investors that buy target company shares after the record date for the vote on a merger can still assert appraisal rights. This decision provided the foundation for activists and hedge funds to emerge as “appraisal investors”, delaying until the date of the stockholders meeting a decision on whether to buy target company stock for the purpose of pursuing an appraisal action. With this timing advantage, investors can review information in the company’s proxy statement relating to its sale process and fairness of the price, can assess any pre-closing shareholder litigation that has been commenced, and can evaluate market, industry and target company conditions at a time much closer to the merger closing date (as of which time the court will determine fair value in an appraisal proceeding) as compared to the time when the deal price was negotiated and then voted on.

Even the threat of appraisal actions now commonly affects deal dynamics. Activists publicly and aggressively encourage other stockholders to join in an appraisal proceeding, increasing the threat of the proceeding to the target board – and thus, as a result, the activist’s leverage in negotiating a settlement. Companies face significant risks that an appraisal proceeding may lead to a large appraisal award (even more problematic if financing arranged for the transaction will not be sufficient), or may lead to the transaction not being approved by the requisite stockholder vote (even more problematic if the required vote is a majority of all outstanding minority shares, since stockholders who want to seek appraisal cannot vote in favor of the merger). These risks prompt many companies to reach settlements (which often are large) with shareholders seeking appraisal rights. In the Dell going private transaction, for example, the threat by Carl Icahn and others to seek appraisal of the shares they had amassed after announcement of the deal effectively blocked the required shareholder vote (a majority of the minority shares outstanding) and led to a $400 million increase in the merger price paid to shareholders (as recently discussed publicly by legal counsel to the Dell special committee).

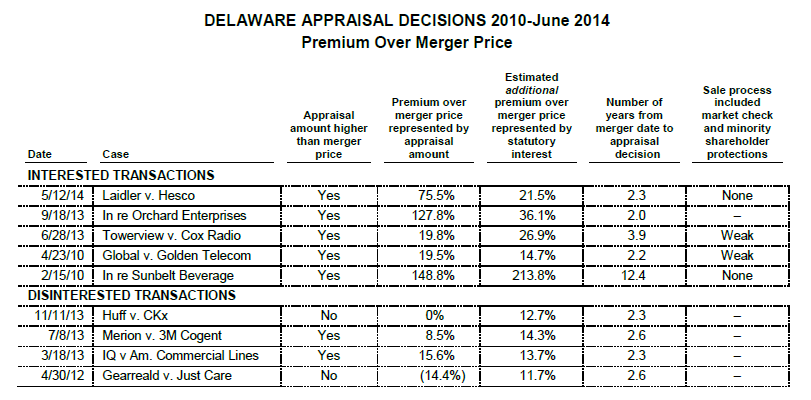

In our review of Delaware post-trial appraisal decisions from 2010 to June 2014 (see the Chart below), we found that the court’s determination of fair value was higher than the merger price in seven of the nine cases. The highest premium represented by the appraisal award over the merger price was 148.8% – without even considering the award of statutory interest (which, in that case, represented an additional premium of 213.8% above the merger price). There was only one case in which the appraisal award was lower than the merger price (representing a 14.4% discount to the merger price); and only one case in which the appraisal award was the same as the merger price.

In our review, in the five cases that the court viewed as “interested transactions” (i.e., controlling stockholder or parent-subsidiary mergers), the appraisal award was significantly above the merger price – with premiums of 19.5%, 19.8%, 75.5%, 127.8% and 148.8%, respectively, above the merger price. Taking into account the statutory interest awards in these cases, there was an additional premium of approximately 14.7%, 26.9%, 21.5%, 36.1% and 213.8%, respectively. While the extent of the market checks and protections afforded to the disinterested shareholders in these transactions varied, the range was from none to relatively weak. Notably, the two highest fair value premiums (148.8% and 75.5% – we have excluded the 127.8% premium because it was based almost entirely on an issue relating to interpretation of preferred stock terms and so is not relevant in this context) were awarded in the only two cases in which there were no market checks or minority protections whatsoever. For example, the backdrop to the case in which the 148.8% premium was awarded was an arbitration panel determination that the only reason for the merger was to eliminate the petitioner as the sole remaining minority shareholder – “without notice and without legal justification … [and through the controlling stockholder’s use of] strong-arm tactics.”

By contrast, in the four transactions viewed by the court as “disinterested” (i.e., third party arm’s length transactions), the fair value determination was higher than the merger price in only two of them. These premiums, 8.5% and 15.6%, were considerably lower than the premiums in the interested transactions.

In the disinterested case in which the appraisal value was equal to the merger price, the court said that it had no choice but to use the merger price as the basis for fair value because there was no data to support the parties’ proposed financial analyses (as the company had never prepared projections in the ordinary course of business and had a highly unpredictable business); and the court viewed the merger price as a reasonable measure of fair value because there were no conflicts of interest and the sale had been subjected to a full market check through a competitive auction. In the disinterested case in which the appraisal award represented a 14.4% discount to the merger price, the merger price had been based on projections that had been prepared by the dissenting shareholders themselves – the former CEO and CFO of the target company, who, the court found, had prepared the projections while strenuously campaigning for a standalone option for the company so that they would not lose their jobs, and who, as directors, had voted in favor of the merger before they voted against it as shareholders.

Critically, notwithstanding the notable increase in appraisal activity, it is still only a fairly low percentage of all appraisal eligible transactions (17% in 2013) that currently attract appraisal petitions. (By contrast, almost all strategic transactions now attract litigation with breach of fiduciary duty claims.) Moreover, while the only consideration in an appraisal proceeding is the determination of fair value (and wrongdoing by the target board or flaws in the sale process are legally irrelevant for these purposes), the transactions that attract appraisal petitions generally involve some basis for a belief that the deal price significantly undervalues the company – that is, transactions involving controlling stockholders, management buyouts, or other transactions for which there did not appear to be a meaningful market check or significant minority shareholder protections as part of the sales process. Andrew Barroway, founder and CEO of Merion Fund, one of the most prolific of the hedge funds dedicated to filing appraisal petitions, has said that Merion looks for deals that appear to be undervalued by at least 30% and focuses on management-led buyouts. “The vast majority of deals are fair. We’re looking for the outliers,” he has been quoted as saying. In our review, the transactions leading to appraisal awards significantly higher than the merger price were “interested transactions” and involved a less than rigorous sale process.

Some of the practical implications of the rise in appraisal arbitrage are:

(a) Need to consider the likelihood of appraisal petitions and the possible effect on the transaction. In general, acquirors must evaluate the possibility that appraisal proceedings are likely to be a component of the process in mergers and acquisitions transactions. If a transaction has been subject to an aggressive competitive process and the deal price is generally viewed as being high, the pursuit of appraisal then would seem more unlikely. At the other extreme, a transaction with a company controller or a private equity deal with major management participation would be a probable suspect for the assertion of appraisal rights, particularly if the sale process appears to raise questions. Other transactions between these extremes will require a careful evaluation of the facts and circumstances to determine the likelihood of appraisal rights being sought and, if so, the possible effect on the transaction.

The obvious advice is that buyers need to build into their financial models the possibility of an appraisal award after the transaction closes. The advice is problematic, however, given both the effect on the bid’s competitiveness and that the amount of the appraisal award (plus the above market interest) can be very significant. The anticipated internal rate of return for a transaction can be significantly adversely affected by an unanticipated post-closing cost (whether due to a court determination or settlement of an appraisal claim or of fiduciary litigation), and it is very difficult to model for such an outcome. Importantly, appraisal settlements are increasingly difficult to reach as investors focus on the benefits of the above market interest rate that accrues until payment of the appraisal award.

(b) Increased risk and uncertainty for transactions. The increased strategic use and threat of appraisal actions can increase uncertainty and risk both for buyers and sellers. Closing uncertainty for both sides increases with inclusion of an appraisal rights condition (see (c) below). Without an appraisal rights condition, buyers are faced with the uncertainty that a significant payment may become payable to dissenting shareholders post-closing; that arranged financing may not cover the full required payment to shareholders (because the amount payable to dissenting shareholders will be uncertain even after closing); and that a shareholder vote requiring a percentage of all outstanding disinterested shares may not be obtainable (because dissenting shares cannot vote). Moreover, investors can threaten appraisal without later following through – providing a no-cost route to exerting the pressure that results from actually bringing an appraisal action.

Importantly, the company’s sale process, as well as the range of fairness established by the target company’s bankers, is unknown to the buy-side party until the company’s proxy statement is furnished to shareholders. A buyer – for example, a private equity firm in a management-led buyout (where the court can be expected to be skeptical of the transaction) – may want to try to avoid attracting appraisal petitions by offering a price at the high end of the fairness range and by acquiescing in (or even encouraging) a robust sale process by the seller. Critically, however, even in this case, the buyer has no certainty as to whether the seller may have improperly prepared the company projections, conducted the market check or dealt with any conflicts, or otherwise may have acted in ways that could render the process unreliable – and thus invite appraisal demands. Buyers, particularly those in transactions that will be most at risk for attracting appraisal petitions, may begin to seek ways to obtain some protection in this area, such as, possibly, including representations as to the process in the merger agreement or requiring information about the process before signing the merger agreement.

In addition, there is significant uncertainty about how the court will determine fair value in any given case. In two of the most recent proceedings, the court in one case, in a break with past practice, used the merger price in determining fair value (in fact, the court used it as the sole factor as there were no company projections on which to base a financial analysis and there had been a full competitive auction), and in the other case the court refused to consider the merger price at all (as the merger price had been dictated by the 90% parent in a short-form merger). It is unknown, however, whether, and to what extent, a merger price will be taken into account, even in arm’s length transactions, when there is a less than perfect market check or when there are projections available for a discounted cash flow analysis or comparable companies and transactions for a comparables analysis. Presumably, a court, when it evaluates the extent to which a deal price is a relevant factor in determining fair value, will be more likely to give deference to the deal price if it was reached after an arm’s length negotiation in a pristine sale process that included an effective market check.

(c) Consideration of an appraisal condition to a merger. Acquirors may again consider use of appraisal rights conditions, which used to be common – i.e., a condition to the merger that not more than a specified percentage, often 10%, of the outstanding target shares seek appraisal rights. Of course, sellers will resist this condition as it effectively reallocates the risk associated with appraisal rights to the seller. Buyers in a competitive process will be wary to include this condition as it would be likely to significantly diminish the competitiveness of the bid as compared to bids not imposing the condition. An appraisal rights condition may be most attractive to (or even necessary for) a financial buyer or a buyer with significant financing needs for the transaction.

Importantly, it is difficult to predict the effect of an appraisal rights condition on a transaction. On the one hand, the condition helps to provide more certainty to the acquiror by limiting the potential exposure to appraisal rights. On the other hand, the condition may provide more leverage to last-minute opportunistic investors who can threaten to derail the deal by triggering the condition, thus causing more uncertainty for both the buyer and the seller. At the same time, though, it may be that activists and hedge funds will ensure that the condition is not triggered, as their least preferred alternative will be a deal that does not close (in which case they would receive neither the merger price nor appraisal rights).

(d) Possible legislative developments. In light of the significantly increased prevalence of appraisal petitions, it may be that the Delaware Legislature will consider legislative amendments to address some of the difficulties they present for buyers and sellers. Most obviously, the above market statutory interest rate could be reduced. Other possible changes could include limiting the types of transactions to which appraisal rights would be applicable or restricting the timing for filing a petition. However, there has been no indication that the Legislature is currently considering any changes.

(e) Increased need to avoid material disclosure violations. In the midst of the increased popularity of appraisal petitions, the Delaware courts have been expanding their interpretation and application of so-called “quasi-appraisal” remedies. These post-closing remedies – initially granted only for proxy disclosure violations that related to the shareholder’s right to seek appraisal and were discovered after the time to petition for appraisal had passed – are intended to put the shareholder in the same position as if the shareholder had petitioned for appraisal. The court’s expanded view of quasi-appraisal has increased the risk that disclosure violation claims will be made post-closing, with the potential for expensive appraisal-like remedies rather than curative disclosure. As a result, companies will want to redouble their efforts to avoid material disclosure violations of all types.

[1] This data is provided in the report of a new study by Charles R. Korsmo and Minor Myers, law professors at Case Western University School of Law and Brooklyn Law School, respectively, Appraisal Arbitrage and the Future of Public Company M&A, publication forthcoming in Washington University Law Review (draft Apr. 14, 2014).

(This memorandum, in expanded form, will appear in the 2014 Supplement to Takeover Defense: Mergers and Acquisitions, by Arthur Fleischer, Jr. and Alexander R. Sussman of this firm, publication forthcoming from Aspen Publishers.)

The full and original memo was published by Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson LLP on June 18, 2014, and is available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog