Law schools have become poster children for market dysfunction. As the Great Recession decimated the demand for new lawyers, a functioning market would have led most schools to reduce enrollments. Instead, the overall number of admitted students increased to more than 60,000 in 2010 – up ten percent from 2008. Three years later, the result was the largest-ever graduating class of JDs: 46,776 in 2013. Nine months after law school, only about half of them had found full-time long-term (“FTLT”) JD-required jobs.

Beginning in 2011, the ABA finally forced schools to reveal the dismal employment results for many recent graduates. As applications dropped at most institutions, some deans adopted an easy fix: increase acceptance rates to keep classrooms full. By the fall of 2014, almost 80 percent of applicants to the entering class of 2014 found a law school willing to accept them. A decade earlier, the overall acceptance rate had been 56 percent.

Top law schools whose graduates have excellent employment prospects remain highly selective. But other schools exploit the availability of unlimited federal educational loans to keep tuition high and their students swimming in debt. Perversely, some schools with the worst FTLT JD-required employment rates burden their graduates with the highest levels of educational debt. Consider this list of the student debt leaders, along with the FTLT JD-required employment rates for their 2014 graduates[1]:

| School | Average Debt (2014 Grads) |

FTLT-JD (2014 Grads) |

| Arizona Summit | $187,792 | 40% |

| Thomas Jefferson | $172,445 | 30% |

| New York Law School | $166,622 | 43% |

| Northwestern University | $163,065 | 78% |

| Florida Coastal | $162,785 | 35% |

| American University | $159,316 | 45% |

| Vermont Law School | $156,713 | 48% |

| Touro College | $154,855 | 57% |

| University of San Francisco | $154,321 | 33% |

| Columbia University | $154,076 | 87% |

| Whittier College | $151,602 | 27% |

| California Western | $151,797 | 48% |

What accounts for these diverse outcomes? The answer is law school moral hazard resulting from public policies that distort the market. In particular, the federal student loan program, the inability of debtors to discharge educational debt in bankruptcy, and the resulting lack of individual law school accountability for employment results have intersected to produce enduring human misery for many young law graduates. The weakest law schools get a big lift from prelaw students who ignore the odds, convincing themselves that they will be among the job “winners” at schools with few such outcomes. Psychologists call it confirmation bias – ignoring facts that don’t fit a preferred view of the world.

Law School Submarkets: A Tool for More Precise Thinking

Some law school deans, admissions officers, and faculty members urge that the challenges confronting law schools are overstated. Even worse, they describe the “improving market for law graduates” with an imprecision that confounds a true understanding of the issue. In fact, there is no single “law school market.” Rather, the differences in graduate employment opportunities vary dramatically across schools. The diverse characteristics of the resulting submarkets should produce meaningful differences in tuition, as well as in student willingness to incur debt for a JD. Appropriate public policies would allow the market to create those differences.

Using employment results for recent graduates, I suggest three criteria to identify three law school submarkets: 1) a school’s success in placing its most recent graduates in FTLT JD-required jobs (excluding law school-funded positions); 2) the starting salaries of graduates who obtained such jobs; and 3) the geographic dispersion of graduates who found employment.

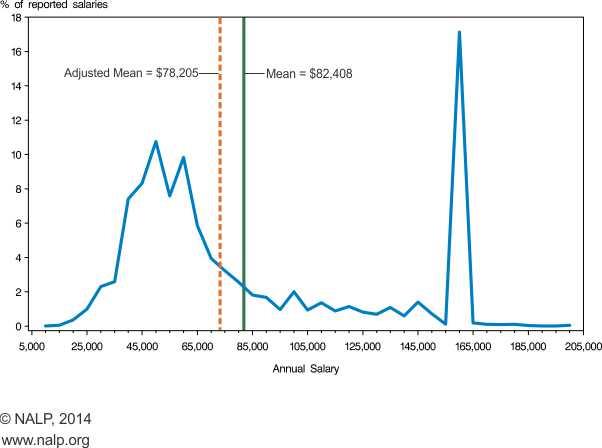

With respect to the second criterion, the submarkets reflect themselves in a bimodal distribution of law firm starting salaries for new graduates[2]:

As the graph shows, only 15 to 20 percent of 2013 graduates began their careers at big firms offering the most lucrative starting salaries – up to $160,000 a year. That becomes a key factor in identifying the first submarket – National Schools. Those 24 schools placed more than 60 percent of their 2013 graduates in FTLT JD-required jobs and at least 20 percent in National Law Journal 250 firms. Importantly, this criterion is not a qualitative determination that such positions will be the most personally or professionally rewarding. Plenty of evidence suggests that lawyers in big firms are among the least satisfied. The goal is to identify various law school submarkets, not to judge them.

Eighty-eight Regional Schools comprise a second submarket. Those schools placed at least 55 percent of 2013 graduates in FTLT JD-required jobs (the overall rate for all law schools), but fewer than 20 percent in NLJ 250 firms. At every Regional School, the top geographic placement for graduates was its home state. Collectively, National and Regional Schools accounted for 112 of 201 ABA-accredited law schools in 2013.

A final group of 89 schools comprises the Problematic Submarket. Those schools placed fewer than 55 percent of 2013 graduates in FTLT JD-required jobs. The weakest schools did much worse: 34 placed fewer than 40 percent of graduates in such positions; 13 placed less than one-third.

Policy Implications

Current educational loan and related bankruptcy policies treat all schools in these submarkets identically. The result would be comical – except that for the student victims, it’s no joke. Among the top ten schools in average student loan debt for their 2013 graduates, eight were members of the Problematic Submarket. Three placed less than one-third of graduates in FTLT JD-required jobs. Without financial skin in the game, marginal schools in the Problematic Submarket maximize revenues by filling classrooms and charging tuition that bears no relationship to their graduates’ outcomes.

Revising the current regime to unleash market forces could create meaningful differences across the three submarkets and within the Problematic Submarket. Suppose the federal loan program set a maximum allowable amount at say, $80,000 yearly for tuition and living expenses. Now add a rule that only schools placing at least 55 percent of their most recent graduates in FTLT JD-required jobs would get the full benefit of the federal guarantee (up to $80,000). Finally, require schools failing to meet that FTLT JD-required threshold to face a sliding scale downward from that limit.

Under this plan, for example, a 45 percent placement rate would qualify a student at that school for only half of the annual maximum amount (i.e., $40,000), thereby forcing the school to cut tuition and/or forcing the student to find another funding source. If the school filled that funding gap with its own loan program, all such debt would be fully dischargeable in bankruptcy without any showing of undue hardship.

Days of Reckoning

Schools with the worst employment outcomes could no longer hide behind the protective shield of federal loans and bankruptcy rules. They would have difficulty charging tuition that burdened their students with some of the highest levels of debt. They would lose the ability to exploit the moral hazard that currently accompanies the absence of accountability.

Deans, admissions officers, and faculty who believe what they are telling prospective law students – that all is well or soon will be – have nothing to fear from the proposed revisions to the current regime. If their current pronouncements are correct, they will be winners in a market that actually works. Consumers will flock to their product because it offers value, not because flawed policies produce distortions that protect the weakest schools.

Talk is cheap. Decisional errors about a young person’s future can be expensive and enduring.

ENDNOTES

[1] “Which law school graduates have the most debt?” U. S. News & World Report, Best Law Schools – 2016 (ranked in 2015), http://grad-schools.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-law-schools/grad-debt-rankings; “Employment and ABA Required Disclosures,” Arizona Summit Law School, http://www.azsummitlaw.edu/gainful-employment-and-aba-required-disclosures; “Employment Summary Report,” ABA Section of Legal Education and Admission to the Bar, http://employmentsummary.abaquestionnaire.org/

[2] The “Adjusted Mean” takes into account the fact most large law firm job salaries are reported, but about half of small firm salaries are not. Importantly, the graph includes only salaries for class of 2013 graduates who obtained full-time law firm jobs.

The preceding post comes to us from Steven J. Harper, Adjunct Professor at Northwestern University School of Law and Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences, author of “The Lawyer Bubble – A Profession in Crisis” (Basic Books, 2013), contributing editor to “The American Lawyer” and ABA’s “Litigation,” and former litigation partner at Kirkland & Ellis LLP. The post is based on his recent article, “Bankruptcy and Bad Behavior – The Real Moral Hazard: Law Schools Exploiting Market Dysfunction” (forthcoming in American Bankruptcy Institute Law Review, Vol. 23, No. 1, Winter 2015, pp. 347-365), available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog

One of the most disappointing aspects of the law school scam is the lack of leadership from the elite of the profession. The deans of top law schools should be taking the lead on fixing the problem but they are ignoring it to a man and woman. To my mind their professional and moral failure is worse than that of the deans of scam schools, who have less privilege and more to lose personally from doing what is right.

just lol at this being a privilege issue. im as annoyed as the next breh that TOPLAWDEANBREHS aren’t as involved in solving the problem, but let’s not redirect any blame away from those brehs who are actually ripping people off and ruining lives, breh.