Companies tell us they buy back stock because it is undervalued. The data, however, tells a different story.

Buybacks peaked in 2007 at $589 billion—the best time to sell. And then fell to $138 billion in 2009—the best time to buy.

More than 460 of the 500 companies that make up the S&P index bought back stock over the past decade. It is hard to believe that public companies are systemically undervalued. Much less 92% of the S&P 500.

If companies aren’t undervalued, why do they buy back stock? Taxes.

Buybacks and dividends accomplish the same goal. Both distribute cash to shareholders. The difference lies in their tax treatment. Dividends face the dividend tax. Buybacks do not.

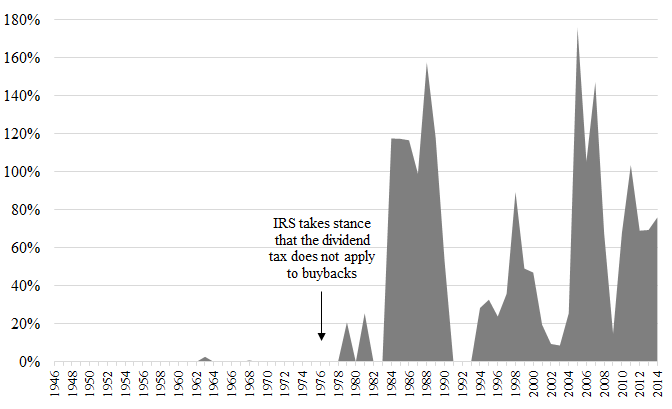

This divergence in tax treatment stems from an IRS stance taken in 1976. Buybacks were virtually nonexistent before then. Companies have since substituted buybacks for dividends to avoid tax. Federal Reserve data, shown below, charts this evolution.

This IRS stance has been taken for granted by both scholars and the tax bar. In a recent article, I argue that the IRS has misinterpreted the Tax Code. Buybacks should actually be taxed as dividends.

Sadly, the IRS’s mistaken stance incentivizes companies to gamble their earnings in exchange for a tax break. Dividends and buybacks are close, but not perfect, substitutes. Dividends are paid in cash. Buybacks, on the other hand, offer shareholders a choice—cash or company stock. The cash is taxable. The company stock is not, as long as it is held.

Imagine yourself as a RadioShack customer. You can choose to receive 100% money back as a store credit or only 85% money back as a cash refund, since RadioShack deducts a 15% processing fee. Store credit requires you to shop at RadioShack again. A cash refund can be spent at any store.

RadioShack management faced a similar dilemma in deciding whether to distribute its earnings to shareholders as a buyback or a dividend. A buyback offers shareholders 100% money back. A buyback, however, requires that shareholders reinvest in RadioShack stock. A cash dividend gives shareholders the freedom to invest in any company, but results in a dividend tax.

Management generally opted for store credit. From 1995 to 2011, RadioShack bought back $4.9 billion of its own stock. Yet the company generated only $3.9 billion in earnings over that period. RadioShack spent all its earnings on buybacks and then borrowed another $1 billion from future earnings to buy back even more stock.

On February 5, 2015, RadioShack filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Long-term shareholders were wiped out, losing two decades of earnings.

At least they avoided the dividend tax.

The preceding post comes to us from Wanling Su, Visiting Fellow at Yale Law School. The post is based on her recent article, “How the IRS Wrongly Allows Stock Buybacks to Evade the Dividend Tax,” which is available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog

The theoretical basis of Rev. Rul. 76-385 is a lot more nuanced than you discuss in your paper. The fundamental question that the IRS considered is what the rights of a very small shareholder consist of. (Incidentally, it is quite misleading for you to consistently refer to the standard of the ruling as applying to all “minority” shareholders. The ruling is quite explicit that its reasoning applies only to holders with a minimal interest). In essence, the IRS concluded that a minimal shareholder’s interest in a company is more or less linear. Each share they surrender reduces their interest in the company exactly as much as the next share. Thus, selling 10% of their position is just as meaningful of a reduction (on a per share basis) as selling 100%. Contrast this with a majority holder, who could still retain control of the corporation even if she sells some of of her shares. That shareholder has a less-meaningful reduction if she sells a number of shares that leave her with majority control, but a very meaningful reduction if she sells enough shares to take her down to 50% or below. You can disagree with this argument, but it’s not even spelled out in your paper. You just have tables showing the mathematical results from a bunch of cases.

In addition, you seem to misunderstand the tax benefits of buyback treatment, which leads you to make the wild assertion that companies “would never” conduct buybacks were it not for Rev. Rul. 76-385. The tax benefit of Rev. Rul. 76-385 is NOT deferral. Even if section 302 applied to treat a buyback as a dividend, it would NOT affect the taxation of a nonselling shareholder. The only effects of redemption as opposed to dividend characterization pertain to the selling shareholder. Specifically, the shareholder can reduce their gain by their basis in the redeemed shares, can use capital losses to offset the gain, and ,if they are foreigners who don’t hold the shares in a U.S. trade or business, are not subject to dividend withholding tax. If a corporation buys back shares from a pension fund, Rev. Rul. 76-385 has no effect. Likewise, if a corporation buys back more than 20% of a shareholder’s holdings, that is a safe harbor reduction, and the ruling does not matter. Most corporations could easily find enough tax-indifferent sellers to conduct their buybacks in a tax-efficient way, even without the protection of the ruling.