Corporate governance mitigates agency costs by protecting outside investors from exploitation from insiders, as well as aligning the financial and other incentives of insiders with those of the principal. The literature remains underdeveloped, however, on those tasked with shaping and enforcing internal corporate governance. These executives, known as gatekeepers, serve as reputational intermediaries who verify and certify information to the market. The most prominent gatekeeper in the firm is the Chief Legal Officer (CLO). The CLO is responsible for monitoring for firm misconduct, supervising internal and external legal resources, and advising the CEO and the board of directors on matters of compliance.

In spite of this gatekeeper role, the CLO is also expected to serve the role of facilitator. As a facilitator, the CLO participates as a member of the management team and serves the firm with the same interests and goals as fellow executives. CLO compensation may reinforce the facilitation role, granting performance-sensitive compensation to reward increases in firm value. As a result, CLO may discount her gatekeeping function in order to align her incentives with the CEO and CFO. This alignment by the CLO toward management may reduce barriers to management misconduct and inhibit the monitoring function valued by investors.

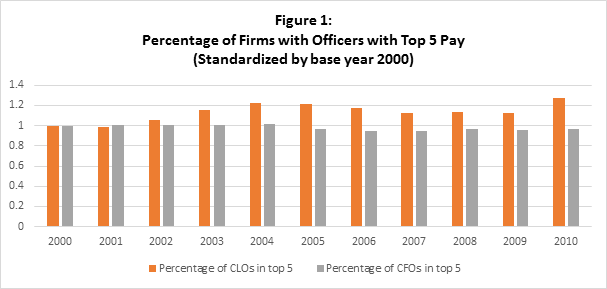

This results in a paradox for executive lawyers whereby CLOs, and by extension their legal staff, are forced to serve both as legal guardians that improve corporate governance and as corporate executives that augment firm value. CLOs that aggressively engage in their monitoring function may fulfill their gatekeeper role, but isolate themselves from the networks of top management with whom a collaborative relationship is necessary to function. Those that prioritize their executive role may harmonize easily with management, but allow corporate governance to degrade and suffer a loss of reputational capital when misconduct becomes public. Such attorneys may devalue the integrity of the justice system of which they serve and even be implicated in corporate misconduct of their own. The sanction of CLOs for such misconduct may be greater than their C-suite equivalents, because the CLO is subjected to strong bonding costs arising from their obligations to their profession and the judicial system. The CLO has been rising in prominence, with progressively more of them making it into the top five C-suite members in our sample, as shown in Fig. 1.

Our results find empirical support for the beneficial role of the CLO in the corporate governance of the firm. We also use the CFO as a comparator. First, we test whether board of director composition after a securities class action (SCA) lawsuit has been filed impacts CLO standing. Controlling for composition of the board of directors, the filing of a SCA increases the standing of the CLO, while the CFO’s value remains stagnant. This provides further evidence of the CLO’s value in a monitoring role. However, when the preceding year has a high Tobin’s Q, a measure of estimating the fair value of the stock market, the CLO’s relative compensation declines compared to other top five executives. Insiders may exploit high Tobin’s Q conditions for personal gain, and deemphasize the CLO in order to marginalize the monitoring function.

We also examine whether firm opacity impacts CLO standing. High opacity environments do not significantly impact CFO compensation. High opacity environments, however, are associated with higher relative compensation for the CLO. This may be evidence of the CLO’s value as a monitor when the ability of principals to do such monitoring is compromised. This higher relative compensation erodes somewhat for the CLO in high Tobin’s Q environments, which may be based on reduced shareholder and executive interest in monitoring governance because of strong firm performance.

Turnover results also speak to the role of the CLO. In the years after the firm is sued by a SCA, CEO and CFO turnover increase by 2 and 1.5 times respectively. As expected, a lawsuit may trigger the departure of the CFO and CEO who are punished for their substandard conduct. Turnover rates, however, do not change for the CLO when a SCA is filed. The CLO is not evaluated for her ex ante behavior as much as for her ex post ability to defend against the misconduct of management. We also find that CLO turnover does not impact the turnover rates of other executives, unlike CEO and CFO turnover which does. This presents contradicting evidence against the notion that a CLO withdrawal can imply misconduct which impacts the firm.

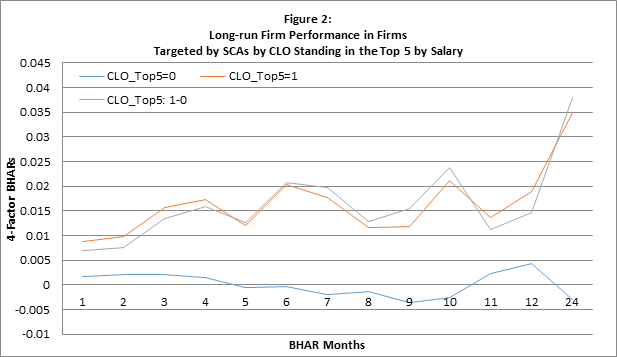

Given the importance of the CLO’s role in corporate governance, it becomes important to further examine to what extent the CLO can alleviate pressing principal agent problems in the firm. We find some evidence of the CLO’s value to the firm in terms of long-run abnormal performance as shown in Fig. 2:

Specifically, we find that firms that are targeted by SCAs, indicative of principal-agent problems, perform much better when there is a highly-paid CLO, indicative of a commitment to addressing these problems.[1] Thus, the CLO has clear value to the firm in the context of agency issues.

It is also necessary to further examine to what extent and under what conditions the CLO is vulnerable to problematic principal–agent behavior. Further research could examine to what extent legal standards and other professional bonding costs restrain the CLO from rent seeking behavior. In addition, further work can explore whether CLOs are subject to the managerial power hypothesis. If the managerial power effect has the ability to impact the CLO’s monitoring role, it increases support for the call for reforms. One such reform is that the CLO should be under the supervision and control of independent directors or someone other than senior management, and in particular the CEO. This would arguably better preserve the general counsel’s monitoring functions and shield counsel from undue influence, but could also undermine trust and confidence that builds between members of the senior management team. Further research is necessary to illuminate whether and under what circumstances the facilitator-monitor paradox of CLOs impacts governance and other practices of the firm.

ENDNOTES

[1] We benchmark performance using the standard four-factor model including the Fama and French (1993) factors plus the momentum factor as in Carhart (1997).

REFERENCES

Carhart, M. M. (1997). “On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance”. The Journal of Finance 52

Fama, E. F., French, K. R. (1993). “Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds”. Journal of Financial Economics 33

The preceding post comes to us from Robert Bird, Associate Professor at the University of Connecticut School of Business, Paul Borochin, an Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of Connecticut School of Business, and John D. Knopf, an Associate Professor of Finance at the University of Connecticut School of Business. The post is based on their article, which is entitled “The Role of the Chief Legal Officer in Corporate Governance”, was published in the Journal of Corporate Finance and is available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog

You guys are on to something. Tom Russo, CLO of Lehman Brothers, extracted well over $100 million in cash during his 14 year tenure there. (He’s doubled that since then as CLO of AIG.) The Lehman results speak for themselves. Keep up the good work.