While all acquisitions require approval from target shareholders, the necessary level of shareholder support varies across jurisdictions and deal structures. Some transactions can be approved by a simple majority of target shareholders, while others require super-majority approval. In our paper, Shareholder Decision Rights in Acquisitions: Evidence from Tender Offers, we investigate the impact of such variation on deal outcomes, particularly on the choice between a tender offer and merger structure.

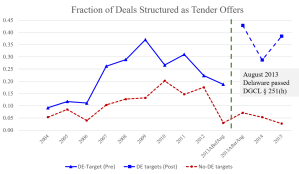

To isolate variation in approval thresholds, we use the 2013 enactment of Delaware General Corporation Law § 251(h), which reduced the shareholder support threshold to close out a two-step tender offer from 90 percent to 50 percent, but only for acquisitions of a target firm incorporated in Delaware. We show that removing the supermajority threshold significantly increases the use of tender offers for Delaware targets. Though the new law reduces target shareholders’ ability to vote on certain deals, they do not appear to be harmed by the change. Indeed, acquisition premiums and target cumulative abnormal returns are higher for Delaware targets acquired after passage of DGCL § 251(h) relative to target firms incorporated in other states.

Background

Bidders have two ways to acquire a target firm: long-form merger or two-step tender offer. Long-form mergers involve sending out a proxy statement and soliciting shareholder votes to approve the merger. Typically, approval from a simple majority of shareholders (i.e. 50 percent) is sufficient to effectuate the deal and gain full ownership. In contrast, two-step tender offers involve making an offer to purchase shares directly from target shareholders. Upon completion of the tender offer, the bidder will use either a long-form or short-form merger to acquire any remaining untendered shares. The short-form merger is the preferred route as it does not require a shareholder vote or proxy statement filing and can thus be completed significantly faster. Yet, short-form mergers historically required the bidder to own 90 percent of the outstanding shares compared with only 50 percent for a long-form merger. DGCL 251(h) removed the 90 percent barrier, but only for acquisitions of target firms incorporated in Delaware.

We consider two hypotheses. The first – Managerial Self-Dealing – suggests that a lower authorization threshold could increase the scope for self-dealing by senior management in tender offer acquisitions. Shareholder approval, especially by supermajority, can serve as a check against agency conflicts during merger negotiations. For example, shareholders can use their veto threat to prevent managers from bargaining over private benefits – such as bonuses or retention – at the expense of shareholder premiums. Thus, changing the authorization thresholds from 90 percent to 50 percent could result in lower acquisition premiums and increased use of side-payments to target executives.

The second hypothesis – Shareholder Hold-up – posits that lowering the authorization threshold could collectively benefit target shareholders by reducing the risk that a minority of shareholders will hold up a beneficial tender offer. The hold-up problem can arise for a variety of reasons. First, shareholders might lack information or possess heterogeneous beliefs about firm value. Second, the impact of a proposed transaction on an investor’s portfolio could cause some shareholders to vote against a deal, regardless of the payout to shareholders of the target firm. Third, a block-holder might strategically withhold support to secure its right to judicial appraisal. Regardless of the exact reason, the risk of hold-up is heightened for deals that require supermajority approval. This hypothesis predicts that the reduced authorization requirements brought about by 251(h) cause a substitution from long-form mergers to two-step tender offers because targets and bidders are now able to choose the more efficient structure, rather than being forced into a merger due to potential hold-up problems with a tender offer. Furthermore, as authorization thresholds are relaxed, tender offers become feasible for deals with a smaller surplus, and consequently premiums for tender offers and mergers should begin to converge.

Results

To test these predictions, we put together a sample of acquisitions of publicly-held U.S. targets announced from 2010 to 2015. We find a significant increase in the use of tender offers for Delaware targets following the passage of the new law. This effect is pronounced when compared with the infrequent use of tender offers outside Delaware over the same period. Based on our analysis, the predicted probability of a tender offer significantly increases from 29 percent to 40 percent for Delaware targets after August 2013, and decreases from 30 percent to 24 percent for non-Delaware targets. This result is illustrated in the graph below:

Even though DGCL § 251(h) lessens shareholders’ voting power, shareholders appear to benefit from the change. After passage of the new law, acquisition premiums and target cumulative abnormal returns are significantly higher and deal completion times significantly faster for Delaware targets relative to comparable targets from other states. We also find that bidders’ cumulative abnormal returns are significantly higher when acquiring a Delaware corporation. The fact that both groups of shareholders appear to benefit from the new law suggests that lowering the threat of shareholder holdup enables the parties to choose a more efficient deal structure. The increased use of tender offers particularly applies to deals involving high-volatility Delaware targets. This correlation between volatility and tender offers suggests that curtailing the option value of appraisal could benefit non-dissenting shareholders. This finding is consistent with the notion that potential disagreements over value could have made it especially difficult to obtain supermajority approval prior to the passage DGCL 251(h).

By contrast, we find no evidence of managerial self-dealing. In particular, the new law seems to have no effect on the likelihood that a target CEO will be retained or receive a merger side-payment.

This post comes to us from Professor Audra Boone at Texas Christian University, Professor Brian Broughman at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, and Professor Antonio Macias at Baylor University. It is based on their recent paper, “Shareholder Decision Rights in Acquisitions: Evidence from Tender Offers,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog