The process of determining whether big mergers comply with antitrust laws is careful and intensive. The Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice reported that in 2011 they examined in detail 40 percent, and initiated second request investigations in 15 percent, of all deals over $1 billion.[1] For example, after an extensive investigation that year, the Department of Justice blocked AT&T’s $39 billion acquisition of T-Mobile USA. AT&T had to pay a $4 billion reverse break fee, and its stock price dropped significantly.

The case shows how costly the antitrust review process can be for merging firms. Some of those costs are direct: filing charges, legal expenses, and, when deals fail, breakup fees. Other costs are indirect and harder to quantify: the delay and uncertainty of a lengthy review process during which deal financing must be kept in place and anxious employees and customers reassured.

In a recent paper, we empirically evaluate the costs of antitrust review for large public deals in the U.S. and investigate how acquirers manage those costs and risks through lobbying. Lobbying is a primary way for firms to communicate with legislators and regulators. We hand collected data regarding the antitrust review process from corporate filings, press releases, and agency reports for public M&A deals valued at over $100 million during the period from 2008 to 2014 and complemented it with corporate lobbying data from the Center for Responsible Politics and the Senate Office of Public Records. Our main results are three-fold.

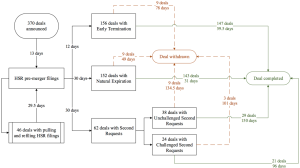

First, our rich description of the antitrust review process shows the timing of each step in the process and the distribution of outcomes. Merging firms make pre-merger filings with the antitrust agencies on average13 days after publicly announcing the deal, triggering a 30-day waiting period (see Figure 1). In 42.2 percent of deals, the agencies grant clearance 12 days after the pre-merger filing and terminate the waiting period earlier (Early Termination). Another 41.1 percent of deals are cleared upon expiration of the 30-day waiting period without receiving any adverse notifications (Natural Expiration). An adverse outcome occurs in 16.7 percent of deals, with one of the agencies initiating an in-depth antitrust investigation and requesting extensive additional information (Second Request). Only 38.7 percent of Second Requests result in an official complaint challenging the merger (Challenged Second Requests), while 61.3 percent of Second Requests are cleared.

Figure 1 The U.S. antitrust review process (median days between individual nodes).

A Second Request is costly. Deals qualifying as Early Terminations or Natural Expirations take 41 days on average after the waiting period to complete, while deals that are Second Requests take 171.5 days. Controlling for deal characteristics, we find that Second Requests double the total number of days from public announcement to deal completion or withdrawal. The extended time to completion increases other risks and leads to acquirers more often being unable to protect against bidding competition, financing uncertainty, or industry changes that can make a deal impractical. Second Requests are associated with a five percentage point increase in withdrawal rate. What’s more, investors closely watch the antitrust review process. A Second Request raises costs and risk and so its announcement is associated with a significant –2.8 percent abnormal return on the acquirer’s shares, while Early Terminations and Natural Expirations have only an insignificant effect on those shares. The negative market reaction for Second Requests is more pronounced for deals with major anti-competitive concerns.

As a second step, we explore acquirer lobbying before and after merger announcements and their link with antitrust review outcomes. Our results suggest that acquirers lobby more to improve the chances of a favorable outcome. The annual acquirer lobbying expenditure amounts on average to $3 million, or .015 percent of their average market capitalization. Pre-announcement lobbying aims at avoiding Challenged Second Requests. Moreover, acquirers step up their lobbying in the post-announcement period when they are likely to end up with a Challenged Second Request. Additional analysis shows that acquirers particularly benefit from long-term and persistent lobbying rather than ad-hoc lobbying triggered by adverse review outcomes.

Notably, we observe a group of firms strategically pulling and refiling their pre-merger filings to extend the statutory waiting period and to provide more time for antitrust agencies to conduct reviews without immediately triggering a Second Request. We define deals that clear antitrust review after one or more pulling-and-refiling attempts as “Pull&Refiles.” They represent 8.4 percent of deals in our sample. Our analysis shows that Pull&Refiles are associated with more acquirer lobbying, especially in the post-announcement period, and suggests that lobbying is designed to avoid an adverse Second Request.

In the last part of our analysis, we explore how lobbying affects the value of acquirers’ stock. We show that the market reacts more positively to deals where the aquirer has done more pre-announcement lobbying. More lobbying is also positively correlated with the expected completion probability as reflected in a smaller gap between the target stock price just after the deal announcement and the initial offer price. Moreover, lobbying is valued more for deals with higher anti-competitive concerns. In contrast, the market does not consider lobbying positively in poorly governed firms with entrenched managers who may undertake value-destroying acquisitions.

In summary, our paper documents substantial regulatory costs and risks in M&A and provides evidence that firms actively manage these costs and risks through their lobbying activities. On the whole, our results underline the importance of political connections for corporate investment when facing high regulatory costs and risks.

ENDNOTE

[1] See the 2011 Hart-Scott-Rodino Annual Report at https://www.ftc.gov/reports/34th-report-fy2011.

This post comes to us from Jana P. Fidrmuc, an associate professor at Warwick Business School, Peter Roosenboom, a professor at Erasmus University, and Eden Quxian Zhang, a lecturer at Monash University. It is based on their recent paper, “Antitrust merger review costs and acquirer lobbying,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog