While the list of prospective issuers with credit ratings is lengthy, literature is sparse on how ratings from multiple credit rating agencies (CRAs) affect the performance of a company’s initial public offering (IPO). Our research is motivated by the lack of such literature and by Sangiorgi and Spatt (2017), who argue that multiple ratings are socially optimal if the benefit of the additional rating outweighs the cost of information production. This argument aligns with the “shopping hypothesis” and “information production hypothesis” of Bongaerts et al. (2012). Under the former hypothesis, issuers “shop” for an additional rating in hopes of improving their rating, while under the latter hypothesis, investors are averse to uncertainty, which is reduced by additional ratings.

Based on the total number of IPOs on U.S. stock exchanges from January 1, 1997, to December 31, 2016, and ratings provided by the three leading U.S. CRAs – Fitch, Moody’s, and Standard & Poor’s, we find that the preferred CRA among issuers is S&P, followed by Moody’s and then Fitch. Also, descriptive statistics indicate that Moody’s rating criteria are stricter than S&P’s.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the only study to investigate multiple credit ratings as a means of signaling the quality of an upcoming equity offering. We find that multiple credit ratings reduce the IPO underpricing and the magnitude of the revision of the filing price more than single ratings do. Economically, this translates into an average increase in IPO proceeds of $17.47 million for the average-sized IPO firm.

To explore how the ratings affect IPO underpricing, we review the impact of their levels on the IPO’s initial returns. We find that, while the level of the rating for single-rated firms does not matter, it does for multi-rated firms. Moreover, we consider whether companies with ratings between BB and BBB — on the borderline between investment and non-investment grade — seek to obtain more than one rating. Our findings suggest that 83 percent of such companies do, suggesting that they are more likely to seek multiple credit ratings to improve their creditworthiness.

Further, we provide new evidence about the impact of credit rating dispersion on IPO underpricing by using the difference between each firm’s second and first rating as a measure of credit analysts’ optimism or pessimism. In particular, optimism (pessimism) corresponds to a stronger (weaker) second rating. We find a negative (positive) and highly significant association between credit analyst optimism (pessimism) and underpricing. In other words, the greater the analyst’s optimism (pessimism) the lower (higher) the IPO underpricing. Moreover, our findings show that firms with a higher second rating experience an average increase in their IPO proceeds of $18.50 million.

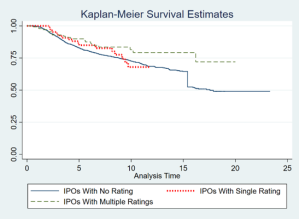

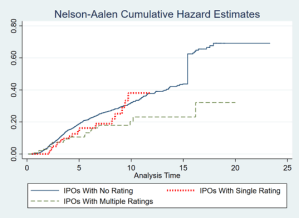

IPOs are known for their underperformance in the long run, with a large proportion of issuers failing to survive during the first three years. That may affect CRAs’ confidence in their ratings and how they rate firms with high leverage but a relatively short history of published financial statements. Hence, we explore the likelihood of survival (default) for companies that decide to go public with multiple credit ratings and compare it with companies with either a single rating or no rating.

Survival analysis is an econometric technique used extensively in the literature examining the determinants of IPO firm survival. The survival function projects the probability that a firm survives a specified period of time. For example, if multiple ratings increase the survival rate of an issuing firm, then the curve of the survival function for multi-rated companies will be above the curve of firms with either no rating or just one.

Figure 1 shows that the survival function five years after the IPO for firms with multiple ratings exceeds the equivalent function for firms with no rating or a single rating. Time widens the gap between the three types of firm. Figure 2 shows that, two years after the IPO, the curve for the multi-rated firms is below the curves for the firms with a single or no credit rating, and the corresponding vertical distance between the curves increases substantially over time. These results show that firms with multiple ratings are more likely to survive and less likely to default.

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier Survival Estimates

Figure 2. Nelson–Aalen Cumulative Hazard Estimates

Our study makes an important contribution to the debate about the value of obtaining multiple credit ratings. It suggests that multiple credit ratings (and their levels) reduce IPO underpricing and the price revisions. Moreover, we offer new insights into the survival of firms that engage in IPOs, arguing that companies with multiple ratings have a higher chance of survival.

REFERENCES

Bongaerts, D., Cremers, K.M. and Goetzmann, W.N., 2012. Tiebreaker: Certification and multiple credit ratings. The Journal of Finance, 67(1), pp.113-152.

Griffin, P.A., Hong, H.A., Ryou, J.W., 2018. Corporate innovative efficiency: Evidence of effects on credit ratings. Journal of Corporate Finance, 51, pp.352-373.

Sangiorgi, F. and Spatt, C., 2017. Opacity, credit rating shopping, and bias. Management Science, 63(12), pp.4016-4036.

This paper comes to us from professors Marc Goergen at IE Business School and the European Corporate Governance Institute, Dimitrios Gounopoulos at the University of Bath, and Panagiotis Koutroumpis at Queen Mary University London and City University London. It is based on their recent paper, “Do Multiple Credit Ratings Reduce Money Left on the Table? Evidence from U.S. IPOs,” available here.

Sky Blog

Sky Blog